Russian-Iranian wars. Iran and European countries in the XVIII Russian-Persian war of 1804 1813 main events

Russian - Persian war of 1804-1813

The activity of Russia's policy in the Transcaucasus was connected mainly with Georgia's persistent requests for protection from the Turkish-Iranian onslaught. During the reign of Catherine II, the Georgievsky Treaty (1783) was concluded between Russia and Georgia, according to which Russia was obliged to defend Georgia. This led to a clash, first with Turkey, and then with Persia (until 1935, the official name of Iran), for which Transcaucasia has long been a sphere of influence. The first clash between Russia and Persia over Georgia took place in 1796, when Russian troops repulsed the invasion of Iranian troops into Georgian lands. In 1801, Georgia, by the will of its king George XII, joined Russia.

GeorgeXII

This forced St. Petersburg to get involved in the complex affairs of the troubled Transcaucasian region. In 1803, Mingrelia joined Russia, and in 1804, Imeretia and Guria. This caused dissatisfaction with Iran, and when in 1804 Russian troops occupied the Ganja Khanate (for the raids of Ganja detachments on Georgia),

After the annexation of Georgia to Russia and the granting to it of the administration that existed in other regions of the Empire, the pacification of the Caucasus became a necessary, albeit extremely difficult, task for Russia, with the main attention being paid to the establishment in Transcaucasia. By annexing Georgia, Russia became openly hostile towards Turkey, Persia and the mountain peoples. The petty sovereign Transcaucasian princes, who managed to become independent, taking advantage of the weakness of the Georgian kingdom, under whose protectorate they were, looked extremely hostilely at the strengthening of Russian influence in the Caucasus and entered into secret and open relations with the enemies of Russia. In such a difficult situation, the choice of Alexander I settled on the book. Tsitsianov.

Pavel Dmitrievich Tsitsianov

Realizing that successful operations in Georgia and the Transcaucasus required not only a smart and courageous person, but also someone familiar with the area, with the customs and habits of the highlanders, the Emperor recalled the commander-in-chief Knorring appointed by Paul I and, on September 9, 1802, appointed Astrakhan military governor and chief commander in Georgia, Prince. Tsitsianova. Entrusting him with this responsible post and informing him of the plan of Count Zubov, which consisted in the occupation of lands from the Rion River to the Kura and Araks, to the Caspian Sea and beyond, Alexander I ordered: by firm behavior try to acquire a power of attorney to the government not only of Georgia, but also of various neighboring possessions. “I am sure,” the Emperor wrote to Tsitsianov, “that convinced by the importance of the service entrusted to you, and guided both by the knowledge of my rules for this land and by your own prudence, you will fulfill your duty with the impartiality and rightness that I have in you always guessed and found."

Realizing the seriousness of the danger posed by Persia and Turkey, Tsitsianov decided to secure our borders from the east and south and began with the Khanate of Ganzhinsky, the closest to Georgia, which had already been conquered by c. Zubov, but, upon the removal of our troops, again recognized the power of Persia. Convinced of the impregnability of Ganja and hoping for the help of the Persians, its ruler, Javat Khan, considered himself safe, especially since the Dzhars and Elisuans, convinced by the Dagestan princes, had fallen out of obedience, despite the convictions of Tsitsianov. Javat Khan, in response to a letter from Tsitsianov inviting him to submit, declared that he would fight the Russians until he won. Then Tsitsianov decided to act energetically. Reinforcing the detachment of Gulyakov, who had a permanent post on the river. Alazani, near Aleksandrovsk, Tsitsianov with 4 infantry battalions, part of the Narva Dragoon Regiment, several hundred Cossacks, a detachment of the Tatar cavalry, with 12 guns, moved to Ganzha. Tsitsianov did not have a plan of the fortress and a map of its environs. I had to do reconnaissance on the spot. On December 2, for the first time, Russian troops clashed with the troops of Javat Khan, and on December 3, Ganzha was besieged and bombardment began, since Javat Khan refused to surrender the fortress voluntarily. Tsitsianov did not dare to storm Ganzha for a long time, fearing to suffer heavy losses. The siege lasted for four weeks, and only on January 4, 1804, the main mosque of Ganzhi was already "turned into a temple to the true God," as Tsitsianov put it in his letter to General Vyazmitinov. The assault on Ganja cost 38 men killed and 142 wounded. Javat Khan was among those killed by the enemy.

Javat Khan

The Russians got into booty: 9 copper guns, 3 cast iron, 6 falconets and 8 banners with inscriptions, 55 pounds of gunpowder and a large grain supply.

Persia declared war on Russia. In this conflict, the number of Persian troops many times exceeded the Russian ones. The total number of Russian soldiers in Transcaucasia did not exceed 8 thousand people. They had to operate on a large territory: from Armenia to the shores of the Caspian Sea. In terms of armament, the Iranian army, equipped with British weapons, was not inferior to the Russian one. Therefore, the final success of the Russians in this war was associated primarily with a higher degree of military organization, combat training and courage of the troops, as well as with the military leadership talents of military leaders. The Russian-Persian conflict marked the beginning of the hardest military decade in the history of the country (1804-1814), when the Russian Empire had to fight almost along the entire perimeter of its European borders from the Baltic to the Caspian Sea. This demanded from the country an unprecedented tension since the Northern War.

Campaign of 1804 .

The main hostilities of the first year of the war unfolded in the area of Erivan (Yerevan). The commander of the Russian troops in Transcaucasia, General Pyotr Tsitsianov, began the campaign with offensive actions.

The main forces of the Persians, under the command of Abbas Mirza himself, had already crossed the Araks and entered the Erivan Khanate.

Abbas Mirza

On June 19, Tsitsianov approached Etchmiadzin, and on the 21st, the eighteen thousandth Persian corps surrounded Tsitsianov, but was driven back with heavy losses. On the 25th of June the attack resumed and again the Persians were defeated; Abbas Mirza retreated behind the Araks. Notifying the Erivan Khan about this, Tsitsianov demanded that he surrender the fortress and take an oath of allegiance. The treacherous khan, wanting to get rid of the Russians and ingratiate himself with the Shah of Persia, sent to ask him to come back. The result of this was the return of the 27,000th Persian army, encamped at the village of Kalagiri.

