A recognized need. “Freedom is a conscious necessity. Helpful to repeat questions

"FREEDOM IS A CONSCIOUS NECESSITY" - where did this strange slogan come from? Who first came up with the idea of identifying freedom with necessity, even if "conscious"?

Some say it was Spinoza. For example, the anonymous author of the article "Freedom and Necessity" in the "Philosophical Dictionary" of 1963 confidently states: "The scientific explanation of S. and N. is based on the recognition of their organic relationship. The first attempt to substantiate this t. defined S. as conscious N." However, in order to make such statements, one must at least not read Spinoza. For Spinoza, "TRUE FREEDOM CONSISTS ONLY IN THAT THE FIRST CAUSE [of ACTION] IS NOT INCLUDED OR OBSTRUCTED BY ANYTHING ELSE, and only through its perfection is the cause of all perfection." Such freedom, according to Spinoza, is available only to God. He defines human freedom as follows: "it is a STRONG EXISTENCE, WHICH OUR MIND GET THANKS TO THE DIRECT CONNECTION WITH GOD, in order to cause in itself ideas, and outside of itself actions, consistent with His nature; and His actions should not be subordinated to any external reasons that could change or transform them" ("On God, Man and His Happiness", translated by A.I. Rubin). Well, where is the "realized N."?

Some attribute the "realized necessity" to Engels. For example, Joseph Stalin, in his talk about the textbook "Political Economy" (1941), speaks of this as a matter of course: "Engels wrote in Anti-Dühring about the transition from necessity to freedom, wrote about freedom as a CONSCIOUS NECESSITY." He must not have read Engels, since the cited work literally says the following:

"Hegel was the first to correctly present the relationship between freedom and necessity. For him, FREEDOM IS THE KNOWLEDGE OF NECESSITY. "Necessity is blind only because it is not understood." Freedom does not lie in an imaginary independence from the laws of nature, but in the knowledge of these laws and in the possibility based on this knowledge to systematically force the laws of nature to work for certain purposes.

("Hegel war der erste, der das Verhältnis von Freiheit und Notwendigkeit richtig darstellte. Für ihn ist die FREIHEIT DIE EINSICHT IN DIE NOTWENDIGKEIT. "Blind ist die Notwendigkeit nur, insofern dieselbe nicht begriffen wird". liegt die Freiheit, sondern in der Erkenntnis dieser Gesetze, und in der damit gegebnen Möglichkeit, sie planmäßig zu bestimmten Zwecken wirken zu lassen".)

Hegel, however, never once called freedom "KNOWLEDGE OF NECESSITY". He wrote that "freedom, being embodied in the reality of a certain world, takes the form of necessity" (die Freiheit, zur Wirklichkeit einer Welt gestaltet, erhält die Form von Notwendigkeit), and more than once called freedom "die Wahrheit der Notwendigkeit" ("TRUTH NECESSARY"), whatever that means. And in his works there are at least a dozen different definitions of freedom - but it is precisely Engels' formulation that is not there.

Here, perhaps, it would be necessary to explain what "necessity" Hegel had in mind. It has nothing to do with "essentials". The notwendigkeit he is talking about is when subsequent facts "necessarily" follow from previous ones. Simply put, "inevitability" or "conditionality." Or even "karma" as some people put it. Well, Freiheit in this context is not "the absence of obstacles to movement", but free will. In other words, Hegel is trying to prove that the conscious will of man makes the possible inevitable - well, or something like that. It is not easy to understand him even in German, and one can draw any conclusions from his vague speeches.

Engels, as we have already seen, understood in his own way. He turned the abstract "truth" into a more concrete "understanding", tied it to the scientific worldview, signed it with the name of Hegel and passed it on. And then there were Russian Marxists with their specific understanding of everything in the world.

To LENIN's credit, it should be noted that he did not misrepresent Engels. The corresponding passage from "Anti-Dühring" in his work "Materialism and Empirio-Criticism" is translated quite correctly:

"In particular, it should be noted Marx's view on the relation of freedom to necessity: "necessity is blind until it is recognized. Freedom is the CONSCIOUSNESS OF NECESSITY" (Engels in "Anti-Dühring") = recognition of the objective regularity of nature and the dialectical transformation of necessity into freedom (along with the transformation of the unknown, but cognizable, "thing in itself" into "a thing for us", "the essence of things" into "phenomena").