Abbas Mirza was making preparations for decisive action here, but Tsitsianov warned him. On June 30, a three thousandth detachment of Russian troops crossed the river. Zangu and, repulsing the sortie made from the Erivan fortress, attacked the enemy, who occupied a strong position on the heights. At first, the Persians stubbornly defended themselves, but in the end they were forced to retreat to their camp, located three miles from the battlefield. The small number of cavalry did not allow Tsitsianov to pursue the enemy, who left his camp and fled through Erivan. On this day, the Persians lost up to 7,000 killed and wounded, the entire convoy, four banners, seven falconets, and all the treasures looted along the way. Tsitsianov's award for the victory was (July 22, 1804) the Order of St. Vladimir 1st class. Having won a victory over the Persians, Tsitsianov directed his forces against the Erivan Khan and on July 2 besieged Erivan. At first, the khan resorted to negotiations, but since Tsitsianov demanded unconditional surrender, on July 15, part of the garrison and several thousand Persians attacked the Russian detachment. After a ten-hour battle, the attackers were repelled, losing two banners and two cannons. On the night of July 25, Tsitsianov sent Major General Portnyagin with part of his troops to attack Abbas Mirza, whose camp was located in a new place, not far from Erivan. This time the victory was on the side of the Persians and Portnyagin was forced to retreat. Tsitsianov's position became more and more difficult. Intense heat exhausted the army; convoys with provisions came with a significant delay or did not come at all; the Georgian cavalry, sent by him back to Tiflis, was captured by the enemy on the road and taken to Tehran; Major Montresor, who held a post at the village of Bombaki, was killed by the Persians, and his detachment was exterminated; Lezgins made raids; the Karabakh people invaded the Yelisavetpol region; the Ossetians also began to worry; the detachment's relations with Georgia were interrupted. In a word, Tsitsianov's position was critical; Petersburg and Tiflis were waiting for news of the death of the detachment and Tiflis was preparing for defense. Only Tsitsianov did not lose heart. Unbending will, faith in himself and in his army gave him the strength to continue the siege of Erivan as persistently as before. He hoped that with the onset of autumn the Persian troops would withdraw and the fortress, without their support, would be forced to surrender; but when the enemy burned all the grain in the vicinity of Etchmiadzin and Erivan, and the detachment began to face inevitable hunger, Tsitsianov faced a dilemma: lift the siege or take the fortress by storm. Tsitsianov, true to himself, chose the latter. Of all the officers he invited to the military council, only Portnyagin joined his opinion; everyone else was against the assault; yielding to the majority of votes, Tsitsianov gave the order to retreat. On September 4, Russian troops set out on a return campaign. During the ten-day retreat, up to 430 people fell ill and about 150 died.

Having refused to take Erivan, Tsitsianov hoped that through peaceful negotiations he would be able to expand the borders of Russia, and his attitude towards the mountain khans and rulers was the opposite of that followed by the Russian government before Tsitsianov. “I dared,” he wrote to the chancellor, “to adopt a rule contrary to the system that used to be here and instead of paying a certain kind of tribute for their imaginary allegiance with salaries and gifts determined to soften the mountain peoples, I myself demand tribute.” In February 1805, Prince. Tsitsianov accepted an oath of allegiance to the Russian Tsar from Ibraim Khan of Shushinsky and Karabakh; in May, Selim Khan of Sheki took the oath; in addition, Dzhangir Khan of Shagakh and Budakh Sultan of Shuragel expressed their obedience; having received a report on these accessions, Alexander I awarded Tsitsianov with a cash lease in the amount of 8,000 rubles. in year.

But although the troops of Tsitsianov in the battle of Kanagir (near Erivan) defeated the Iranian army under the command of Crown Prince Abass-Mirza, the Russian forces were not enough to take this stronghold. In November, a new army under the command of Shah Feth-Ali approached the Persian troops.

Shah Feth-Ali

The Tsitsianov detachment, which had already suffered significant losses by that time, was forced to lift the siege and retreat to Georgia.

Campaign of 1805 .

The failure of the Russians under the walls of Erivan strengthened the confidence of the Persian leadership. In June, a 40,000-strong Persian army under the command of Prince Abbas Mirza moved through the Ganja Khanate to Georgia. On the Askeran river (the region of the Karabakh ridge), the vanguard of the Persian troops (20 thousand people) met stubborn resistance from the Russian detachment under the command of Colonel Karyagin (500 people), which had only 2 guns. From June 24 to July 7, the rangers of Karyagin, skillfully using the terrain and changing positions, heroically repelled the onslaught of a huge Persian army. After a four-day defense in the Karagach tract, on the night of June 28, the detachment fought its way into the Shah-Bulakh castle, where it was able to hold out until the night of July 8, and then secretly left its fortifications.

Shah Bulakh Castle

The selfless resistance of Karyagin's warriors actually saved Georgia. The delay in the advance of the Persian troops allowed Tsitsianov to gather forces to repel the unexpected invasion. On July 28, in the battle of Zagama, the Russians defeated the troops of Abbas Mirza. His campaign against Georgia was stopped and the Persian army retreated. After that, Tsitsianov transferred the main hostilities to the Caspian coast. But his attempts to carry out a naval operation with the aim of capturing Baku and Rasht ended in vain.

Campaign of 1806 .

P.D. Tsitsianov set off on a campaign against Baku.

The Russians were moving through the Shirvan Khanate and, on this occasion, Tsitsianov managed to persuade the Shirvan Khan to join Russia. Khan took the oath of citizenship on December 25, 1805. From Shirvan, the prince informed the Khan of Baku about his approach, demanding the surrender of the fortress. After a very difficult transition through the Shemakha mountains, Tsitsianov with his detachment approached Baku on January 30, 1806.

Sparing the people and wanting to avoid bloodshed, Tsitsianov once again sent the khan an offer to submit, and he set four conditions: a Russian garrison would be stationed in Baku; Russians will manage the income; the merchant class will be guaranteed against harassment; the eldest son of the khan will be delivered to Tsitsianov as an amanat. After rather long negotiations, the khan declared that he was ready to submit to the Russian commander in chief and betray himself into eternal allegiance to the Russian Emperor. In view of this, Tsitsianov promised to leave him the owner of the Baku Khanate. Khan agreed to all the conditions set by the prince, and asked Tsitsianov to set a date for accepting the keys. The prince appointed February 8. Early in the morning he went to the fortress, having with him 200 people who were supposed to stay in Baku as a garrison. Half a verst before the city gates, Baku foremen were waiting for the prince with keys, bread and salt, and, bringing them to Tsitsianov, announced that the khan did not believe in his complete forgiveness and asked the prince for a personal meeting. Tsitsianov agreed, gave back the keys, wishing to receive them from the hands of the Khan himself, and rode forward, ordering Lieutenant Colonel Prince Eristov and one Cossack to follow him. About a hundred steps from the fortress, Hussein-Kuli-khan came out to meet Tsitsianov, accompanied by four Bakuvians, and while the khan, bowing, brought the keys, the Bakuvians fired; Tsitsianov and Prince. Eristov fell; the khan's retinue rushed to them and began to cut their bodies; at the same time, artillery fire on our detachment opened from the city walls.