Einsicht, in principle, can be translated both as "knowledge", and as "awareness", and even as "familiarization" - there are many options. But there are nuances. "Consciousness" in Russian is not just "acquaintance with something", but also "subjective experience of the events of the external world." In other words, "knowing" the need, we just get information about it; and "realizing" the need - we also experience it subjectively. We usually KNOW the world, ourselves and other interesting things, but we KNOW our duty, our guilt and other negative things - this is how Russian word usage works.

Was Vladimir Ilyich aware of this? I do not undertake to guess, but one thing is certain: it was not he, not Marx, not Engels, not Hegel, and certainly not Spinoza, who identified freedom with necessity. Spinoza, as you remember, called freedom "solid existence", Hegel - "truth", Engels - "knowledge", Lenin - "consciousness". Well, Marx has nothing to do with it.

So where did she come from, this "realized need"? It's funny to say - but it seems that it itself arose from Lenin's formulation in the minds of people who knew Russian not so well as to feel the difference between a verbal noun and a participle. There were many such authors among the early theorists of Marxism-Leninism, their creations are innumerable, and now go and figure out which of them was the first to blind this oxymoron and how consciously he did it. But now, it stuck and almost became a slogan. This is how it happens, yes.

UPD 05/11/2016: The author of the "realized need" was finally found! It was Plekhanov. Here is a quote: “Simmel says that freedom is always freedom from something, and that where freedom is not thought of as the opposite of bondage, it has no meaning. It is, of course, so. But on the basis of this little elementary truth, it is impossible to refute the proposition, which is one of the most brilliant discoveries ever made by philosophical thought, that freedom is a conscious necessity».

[Plekhanov G.V. On the question of the role of personality in history / Selected philosophical works in five volumes. T. 2. - M .: State Publishing House of Political Literature, 1956. S. 307]

Many thanks to LiveJournal user sanin who made this amazing discovery!

If chance determines the diversity of possibilities, and necessity determines their uniformity, then freedom is the unity of possibilities in their diversity, or the diversity of possibilities in their unity.

Contrasting views on freedom

In the history of philosophy, one can observe two mutually exclusive points of view on the concept of freedom.

Some philosophers (for example, Spinoza, Holbach, Kant, Schelling, Hegel) bring the concept of freedom closer to the concept of necessity; they either deny the presence of an element of chance in freedom, or downplay its importance. Here is how B. Spinoza characterized freedom:

“Freedom is such a thing that exists only by the necessity of its own nature and is determined to act only by itself ...” The famous formula comes from Spinoza: “Freedom is the knowledge of necessity” (it sounds like this: freedom is knowledge “with the eternal necessity of oneself, God and things” [Ethics, Vol. 42]).

Hegel interpreted this formula in his own way. Then in Marxism it was the main one in defining the concept of freedom.

This point of view received its extreme expression in Holbach. "For man," he wrote, "freedom is nothing but a necessity contained in him." Moreover, Holbach believed that a person cannot be truly free, since he is subject to the action of laws and, therefore, is in the grip of an inexorable necessity.

The feeling of freedom, he wrote, is “an illusion that can be compared with the illusion of a fly from a fable that imagines, sitting on the drawbar of a heavy cart, that it controls the movement of the world machine, but in fact it is this machine that draws a person into the circle of its movement without him. known."

Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason put forward an antinomy: there is freedom in man, there is no freedom at all. In the world of appearances, according to Kant, necessity dominates; in the world of things in themselves, man is free. But what, according to Kant, is freedom? - A.A. Gulyga asks a question. And he answers in Kantian: “This is the following of moral duty, that is, again, the subordination of man to necessity. The challenge is to choose the right need.” In the book dedicated to Kant, A.A. Gulyga explains his position as follows:

“Freedom from the point of view of ethics is not arbitrariness. Not just a logical construction, in which different actions can equally follow from a given cause. I want - I will do so, but I want - quite the opposite. The moral freedom of the individual consists in the realization and fulfillment of duty. Before oneself and other people, “free will and will subject to moral laws are one and the same.”

Schelling's position is in many ways similar to that of Kant. “A person is evil or good,” writes A.A. Gulyga, setting out Schelling’s position, “it’s not by chance, his free will is predetermined. Judas betrayed Christ voluntarily, but he could not do otherwise. A person behaves according to his character, and character is not chosen. You can't escape fate! Schelling calls the doctrine of freedom of choice "moral plague". Morality cannot rest on such a shaky foundation as personal desire or decision. The basis of morality is the awareness of the inevitability of certain behavior. "That's where I stand and I can't do otherwise." In the words of Luther, who realized himself as the bearer of fate, there is an example of moral consciousness. True freedom consists in conformity with necessity. Freedom and necessity exist one within the other. Elsewhere, A.A. Gulyga describes Schelling’s position in the following way: “The process of creation is the self-limitation of God. (“The master manifests himself in the ability to limit himself,” Goethe quotes Schelling) This happens by the free will of God. Does this mean that the world arose by chance? No, it does not mean: absolute freedom is an absolute necessity, there can be no question of any choice with free expression of will. The problem of choice arises where there is doubt, where the will is not clear, and therefore not free. Who knows what he needs, acts without choosing. In the System of Transcendental Idealism, Schelling, speaking about the movement of society towards a global civil order, spoke of the interweaving of the free activity of people with historical necessity (as both Hegel, K. Marx and F. Engels later said):

“Although a person is free in relation to his immediate actions, the result to which they lead within the limits of visibility depends on the necessity that stands above the actor and participates even in the deployment of his very freedom.”

A. Gulyga comments:

“We act completely freely, with full consciousness, but as a result, something arises in the form of the unconscious that has never been in our thoughts. Hegel would call such a combination "cunning of the mind"

In On the Method of University Education, Schelling speaks of the importance of necessity in history:

“In history, as in drama, events follow necessarily from the previous and are comprehended not empirically, but thanks to the higher order of things. Empirical reasons satisfy reason, but for reason history exists only when the tools and means of higher necessity appear in it.

He also argued that in a perfect state, necessity merges with freedom.

And here is Hegel's opinion on freedom and necessity:

“...but true, the spirit is concrete, and its definitions are both freedom and necessity. Thus, the highest understanding is that the spirit is free in its necessity and only in it finds its freedom, just as, conversely, its necessity is based only on its freedom. Only here it is more difficult for us to assume unity than in the objects of nature. But freedom can also be abstract freedom without necessity; this false freedom is arbitrariness, and for this very reason it is the opposite of itself, unconscious bondage, an empty opinion about freedom, formal freedom.

Other philosophers, on the contrary, oppose the concept of freedom to the concept of necessity and thereby bring it closer to the concept of chance, arbitrariness.

The American philosopher Herbert J. Muller writes, for example:

“To put it simply, a man is free insofar as he can take up or refuse a business at will, make his own decisions, answer “yes” or “no” to any question or order, and, guided by his own understanding, determine the concepts of duty and worthy He is not free insofar as he is deprived of the opportunity to follow his inclinations, but due to direct coercion or fear of consequences, he is obliged to act contrary to his own desires, and it does not matter whether these desires benefit him or harm him.

A similar understanding of freedom (according to the principle "I do what I want") can be found both in the German philosophical dictionary and in the Concise Philosophical Encyclopedia. Hegel rightly remarked on this matter: "When we hear that freedom consists in the ability to do whatever one wants, we can recognize such a notion as a complete lack of culture of thought."

And here is a witty remark from a collection of prison aphorisms: do what you want, but so as not to lose this opportunity in the future.