The body of the book Tsitsianov was first buried in a hole, at the very gate where he was killed. General Bulgakov, who took Baku in the same 1806, gave his ashes to be buried in the Baku Armenian Church, and who ruled in 1811-1812. Georgia Marquis Paulucci moved him to Tiflis and buried him in the Sioni Cathedral. A monument with an inscription in Russian and Georgian was erected over the grave of Tsitsianov.

I.V. Gudovich

General Ivan Gudovich was appointed commander-in-chief, who continued the offensive in Azerbaijan. In 1806, the Russians occupied the Caspian territories of Dagestan and Azerbaijan (including Baku, Derbent, and Cuba). In the summer of 1806, the troops of Abbas-Mirza, who were trying to go on the offensive, were defeated in Karabakh. However, the situation soon became more complicated. In December 1806, the Russian-Turkish war began. In order not to fight on two fronts with his extremely limited forces, Gudovich, taking advantage of the hostile relations between Turkey and Iran, immediately concluded a truce with the Iranians and began military operations against the Turks. The year 1807 passed in peace negotiations with Iran, but they did not lead to anything. In 1808 hostilities resumed.

Campaign of 1808-1809 .

In 1808 Gudovich transferred the main military actions to Armenia. His troops occupied Etchmiadzin (a city west of Yerevan) and then laid siege to Erivan. In October, the Russians defeated the troops of Abbas-Mirza at Karababa and occupied Nakhichevan. However, the assault on Erivan ended in failure, and the Russians were forced to retreat from the walls of this fortress a second time. After that, Gudovich was replaced by General Alexander Tormasov, who resumed peace negotiations. During the negotiations, troops under the command of the Iranian Shah Feth-Ali unexpectedly invaded northern Armenia (the Artik region), but were repelled. The attempt of Abbas-Mirza's army to attack Russian positions in the Ganja region also ended in failure.

A.P. Tormasov in the army

Campaign of 1810-1811 .

In the summer of 1810, the Iranian command planned to launch an offensive against Karabakh from its Meghri stronghold (a mountainous Armenian village located on the left bank of the Arak River). To prevent offensive actions of the Iranians, a detachment of rangers under the command of Colonel Kotlyarevsky (about 500 people) went to Meghri, who on June 17 managed to seize this stronghold with a surprise attack, where there was a garrison of 1.5 thousand with 7 batteries. Russian losses amounted to 35 people. Iranians lost more than 300 people. After the fall of Meghri, the southern regions of Armenia received reliable protection from Iranian invasions. In July, Kotlyarevsky defeated the Iranian army on the Arak River. In September, Iranian troops attempted to launch a western offensive on Akhalkalaki (southwestern Georgia) to link up with Turkish troops there. However, the Iranian offensive in the area was repulsed. In 1811 Tormasov was replaced by General Paulucci. However, the Russian troops did not take active actions during this period due to the limited number and the need to wage a war on two fronts (against Turkey and Iran). In February 1812 Paulucci was replaced by General Rtishchev, who resumed peace negotiations.

Campaign of 1812-1813 .

P.S. Kotlyarevsky

At this time, the fate of the war was actually decided. A sharp turn is connected with the name of General Pyotr Stepanovich Kotlyareveky, whose bright talent as a commander helped Russia to end victoriously a protracted confrontation.

Battle of Aslanduz (1812) .

After Tehran received news of the occupation of Moscow by Napoleon, the negotiations were interrupted. Despite the critical situation and the obvious lack of forces, General Kotlyarevsky, who was given freedom of action by Rtishchev, decided to seize the initiative and stop the new offensive of the Iranian troops. He himself moved with a 2,000-strong detachment towards the 30,000-strong army of Abbas Mirza. Using the surprise factor, Kotlyarevsky's detachment crossed the Arak in the Aslanduz region and on October 19 attacked the Iranians on the move. They did not expect such a quick attack and retreated in confusion to their camp. In the meantime, night fell, hiding the real number of Russians. Having instilled in his soldiers an unshakable faith in victory, the fearless general led them to attack against the entire Iranian army. Courage trumped strength. Breaking into the Iranian camp, a handful of heroes with a bayonet charge caused an indescribable panic in the camp of Abbas Mirza, who did not expect a night attack, and put the whole army to flight. The damage to the Iranians amounted to 1,200 people killed and 537 captured. The Russians lost 127 people.

Battle of Aslandz

This victory of Kotlyarevsky did not allow Iran to seize the strategic initiative. Having crushed the Iranian army near Aslanduz, Kotlyarevsky moved to the Lankaran fortress, which covered the way to the northern regions of Persia.

Capture of Lankaran (1813) .

After the defeat near Aslanduz, the Iranians pinned their last hopes on Lankaran. This strong fortress was defended by a 4,000-strong garrison under the command of Sadyk Khan. Sadyk Khan answered the offer to surrender with a proud refusal. Then Kotlyarevsky ordered his soldiers to take the fortress by storm, declaring that there would be no retreat. Here are the words from his order, read out to the soldiers before the battle: “Having exhausted all means to force the enemy to surrender the fortress, finding him adamant to that, there is no longer any way left to conquer the fortress with this Russian weapon, as soon as by the force of the assault ... We must take the fortress or everyone to die, why are we sent here ... so we will prove, brave soldiers, that nothing can resist the power of the Russian bayonet ... " On January 1, 1813, an attack followed. Already at the beginning of the attack, all the officers were knocked out in the forefront of the attackers. In this critical situation, Kotlyarevsky himself led the attack. After a cruel and ruthless assault, Lankaran fell. Less than 10% of its defenders survived. Russian losses were also great - about 1 thousand people. (50% composition). During the attack, the fearless Kotlyarevsky also received severe injuries (he became disabled and left the armed forces forever). Russia has lost a bright successor of the Rumyantsev-Suvorov military tradition, whose talent was only just beginning to work "Suvorov's miracles."

assault on Lankaran

Peace of Gulistan (1813) .