It is very difficult, of course, to realize the presence in freedom of both moments: chance and necessity. The rational thought beats in a vice "or". In Marxist philosophy, in spite of the fact that everyone considered themselves dialecticians, there was some accidental fear in assessing and characterizing freedom. Here is what I. V. Bychko wrote, for example:

"" The existence of chance, - says one of the leading representatives of American naturalism C. Lamont, - gives rise to freedom of choice, although it does not guarantee that it will actually come true "(C. Lamont. Freedom of Choice Affirmed. N.Y. 1967, p. 62). Having identified (or at least brought too close) freedom to chance, Lamont, on this basis - quite in the spirit of eighteenth-century materialism - contrasts freedom with determinism.

The above quotation from the work of K. Lamont does not contain what I. V. Bychko ascribes to it. The thought contained in it is quite fair. Paradoxical as it may seem, freedom necessarily presupposes chance, is impossible without it. Even Aristotle noted that the denial of the real existence of chance entails the denial of the possibility of choice in practical activity, which is absurd.

“The destruction of chance,” he wrote, “entails absurd consequences ... If there is no chance in phenomena, and everything exists and arises out of necessity, then there would be no need to consult or act in order to, if we do so, it would be one thing, and if otherwise, then this was not.

Some of our philosophers literally "fixed" on the formula "freedom is a recognized necessity." Meanwhile, Hegel himself, if we take in the aggregate all his statements about freedom, did not understand this category in such a simplified way. He essentially recognized that freedom contains in a sublated form both moments: chance and necessity, and not just one necessity. So in the Minor Logic, he speaks of bare arbitrariness as will in the form of chance. On the other hand, he does not deny that a truly free will in a sublated form contains arbitrariness (the will "contains in itself the random in the form of arbitrariness, but contains it in itself only as a sublated moment"). Elsewhere in the Minor Logic, he wrote that "the true and reasonable concept of freedom contains in itself necessity as sublated." Thus, the view attributed to Hegel that freedom is a recognized necessity is only a half-truth, which distorts the complex and multifaceted idea of the German thinker about freedom.

The fate of this philosopher is full of drama, and his name has become a kind of symbol of logic and rationality in European philosophy. Benedict Spinoza (1632-1677) considered the vision of things to be the highest goal of this science. in terms of eternity. And on his seal for letters was a rose with the inscription at the top: "Caute" - "Cautiously."

Benedict Spinoza (Baruch d'Espinoza) was born in Amsterdam into a wealthy family of Spanish Jews who fled to Holland from persecution by the Inquisition. Although they were forced to convert to Christianity, they secretly remained faithful to Judaism. At first, Spinoza studied at the school of the Jewish community in Amsterdam, where he learned the Hebrew language, deeply studied the Bible and the Talmud.

After that, he moved to a Christian school, where he mastered Latin and the sciences - he discovered the ancient world, the culture of the Renaissance and new trends in philosophy created by R. Descartes and F. Bacon. Gradually, the young Spinoza became more and more distant from the interests of his community, so that he soon entered into a serious conflict with it.

The deep mind, talents and education of the young man were evident to everyone, and many members of the community wanted Spinoza to become their rabbi. But Spinoza refused in such a sharp form that some fanatic even attempted on the life of the future great rationalist - Spinoza was saved only by the fact that he managed to dodge in time, and the dagger cut through only his cloak. So already in his youth, Spinoza was forced to defend his freedom, the right to his own choice. In 1656 he was expelled from the community, and his sister disputed his right to the inheritance. Spinoza sued and won the process, but did not accept the inheritance itself - it was important for him to prove only his rights. He moved to the vicinity of Amsterdam and there, living alone, took up philosophy.

From 1670 Spinoza settled in The Hague. He learned to grind glass and earned his living by this craft, although by this time he was already known as an interesting deep philosopher. In 1673, he was even offered to take the chair of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg, but Spinoza refused, because he feared that in this position he would have to make worldview compromises, because, having abandoned Judaism, he never accepted Christianity. He lived alone and very modestly, although he had many friends and admirers of his philosophy. One of them even gave him money for life maintenance - Spinoza accepted the gift, but at the same time asked to significantly reduce the amount. Benedict Spinoza died at the age of 44 from tuberculosis.