The fall of Lankaran decided the outcome of the Russian-Iranian war (1804-1813). It forced the Iranian leadership to stop hostilities and agree to the signing of the Gulistan peace [concluded 12(24). October 1813 in the village of Gulistan (now the village of Gulustan in the Goranboy region of Azerbaijan)]. A number of Transcaucasian provinces and khanates (Derbent Khanate) went to Russia, which received the exclusive right to maintain a navy in the Caspian Sea. Russian and Iranian merchants were allowed to trade freely on the territory of both states.

Throughout its history, Russia has always stood apart. Constantly changing shape as its rulers annexed neighboring territories, Russia was an empire incomparable in scale with any of the European countries. Torn between the obsession of insecurity and missionary zeal, between the demands of Europe and the temptations of Asia, the Russian Empire has always played a part in the European balance, but spiritually it has never been a part of it. Analysts often explain Russian expansionism as a product of a sense of insecurity. However, Russian writers much more often justified Russia's desire to expand its borders with its messianic vocation.

Since ancient times, the Caucasus has been an important strategic and economic region for the countries bordering on it. The most important trade routes from Europe to Asia from the Middle East to the Middle East passed through it. Transcaucasia is located between the Black and Caspian Seas, which also increased its importance as an area convenient for transit trade. In strategic terms, the possession of the territory of the Caucasus made it possible not only to control transit trade, but also to firmly establish itself in the Black and Caspian Seas. For many centuries, the territory of Transcaucasia remained the scene of devastating wars, passing from hand to hand. It was divided into many small estates with great ethnic and socio-economic diversity.

The economic and political factors that prompted tsarism to establish its dominion over the South Caucasus were most thoroughly and clearly developed by the Deputy Minister of Finance, Count D. A. Guryev, in 1810, who took the post of minister. In his note, he pointed out that the main reason for the stagnation of the Caspian trade "are the whirlpools in Persia." It seemed to him that Russia had no other means to correct the situation "... how to occupy the entire eastern coast of the Caspian Sea." In principle, he advocated the transfer of the state borders of the Russian Empire to the southern "natural limits of the Caucasus".

Even as a result of the Persian campaign of 1722-23, Russia annexed part of Dagestan and Azerbaijan, however, due to the aggravation of relations between Russia and Turkey, the Russian government, trying to get the support of Iran, and also due to a lack of forces in 1732-35, abandoned the occupied territories in Dagestan and Azerbaijan.

In the second half of the 18th century, the activity of Russia's policy in the Transcaucasus was mainly associated with Georgia's persistent requests for protection from the Turkish-Iranian onslaught.

In 1783, Russia and the Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti (Eastern Georgia) signed an agreement. This treaty, called the Treaty of Georgievsk, was signed on July 24 (August 4). The Georgian king Heraclius II recognized the protectorate of Russia, and Empress Catherine II vouched for the preservation of the integrity of the possessions of Heraclius. According to the treaty, Russia was obliged to provide military assistance to Georgia. This help was needed in 1795, when Iranian troops under the command of Agha Mohammed Khan invaded Transcaucasia.

Agha Mohammed Khan, a terrible historical figure, "famous" for his extraordinary cruelty and, according to his contemporaries, possessing the basest human vices, set about conquering Transcaucasia. On the eve of the campaign, he demanded obedience from Ganja and Erivan, as well as their participation in the expedition against Georgia. These regions submitted to him without resistance. The Derbent Khan also went over to his side. At the beginning of September 1795, Agha Mohammed Khan approached Tiflis and captured it. For several days, vandalism reigned in the city. Tiflis was destroyed to such an extent that after the departure of the Persians, King Erekle II had an idea to move the capital to another place.

In the spring of 1796 Russia reacted. In April, the Caspian Corps, numbering 13 thousand people, set out from Kizlyar. Russian troops moved into the Azerbaijani provinces of Iran, on May 10 (21) they stormed Derbent, and on May 15 (26) occupied Baku and Cuba without a fight. In November, they reached the confluence of the Kura and Araks. However, after the death of Catherine II and the accession to the throne of Paul I, Russia's foreign policy changed, and the troops from Transcaucasia were withdrawn.

The Persian threat strengthened the pro-Russian orientation of many peoples of the Caucasus. They were forced to strive for voluntary entry into the Russian Empire, which would save them from the prospect of being subjugated by Iranian shahs and Turkish sultans.

In Soviet historiography (including Transcaucasian historians), the orientation of the Caucasian peoples towards Russia, which supposedly arose almost from the 15th-16th centuries, was somewhat exaggerated. At the same time, differences in the religious and socio-political situation of the peoples of the Caucasus were poorly taken into account. As for the Georgian and Armenian population, their pro-Russian orientation was indeed historically inevitable. The position of the Turkic-Muslim population and many local rulers was different. To retain power, because of the internal political struggle and intrigue, they subordinated their actions to selfish goals that go against national interests. But also in Georgia, various groups tried to use the contradictions between Russia and Persia and Turkey, flirting with the latter. In some regions of the Caucasus, pockets of resistance to the assertion of Russian domination arose. They were led by large feudal lords and Muslim clergy who gravitated towards Persia and Turkey.

Russia's advance into the Caucasus was dictated by economic, geopolitical and strategic reasons. The inclusion of the Caucasus into Russia opened up broad prospects for the development of trade through the Black Sea ports, as well as through Astrakhan, Derbent and Kizlyar in the Caspian. In the future, the Caucasus could become a source of raw materials for the developing Russian industry and a market for its goods. The expansion of the territory of the Russian Empire in the Caucasus in geopolitical terms contributed to the strengthening of the southern borders along natural (mountain) barriers, made it possible for political and military pressure on Turkey and Persia. From the point of view of Russia's strategic interests, British interference in the affairs of the Transcaucasus caused concern. Back in the middle of the 18th century, Great Britain used its influence in Persia to penetrate the Transcaucasus and secure access to the Caspian Sea. She considered this region, on the one hand, as a means of political pressure on Russia, on the other hand, as a factor in protecting her interests in the Middle and Near East, the security of possessions in India.

In 1801, Georgia, by the will of its king George XII, joined Russia. This forced St. Petersburg to get involved in the complex affairs of the troubled Transcaucasian region. In 1803, Mingrelia joined Russia, and in 1804, Imeretia and Guria. When in 1804 Russian troops occupied the Ganja Khanate (for the raids of Ganja detachments on Georgia), this caused dissatisfaction in Iran.

Iran at that time entered into an alliance with Great Britain, Shah Feth-Ali on May 23 (June 1), 1804 presented an ultimatum to Russia demanding the return of Ganja, as well as the withdrawal of Russian troops from Transcaucasia, and was refused. On June 10 (22), diplomatic relations broke off, and then hostilities began.

Rejecting the Shah's ultimatum, Russia was forced to go to war with Iran. So St. Petersburg, nurturing the idea of saving the same faith in Georgia, but at the same time keeping in mind its own military-strategic goals in the Transcaucasus, was involved thanks to the Georgian tavads and General Tsitsianov in one of the hard and long wars. It is worth emphasizing that in the war that began between Russia and Iran, more than Petersburg and Tehran, the Georgian nobility was interested - both of its parties - pro-Russian and anti-Russian, as well as Tsitsianov, who hatched plans for the return of the Empire to its "ancient borders". As noted, the problem of "ancient borders", essentially unjustified and reflecting only a special degree of aggressiveness of the Georgian nobility, arose in Russian-Georgian relations before. But earlier no one dared to specifically formulate the "limits" of these borders, which were claimed by the tawadas. Under the influence of the latter, they were first identified by Prince Tsitsianov. At the beginning of 1805, he declared that “Gurzhistan Welshism,” as it was customary to call the future Georgia, “stretched from Derbent, on the Caspian Sea, to Abkhazetia, on the Black Sea, and across from the Caucasus Mountains to the Kura and Arak rivers.” The Georgian tavads were the only ones who, in their relations with Russia, raised the issue of a territorial retrospective in the Caucasus. Another thing that attracted attention was the territorial claims of the Georgian nobility, which were announced by Prince Tsitsianov; Georgian territories never reached Derbent and did not extend "from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea." There was no moment in history when Georgia from the Alazani Valley entered the Djaro-Belokan Upland and in some way - military, political or otherwise came into contact with Dagestan Derbent. In the 17th and 18th centuries something else was observed - the displacement of the Georgian population from Kakheti by large detachments of the mountaineers of Dagestan, the devastation of the Alazani valley and the compact settlement of the mountaineers in this valley. The result of this was the loss of Telavi, his capital, by Heraclius II, and the relocation of the royal family to Tiflis.

In the conflict of 1804-1813. the number of Persian troops many times exceeded the Russian. The total number of Russian soldiers in Transcaucasia did not exceed 8 thousand people. They had to operate on a large territory: from Armenia to the shores of the Caspian Sea. In terms of armament, the Iranian army, equipped with British weapons, was not inferior to the Russian one. Therefore, the final success of the Russians in this war was associated primarily with a higher degree of military organization, combat training and courage of the troops, as well as with the military leadership talents of military leaders.

The main hostilities of the first year of the war unfolded in the area of Erivan (Yerevan). The commander of the Russian troops in Transcaucasia, General Pyotr Tsitsianov, moved into the Erivan Khanate (the territory of present-day Armenia) dependent on Iran and laid siege to its capital Erivan (Fig. 2), but the Russian forces were not enough. In November, a new army under the command of Shah Feth-Ali approached the Persian troops. The Tsitsianov detachment, which had already suffered significant losses by that time, was forced to lift the siege and retreat to Georgia.

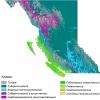

Rice. 2

Armenian militias and Georgian cavalry took the side of the Russians. However, in Kabarda, Dagestan, and partly in Ossetia, anti-Russian sentiments were strong, which hampered the actions of the Russian army. A dangerous situation also developed in the area of the Georgian Military Highway, which prevented the supply of Russian troops.

At the most difficult moment of the beginning of the Russian-Iranian war, Ossetian rebels numbering 3,000 people, led by Akhmet Dudarov, closed the Georgian Military Highway and led a long siege of Stepan-Tsminda, where the Russian team was located. The Russian command, cut off by the rebels from the mother country, was forced to withdraw troops from the Iranian front and wage fierce battles with the Ossetian and Georgian peasantry. The military actions of the Russian troops in the South Ossetian direction were led by General Tsitsianov himself in order to free the Georgian Military Highway from the rebels and resume the movement of military transports along it, heading to the Russian-Iranian front. After the punitive measures of the commander, many settlements on the small map of Ossetia disappeared: they were either destroyed or burned.

In 1805, Abbas Mirza and Baba Khan moved to Tiflis, but Russian detachments blocked their path. On July 9, near the Zagama River, Abbas-Mirza suffered a serious setback in a battle with a detachment of Colonel Karyagin and refused to go to Georgia. At the end of the year, Tsitsianov achieved the annexation of the Shirvan Khanate to Russia and moved to Baku. However, on February 20, 1806, Baku Khan Hussein Quli Khan treacherously killed the general during negotiations. Russian troops tried to take Baku by storm, but were repelled.

After the assassination of Tsitsianov, an anti-Russian uprising began in Shirvan, Shusha and Nukha. The 20,000-strong army of Abbas-Mirza was sent to help the rebels, but it was defeated in the Khanaship Gorge by General Nebolsin. By the beginning of November, the uprising was crushed by the troops of Count Gudovich, who replaced Tsitsianov, and Derbent and Nukha were again in the hands of the Russians.

In 1806, the Russians occupied the Caspian territories of Dagestan and Azerbaijan (including Baku, Derbent, and Cuba). In the summer of 1806, the troops of Abbas-Mirza, who were trying to go on the offensive, were defeated in Karabakh. However, the situation soon became more complicated.

In December 1806, the Russian-Turkish war began. In order not to fight on two fronts with his extremely limited forces, Gudovich, taking advantage of the hostile relations between Turkey and Iran, immediately concluded the Uzun-Kilis truce with the Iranians and began military operations against the Turks. But in May 1807, Feth-Ali entered into an anti-Russian alliance with Napoleonic France, and in 1808 hostilities resumed.

In 1808 Gudovich transferred the main military actions to Armenia. His troops occupied Etchmiadzin (a city west of Yerevan) and then laid siege to Erivan. In October, the Russians defeated the troops of Abbas-Mirza at Karababa and occupied Nakhichevan. However, the assault on Erivan ended in failure, and the Russians were forced to retreat from the walls of this fortress a second time. After that, Gudovich was replaced by General Alexander Tormasov, who resumed peace negotiations. During the negotiations, the troops of the Iranian Shah Feth-Ali unexpectedly invaded northern Armenia (the Artik region), but were repelled. The attempt of Abbas-Mirza's army to attack Russian positions in the Ganja region also ended in failure.