Spinoza's main philosophical work was his "Ethics". He always considered himself a follower of the rational philosophy of Descartes and his "geometric" method of cognition, which involves rigorous proofs of any statement. In the "Ethics" Spinoza brought the method of his teacher to the logical limit - this book in the manner of presentation resembles rather a textbook on geometry. First, there are definitions (definitions) of the main concepts and terms. Then follow obvious, intuitively clear ideas that do not require proof (axioms). And, finally, statements (theorems) are formulated, which are proved on the basis of definitions and axioms. True, Spinoza was nevertheless aware that philosophy would hardly be able to fully fit into such a strict framework, and therefore he provided the book with numerous comments, in which he set out the philosophical argument itself.

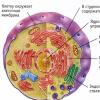

The main idea of Spinoza, on which his entire philosophy is "strung", is the idea of a single substance of the world - God. Spinoza proceeded from the Cartesian concept of substance: “Substance is it is a thing for the existence of which nothing else is needed, except for itself. But if the substance is the basis of itself, that is, it creates itself, then, Spinoza concluded, such a substance must be God. This is the "philosophical God", which is the universal cause of the world and is inextricably (immanently) associated with it. The world, Spinoza believed, is divided into two natures: creative nature and created nature. Substance, or God, belongs to the first, and modes to the second, i.e. single things, including people.

Since the world is permeated by a single substance, a strict necessity reigns in it, emanating from the substance itself, or God. Such a world, Spinoza believed, is perfect. But where does fear, evil, lack of freedom come from? Spinoza answered these questions in a very peculiar way. Yes, a person is drawn in life by a perfect necessity, but often the person himself does not understand this and he becomes afraid, a desire arises to contradict the need, and then passions take possession of his soul, he does evil. The only way out is to realize this need. Hence his famous "freedom formula": Freedom is a conscious necessity.

Spinoza defined human virtue in his own way. Since the world is perfect, it seeks to preserve itself. Therefore, Spinoza believed: "For us to act according to virtue means nothing more than to live, taking care of self-preservation, guided by reason and our own benefit." True, Spinoza himself, judging by his biography, did not really care about “self-preservation”, he was more attracted by the opportunity to think rationally, because this meant for him “bliss with the highest intellectual knowledge”, which is “not only a virtue, but also the only and highest reward for virtue." Virtue, Spinoza believed, carries a reward in itself, making "paradise" possible already here on earth.

This is how many philosophers interpreted freedom - B. Spinoza, G. Hegel, F. Engels. What is behind this formula, which has become almost an aphorism? There are forces in the world that act immutably, inevitably. These forces also influence human activity. If this necessity is not comprehended, not realized by a person, he is its slave; if it is known, then the person acquires "the ability to make a decision with knowledge of the matter." This is the expression of his free will.

But what are these forces, what is the nature of necessity? There are different answers to this question. Some see God's providence here. Everything is predestined for them. What then is the freedom of man? She is not. “The foresight and omnipotence of God are diametrically opposed to our free will. Everyone will be forced to accept the inevitable consequence: we do nothing of our own free will, but everything happens out of necessity. Thus, we do nothing of free will, but everything depends on the foreknowledge of God,” argued the religious reformer Luther. This position is advocated by the supporters of absolute predestination. In contrast to this view, other religious figures suggest the following interpretation of the relationship between Divine predestination and human freedom: “God designed the Universe so that all creation would have a great gift - freedom. Freedom first of all means the possibility of choosing between good and evil, moreover, a choice given independently, on the basis of one's own decision. Of course, God can destroy evil and death in an instant. But at the same time He would simultaneously deprive the world and freedom. The world itself must return to God, since it itself departed from Him.

The concept of "necessity" can have another meaning. Necessity, according to a number of philosophers, exists in nature and society in the form of objective, i.e., laws independent of human consciousness. In other words, necessity is an expression of a natural, objectively conditioned course of development of events. Supporters of this position, unlike fatalists, of course, do not believe that everything in the world, especially in public life, is rigidly and unambiguously determined, they do not deny the existence of accidents. But the general regular line of development, deviated by chance in one direction or another, will still make its way. Let's turn to examples. Earthquakes are known to occur periodically in seismically hazardous areas. People who do not know this circumstance or ignore it, building their homes in this area, may be victims of a dangerous element. In the same case, when this fact is taken into account in the construction of, for example, earthquake-resistant buildings, the probability of risk will sharply decrease.