The turning point came in the summer of 1810. On June 29, the detachment of Colonel P.S. Kotlyarevsky captured the fortress of Migri and, coming to the banks of the Araks, defeated the vanguard of the army of Abbas Mirza. Iranian troops tried to invade Georgia, but on September 18, the army of Ismail Khan was defeated at the fortress of Akhalkalaki by a detachment of Marquis F.O. Paulucci. More than a thousand Iranians, led by the commander, were captured.

On September 26, Abbas-Mirza's cavalry was defeated by Kotlyarevsky's detachment. The same detachment captured Akhalkalaki with a sudden blow, capturing the Turkish garrison of the fortress.

In 1811, there was a lull in the fighting again. In 1812, taking advantage of the diversion of Russian forces to fight against Napoleon, Abbas-Mirza captured Lankaran. However, in late October - early November, he suffered two defeats from Kotlyarevsky's troops. In January 1813, Kotlyarevsky took Lankaran by storm. During the attack, the general was seriously wounded and was forced to leave the service.

The rulers of Persia, frightened by the defeat of Napoleon and the defeat near Aslanduz, hastily entered into peace negotiations with Russia. On October 12 (24), 1813, the Gulistan peace treaty was signed in the Gulistan tract in Karabakh.

According to the text of the agreement, Lieutenant General N.F. Rtishchev from the Russian Empire and Mirza Abul Hassan Khan - from the Persian side proclaimed the cessation of all hostilities between the parties and the establishment of eternal peace and friendship on the basis of status quo ad presentem, that is, each side remained in possession of those territories that at that time were in her power. This meant the recognition by Iran of the territorial conquests of the Russian Empire, which were secured by Art. 3 of the Gulistan Treaty as follows. Iran renounced claims to the Karabakh and Ganzhin (after conquering the Elisavetpol province) khanates, as well as the khanates: Sheki Shirvan, Derbent, Cuban, Baku and Talysh. Also, all of Dagestan, Georgia with the Shuragel province, Imeretia, Guria, Mingrelia and Abkhazia departed to Russia (see Appendix 1).

The accession of a significant part of the Transcaucasus to Russia saved the peoples of Transcaucasia from the destructive invasions of the Persian and Turkish invaders, involved the region in the general course of the economic, cultural, socio-political life of Russia.

According to Art. 5 Russia received the exclusive right to keep warships on the Caspian Sea. Both Russian and Persian merchant ships had the right to move freely and moor on its shores.

All prisoners of both sides returned for a period of three months with the supply of food and travel expenses for each side. Those who fled were willfully granted freedom of choice and amnesty.

The Russian Empire undertook to recognize the heir appointed by the shah and to support him in the event of a third party interfering in the affairs of Persia and not to enter into disputes between the shah's sons until such time as the then ruling shah asks for her.

Art. 8-10 agreements regulated bilateral trade and economic relations. Citizens of both sides received the right to trade in the territory of another country. Duties on goods brought by Russian merchants to Persian cities or ports were set at five percent. In the event of the death of Russian citizens in Iran, the property was transferred to relatives.

Ministers or envoys were to be received according to their rank and the importance of the affairs entrusted (v. 7), which meant the restoration of diplomatic relations.

The peace of Gulistan was not published immediately after the conclusion, for 4 years there was a struggle to revise its articles. Persia, with the support of Great Britain, insisted on returning to the borders of 1801, i.e. return under the rule of the Shah of the entire Eastern Caucasus. Russia sought to weaken English influence in Persia and strengthen its economic positions. In 1818, as a result of the mission of A.P. Yermolov in Persia, the Gulistan peace was fully recognized by Persia and entered into force.

Thus, the first Russian-Iranian war was due to the desire of both states to establish their influence over an important strategic region, and as a result of the defeat of Iran during the hostilities, the Russian Empire established its dominance in a large territory of the Caucasus, as well as trade duties enslaving in relation to Persia.

Expansion of European powers in Iran. Accession of Transcaucasia to Russia.

From the end of the 18th - beginning of the 19th centuries. Iran is becoming important in connection with the struggle between England and France for dominance in Europe and the East. Considering the strategic position of Iran, they tried in every possible way to involve it in the struggle taking place between them. At the same time, both of these powers opposed Russia, which was trying to maintain dominance in Iran and Turkey over the peoples of Transcaucasia. The advance of Russia in the Transcaucasus, the annexation of Georgia in 1801 to Russia, its intervention in the defense of the Transcaucasian peoples caused two Russian-Iranian wars.

Back in 1800, an English mission was sent to Iran, headed by the captain of the troops of the East India Company, Malcolm. This mission was successful, since in 1801 an agreement was concluded with the Shah of Iran, according to which he undertook to send his troops to Afghanistan, to stop raids on the Indian possessions of England. Further, the Shah undertook to prevent the French from entering Iran and the coast of the Persian Gulf. England, for its part, was supposed to supply Iran with weapons in the event of a war between Iran and France and Afghanistan. At the same time, a trade agreement was signed with the Iranian government, confirming the privileges of the British, received earlier in 1763: the right to acquire and own land in Iran; the right to build trading posts on the coast of the Persian Gulf; the right to free trade throughout the country without paying import duties. This treaty marked the beginning of the transformation of Iran into a country dependent on England. In addition, the treaty of 1801 was directed against Russia.

During the reign of Napoleon, France twice tried to make its way to the East. Both attempts were unsuccessful. In Egypt, the French were defeated, and the joint Franco-Russian campaign against India never took place. However, French diplomats did not stop their activities in Iran. On the eve of the first Russian-Iranian war, the French government proposed to the Shah to conclude an alliance against Russia. Hoping for help from England, the Shah rejected the French offer.

First Russo-Iranian War

After the accession of Georgia to Russia, the tendencies of rapprochement with it intensified among the Azerbaijanis and Armenians. In 1802, an agreement was signed in Georgievsk on the transfer of a number of feudal lords of Dagestan and Azerbaijan to Russian citizenship and on a joint struggle against Iran. In 1804, Russian troops took Ganja and it was annexed to Russia. In the same year, the first Russian-Iranian war began. Encountering almost no resistance, the Russian troops advanced into the Yerevan Khanate. But this war dragged on due to the fact that in 1805 Russia joined the anti-Napoleonic coalition and its main forces were turned to fight France.

In the war with Russia, the Shah of Iran had high hopes for the help of England, but the latter, having become Russia's ally in the anti-Napoleonic coalition, was afraid to openly fulfill the terms of the 1801 treaty. This caused a deterioration in Anglo-Iranian relations. Taking advantage of this, Napoleon again offered his support to the Shah in the war against Russia. The defeats of the Iranians, the capture by Russia of Derbent, Baku and a number of other regions prompted the Shah to make an agreement with Napoleon.