In a generalized form, the presented position can be expressed in the words of F. Engels: “Freedom lies not in the imaginary independence from the laws of nature, but in the knowledge of these laws and in the possibility based on this knowledge to systematically force the laws of nature to act for certain goals.”

Thus, the interpretation of freedom as a recognized necessity presupposes the comprehension and consideration by a person of the objective limits of his activity, as well as the expansion of these limits due to the development of knowledge, the enrichment of experience.

The position of freedom as a recognized necessity is in a certain place - in Marxist philosophy. This dialectical (Hegelian) correlation of freedom and necessity, reworked in a materialistic vein, has become one of the basic concepts of Marxism, which is often presented as an aphorism.

Indeed, in terms of completeness and depth of thought, in terms of refinement and conciseness of form, the definition “freedom is a recognized necessity” fully corresponds to an aphorism. However, another undoubted feature of the aphorism, namely, the immutability of its verbal form, i.e. the text itself, turned out to be uncharacteristic for this provision. The knowledge of necessity is easily replaced by the awareness of necessity, as if they were absolute synonyms.

This observation is interesting: Yandex statistics show that the combination “recognized need” is requested about 166 times a month, while “recognized need” is 628 times, and the second request gives mixed results - “conscious” along with “recognized”. There is no mixed picture for the first query. Those. obviously, it was not the original text that turned out to be more popular, but the modified one, and the confusion in the second case shows that different combinations are more often presented as identical.

What are the reasons for the substitution is an interesting question, and the substitution itself is a significant question, since the opponents and critics of Marxism use exclusively the combination “conscious necessity”, interpreting the Marxist definition of freedom either as absurd or as immoral.

Of course, the words "know" and "realize", being of the same root, are related, but obviously not absolute synonyms. To know means to comprehend, to study, to gain knowledge, to experience. Realize - understand, accept, consciously assimilate. The difference is clearly visible in the examples. Any believer will confirm that he is aware of the greatness of God (without this there is no Faith), but it is impossible to know the greatness of God through religion. Awareness of oneself is an indispensable component of a person, personality. Self-knowledge is a process that can last a person's entire life, and not everyone is necessarily engaged in self-knowledge. We can be aware of some danger, fortunately never knowing it.

What is the need? Even without a detailed analysis, it is clear that necessity is a very broad concept. So, the need for water for life is one thing, the need for a passport for travel is another. The need to have a correct condition for solving a formal problem is one necessity, the need to help one's neighbor is a completely different one. It is impossible to reduce one to another need physical, normative, logical, ethical, linguistic. Not every need is recognized or known. At the same time, all the needs have something in common in the name itself: something that cannot be dispensed with - in different spheres, at different levels, in the objective world or in the subjective world of each individual person.

The same with freedom - free entry, free fall, free choice ... What do all freedoms have in common? Probably the general opposite of any freedom, and most agree that this is the very need.

Then the simplest definition would be: freedom is the absence of necessity. But… “I am free like a bird in the sky…” Does this mean that there is no need for a free bird in the sky? Let the beautiful, but narrow poetic image of freedom be forced to make room, if you put next to it the narrow, but quite specific meaning of this flight - it itself is dictated by some necessity. Animals generally do nothing without necessity, their whole life is subjection to a series of necessities. And then the animals have no freedom at all, although they don't realize it.

So we come to the conclusion that freedom as a category, a concept, as a state, as a possibility, is related only to a person - to a subject with consciousness. Necessity embraces the whole objective world, the whole reality, constituting in its various manifestations the conditions for the existence of all nature and society, as well as the individual person.

The connection between object and subject, matter and consciousness, objective and subjective reality, necessity and freedom is unlikely to be disputed by anyone. Differences begin on the question of the direction of this connection. A purely idealistic approach implies a direction away from the subject, away from consciousness, away from subjective reality, away from freedom. Vulgar-materialistic - a direction from the object, from matter, from objective reality, from necessity. And then freedom as will exists completely independently of necessity and is only limited by it, or freedom as will is inevitably and completely suppressed by necessity.

It seems surprising, but the definition of “freedom is a conscious necessity” is used not only to criticize Marxism from both sides (“how can freedom be unfreedom, and even conscious ?!”, “Marxism gives freedom to some to suppress the freedom of others and requires it to be realized”) but can easily be accepted by both parties. I have read the argument that anyone can become free by realizing the need, accepting it as inevitable, and this frees the choice created by the need. Or vice versa - the awareness of the need is a manifestation of the original freedom that a person is endowed with. Truly the definition of a chameleon ...

The definition "freedom is a recognized necessity" is inconvenient for turning this way or that. The dual relationship between freedom and necessity is fixed by knowledge, which is a process that constantly changes the relationship between freedom and necessity. The knowledge of necessity is the comprehension of the realities of the world, the acquisition of knowledge about the connections of this world and the study of their patterns. Knowledge is power, it gives tools to influence the need, to subordinate it to the will of man. Free action is action, in the words of Engels, "with knowledge of the matter." The degree of freedom is determined by the depth of knowledge - the deeper the knowledge of necessity, the greater the choice a person has for action.

Humanity in general and each person is born in the realm of necessity. The first knowledge means not only the acquisition of the initial degrees of freedom, but also strengthens the desire to expand this freedom, which drives knowledge. Moreover, an action performed under certain conditions of freedom of choice becomes an objective reality, it is woven into the general system of connections of the objective world, changing the necessity, i.e., in fact, creating it. This contradiction between freedom and necessity is resolved by the only way - by the constant deepening of the knowledge of necessity - a process that constantly expands freedom.

The philosophical dialectical-materialistic understanding of freedom denies the illusory nature of freedom that is not associated with the knowledge of necessity, and also reflects the relative nature of freedom. Freedom is not abstract, but always concrete. The actions performed in the presence of a certain choice are concrete, the consequences of these actions are concrete, the necessity transformed as a result, the knowledge of which is another free step to a new level of freedom, is concrete.

None of this is necessary in awareness, and there is no real freedom in awareness. There is only a departure from real necessity into the illusory freedom of awareness or conscious, and therefore free submission to necessity.

Two simple examples. How freely could we move through the air today if we realized, and did not know to a certain level, the obvious need to move exclusively on land or water? How free will a person be if a child from early childhood is not motivated to recognize the need, but is forced to realize it, which is easiest to do with the help of physical and / or psychological pressure?

The concept of freedom is especially important, complex and always relevant in relation to society, to the needs that arise in the course of its historical development. In more detail about this, as well as about the possible reasons for replacing “knowledge” with “realization” in the Marxist definition of freedom, it is probably worth and will have to be discussed separately.

Other related materials:

15 comments

your name 25.12.2016 20:29

Was Spartacus free in his struggle against the historically necessary slavery? When, before its downfall, there was nothing necessary, much less known? I can't imagine a freer person.

…

In order to prove that not all sheep are white, it is enough that there is only one black sheep. So that Freedom is not any kind of necessity - one free Spartacus is enough.

your name 25.12.2016 21:02

The concept of freedom, as it was presented by Marx, was certainly solved in the works of other philosophers of the Marxist trend of our century, and is not limited to the point of view of Tatyana Vasilyeva. I would like to see more serious materials, more serious philosophers and more serious analysis than excursions into the problem of raising children close to the author.

Tatyana 26.12.2016 05:06

Spartacus studied at the school of gladiators. His knowledge was enough for what he was able to achieve, and not enough to win. The slave uprisings were mostly spontaneous, and most of the slaves probably joined Spartacus spontaneously. But without his warriors, Spartacus would not be Spartacus. Spartacus, of course, had a greater degree of freedom than each of his warriors, because he became a leader and proved to be a good commander, because we know him.