In 1807, the Treaty of Finkenstein was signed between Iran and France. France guaranteed the inviolability of Iranian territory and pledged to make every effort to force Russia to evacuate troops from Georgia and other territories, as well as to provide the shah with weapons, equipment and military instructors.

The Iranian side, in turn, undertook to interrupt all political and commercial relations with England and declare war on her; to induce the Afghans to open the way for the French to India and to attach their military forces to the allied French army when it sets out to conquer India. However, the stay of French officers in Iran was short-lived. After the signing of the Treaty of Tilsit, the Treaty of Finkenstein lost all meaning for Napoleon.

The events in Tilsit also disturbed the British, who again resumed their negotiations with Iran and again offered him their help in the war with Russia. Pursuing its predatory goals and fearing the French plan to march on India, England develops an active diplomatic activity not only in Iran, but also in the north of India, in Afghanistan and Turkey. Having concluded a peace treaty with Turkey in 1809, British diplomats persuade her and Iran to agree among themselves on an alliance for a joint struggle against Russia. But neither the help of the British nor the alliance with the Turks saved the Iranian army from defeat.

In May 1812, the Russian-Turkish Treaty of Bucharest was concluded. Iran has lost its ally. In July of the same year, a treaty of alliance between England and Russia was signed in Orebro. The Iranian government has asked for peace. The negotiations ended with the signing of the Gulistan peace treaty in October 1813.

Under this agreement, the Iranian Shah recognized the Karabakh, Gandzha, Sheki, Shirvan, Derbent, Cuban, Baku and Talysh khanates, as well as Dagestan, Georgia, Imeretia, Guria, Mingrelia and Abkhazia, as belonging to the Russian Empire. Russia received the exclusive right to maintain a navy in the Caspian Sea; the right of free trade was granted to Russian merchants in Iran and Iranian merchants in Russia. The Treaty of Gulistan was a further step towards the establishment of a capitulation regime in Iran, which was initiated by the 1763 agreement with England and the Anglo-Iranian treaty of 1801.

Second Russo-Iranian War

The Iranian Shah and his entourage did not want to put up with the loss of the Azerbaijani khanates. Their revanchist ideas were inspired by English diplomacy. In November 1814, an agreement was signed between the Iranian government and England, directed against Russia and paving the way for new British conquests in the Middle East. Thus, the treaty provided for English "mediation" in determining the Russian-Iranian border; Iran was given a substantial annual subsidy in the event of a new war with any European power. Iran pledged to start a war with Afghanistan if the latter opens hostilities against British possessions in India. The conclusion of this treaty, firstly, made Iran politically dependent on England, and secondly, brought it into conflict with Russia.

British diplomacy in every possible way contributed to the Iranian-Turkish rapprochement, and then their military alliance against Russia. First, in order to persuade Russia to return the Azerbaijani khanates, an extraordinary ambassador was sent to St. Petersburg, whose diplomatic mission was not successful. British diplomacy played an important role in the disruption of Russian-Iranian negotiations. Having failed to achieve the desired through diplomatic means, in July 1826 Iran began military operations against Russia without declaring war. But the military victory again turned out to be on the side of the Russian troops and the Shah asked for peace. In February 1828, a Russian-Iranian peace treaty was signed in the town of Turkmanchay.

According to the Turkmanchay Treaty, Iran ceded to Russia the khanates of Yerevan and Nakhichevan; the shah renounced all claims to Transcaucasia; undertook to pay indemnity to Russia; the provision on the exclusive right of Russia to maintain a navy in the Caspian Sea was confirmed. A special act on trade between Russia and Iran was also signed here, according to which the procedure for resolving all contentious cases was determined; Russian subjects were given the right to rent and buy residential premises and warehouses; for Russian merchants, a number of privileges were established on the territory of Iran, which consolidated the unequal position of this country.

Huge funds spent on the war with Russia and on the payment of indemnities ruined the Iranian population. This dissatisfaction was used by court circles to incite hatred towards Russian subjects. One of the victims of this hatred was the Russian diplomat A. Griboyedov, who was killed in 1829 in Tehran.

Herat question

By the middle of the XIX century. there is a further aggravation of the contradictions between England and Russia. In the 30s. England took all measures to weaken the strengthened positions of Russia in Iran and to wrest the Caucasus and Transcaucasia from Russia. The aggressive plans of the British concerned not only Iran, they extended to Herat and the Central Asian khanates. Already in the 30s. England, following Iran and Afghanistan, began to turn the Central Asian khanates with Herat into its market. Herat was of paramount strategic importance - the Herat oasis had a surplus of food, and most importantly, it was the starting point for the trade caravan road from Iran through Kandahar to the borders of India. Possessing Herat, the British could also extend their influence to the Central Asian khanates and Khorasan.

The British sought to keep Herat in the weak hands of its Sadozai shahs and prevent it from passing to Iran or joining the Afghan principalities. eastern borders was the Punjab state. In order to prevent the establishment of the British on the outskirts of the Central Asian khanates, Russian diplomacy encouraged Iran to seize Herat, preferring to see this "Key of India" in the hands of the Qajars dependent on Russia.

Iranian rulers in 1833 came out with an army to subjugate the ruler of Herat. After Muhammad Mirza was crowned Shah of Iran in 1835, the struggle between England and Russia for influence in Iran intensified. Wishing to strengthen their position, the British sent a numerous military mission to Iran. However, the advantage turned out to be on the side of Russian diplomacy, which encouraged Iran's campaign against Herat. Therefore, in connection with the new Herat campaign, Anglo-Iranian relations deteriorated sharply.

Soon after the start of the campaign of Iranian troops against Herat in 1836, England broke off diplomatic relations with him. At the same time, an English squadron appeared in the Persian Gulf. Threatening to seize Iranian territories, the British succeeded in lifting the siege of Herat. This was not the only British success. In October 1841, England imposed a new treaty on Iran, under which it received large customs privileges and the right to have its own trading agents in Tabriz, Tehran and Bandar Bushehr.

By the middle of the XIX century. Herat again gained importance as a springboard for British conquests in Central Asia. The rich Herat region also attracted Iran. During the years of the Crimean War, the Shah decided to take advantage of the fact that the British were tied up by the protracted siege of Sevastopol and take Herat. In addition, the Iranian rulers were afraid of the head of the Afghan state, Dost-Mohammed, who concluded a treaty of friendship with England in 1855.