Slave uprisings did not immediately, but changed the existing need, but that's another story.

your name 26.12.2016 06:16

I see that we got acquainted with the biography of Spartacus, It is easier than the concept of external and internal freedom in modern philosophy and the place of Marx in it.

your name 26.12.2016 09:09

Marxism is undeniably a science, but accessible to a few, and we need simple, understandable and accessible definitions for everyone. So the concept of Spartacus is more understandable and close to people than your wisdom about the wisest. Sorry for the sarcasm.

cat Leopold 26.12.2016 21:41

Tatyana, why did you give out such nonsense in the title ???

Who slipped you this STUNNING alternative between conscious and cognized necessity?

That which is UNKNOWN, CANNOT be KNOWN!

The subject of comprehension of something, and even more so of cognition, is ONLY HUMAN, because both RECOGNITION and cognition of something are accomplished in the PRACTICAL activity of people. Outside of this, there is NO and CANNOT BE either one or the other.

cat Leopold 26.12.2016 21:54

“Marxism is undeniably a science, but accessible to a few, and we need simple, understandable and accessible definitions for everyone.” - Your name.

Alas, your name, the time of “simple” definitions for people is over, WHICH, by the way, they still, by the way, yet, alas, DO NOT REALIZE, because the cap. TO THIS mode of production, but which is already a historical ANACHRONISM!!!

digiandr 27.12.2016 19:10

know and understand the same thing.

banner_ 27.12.2016 22:00

If freedom is a recognized necessity, then permissiveness is a trampled necessity

Vasily Vasiliev 28.12.2016 07:54

The Marxist interpretation of freedom is pure verbiage and substitution of concepts. The concept of freedom means liberation from something. Freedom - from rights, from duties, from slavish dependence, from fetters, from moral principles. At the same time, phrases like: freedom of speech, or freedom of choice, are not true in principle. How can one be free from the word? From this promise it is possible, but from the word how? Or how can one have free choice? Free from what exactly? From restrictions, or from what? And the thing is that the word freedom has replaced the concept of WILL. Your will to choose, your will to express your words and desires. THE MOST FREE PERSON is a SLAVE, because HE IS FREED FROM ALL RIGHTS, including the main human right, FROM THE RIGHT TO MANAGE HIS LIFE HIMSELF. Since the arrangement and living conditions of a slave are dealt with by his master, the lord. But on the other hand, a FREE MAN cannot be a slave by definition, since HIS ALL LIFE COMPLETELY DEPENDS ON HIS WILL. The substitution of the concepts of FREEDOM and WILL is beneficial for slave owners, so that the slaves live IN THE WORLD FREE OF RIGHTS and DO NOT STRIVE FOR WILL. Marx wrote about a communist society, where the fate of the common people is to be a slave to the ruling elite. It was precisely such a slave-owning society that was built by Lenin. All the people of the USSR were a slave of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the emperor (Secretary General of the Central Committee). The fact that the name of the central authority does not sound like a boyar Duma, or a monarch, an emperor, does not change the essence of the situation. Ordinary people were slaves, since their lives completely depended on the will of the lords. The only plus of the slave-owning society built by Lenin is its economic model.

Alexander, Asha, Chelyab.reg. 28.12.2016 10:53

The concepts and categories of philosophy are larger in scope than the legal instruments of rights and obligations. This is the same as making cars out of meatballs and trying to drive them. Shouted. Vasily Vasilyev about his own mental abilities. Directly according to Peter I: “I order the boyars in the Duma to speak according to the unwritten, so that everyone’s nonsense is visible.”

your name 28.12.2016 11:32

First, one must recognize the need for freedom. Many do not need freedom, because it implies responsibility to oneself. This responsibility is easier to shift to the owner. That is why we see so many serfs describing the delights of serf service.

Rovshan 09.01.2017 16:20

And what about freedom as a conscious accident ..?

teacher 01.04.2017 16:12

Tatyana Vasilyeva - 5+.

Hosting 14.09.2017 04:04

To legitimize such limited freedom, this formula “freedom as a conscious necessity” was invented. This is human freedom - to proudly proclaim freedom only because you understand your desire, but completely ignore the reasons for this desire.