In early 1856, Iranian troops took Herat. In response, England declared war on Iran and sent its fleet into the Persian Gulf. Iran again went to sign an agreement with England. According to the 1857 treaty, England undertook to evacuate its troops from Iranian territory, and Iran - from Herat and the territory of Afghanistan. The Shah of Iran forever renounced all claims to Herat and other Afghan territories and, in the event of a conflict with Afghanistan, undertook to resort to British mediation. Such a quick conclusion of the treaty and the evacuation of British troops was explained by the beginning of a popular uprising in India.

The conflict between Iran (Persia) and the Russian Empire had been brewing since the time of Peter I, however, it was only local in nature, full-fledged hostilities began only in 1804.

The beginning of the war

The Ganja Khanate, which existed in the North Caucasus in the second half of the 18th century, was an independent khanate. He managed to coexist around powerful neighbors, occasionally raiding the Karabakh Khanate and Georgia. After the last raid on Georgia, the Ganja Khanate doomed itself to the end of its existence.

Wanting to ensure the security of controlled Georgia, Russia decided to seize and annex Ganja to its territory. Led by General Tsitsianov, on January 3, 1804, Ganja was taken, its khan was killed, and the Ganja Khanate ceased to exist.

After that, the general moved his troops towards Erivan, which was controlled by Iran, with the desire to also annex it to the Russian Empire. Erivan was famous for its fortress, and could serve as a reliable outpost for subsequent military operations against Persia.

Before reaching Erivan, the Russian army met with the 20,000th army of the Persians, led by the son of Shah Abbas Mirza. Having defeated the Persians three times, Tsitsianov's army laid siege to Erivan, but due to lack of food and ammunition, they had to retreat. From that moment on, the confrontation began. The Shah of Persia officially declared war on Russia on June 10, 1804.

The feat of the Karyagin detachment

Inspired by the retreat of the Russians, the Shah of Persia in 1805 gathers an army of 40 thousand people. On July 9, the 20,000-strong army of Abbas Mirza, moving towards Georgia, stumbled upon a detachment of Colonel Karyagin, numbering 500 people. He had only 2 cannons at his disposal, however, neither numerical superiority nor better weapons broke the spirit of the detachment for 3 weeks, they managed to repel numerous Persian attacks, and when the situation became critical they managed to escape. During the retreat, in order not to leave the cannon to the enemy, the soldier Gavrila Sidorov offered to arrange a "living bridge" across the crevice, and lay down there with his comrades, sacrificing his life. For this feat, all the soldiers received salaries and awards, and a monument was erected to Gavrila Sidorov at the General Staff. After that, Abbas Mirza refused to march on Georgia.

Calm

In 1806, hostilities began between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, and the main forces from the Persian direction were transferred to the war with the Turks. Prior to this, General Tsitsianov managed to annex the Shirvan Khanate, laid siege to Baku and agreed to surrender the city, but during the transfer of the keys he was treacherously killed by a relative of the khan. Baku was taken by General Bulgakov. Relative silence continued until September 1808, when an attempt was again made to take Erivan, but it was unsuccessful. Further, in the Russo-Persian war, there was a lull again, Russia mainly waged war with partisan detachments, paying more attention to the confrontation with the Turks.

Resumption of activity

In 1810, a detachment of Colonel Kotlyarevsky captured the fortress of Migri, crossing the Araks, and the vanguard of the troops of Abbas Mirza was also defeated. In 1812, Napoleon I, and the Persians leaning towards peace, decided to seize the moment and defeat the Russians in the Caucasus. The newly assembled army, led by Abbas Mirza, began to gradually take one fortress after another. First taking Shah-Bulakh, and then Lankaran. The situation was managed to break all the same Kotlyarevsky. At the end of 1812, he defeated the Persians at the Aslanduz ford, after which he went to Lankaran. On January 1, 1813, it was taken, after which the war was stopped, peace negotiations began.

The Napoleonic Wars that tormented Europe, the invasion 1812

year, the subsequent victorious raid of the Russian army across Europe, overshadowed the great battles of the Russian-Iranian war that broke out in 1804

year, when the Russian Empire single-handedly waged two long-term wars in Asia. And both came out victorious.

At the beginning 19

century, the increased military power of the empire made Russian citizenship attractive to small Asian khanates and kingdoms. The voluntary annexation of Eastern Georgia, several Azerbaijani khanates and sultanates to Russia led to the complication of relations with the geopolitical neighbors of the Russian Empire - Iran and Turkey.

In May 1804

In the 18th century, the Shah of Iran, irritated by Russian expansion in Transcaucasia, through his ambassador, presented an ultimatum to the commander-in-chief of the Russian army in Georgia, General Tsitsianov, which contained a demand for the withdrawal of troops from Transcaucasia. A month later, Abbas-Mirza, the militant heir of the khan, led the Iranian troops gathered in the vicinity of Yerevan to storm Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi). The Russian army in Transcaucasia was three times smaller than the Iranians. However, in several oncoming battles, she managed to push the enemy back to Yerevan and laid siege to the city. In September, due to lack of ammunition and food, the siege had to be lifted.

The army returned to Tiflis. Despite the not entirely successful campaign, its morale effect was very strong. During the year, several more khanates voluntarily joined Russia, including Karabakh. Russian garrisons were placed on their territories.

The outbreak of conflict in Europe led to the rapprochement between Napoleonic France, seeking to weaken Russia, and Iran. The Shah hoped, using the support of an influential European state, to oust the Russian neighbor, weakened by a bloody war in the West, from eastern Georgia.

Fighting resumed in the summer 1805

of the year. The Shah's army invaded Karabakh and the environs of Yerevan. Tsitsianov, aware of the multiple numerical superiority of the enemy, decided to act on the defensive, distracting the enemy with amphibious landings involving the Caspian Flotilla.

The successful raids of the Caspian flotilla and the staunch defense of Colonel Koryagin's detachment in Karabakh thwarted the Iranian invasion of Georgia and made it possible for the Russian command to regroup its troops. Having managed to assemble a strong army grouping and seizing the strategic initiative, Tsitsianov laid siege to the fortress of Baku. During negotiations on the surrender of the fortress with the head of the Baku garrison, Mustafa Khan, in February 1806

a Russian general was treacherously killed.

The new commander-in-chief, General Gudovich, had an even harder time than his predecessor. 1806

the year was overshadowed by the start of another Russian-Turkish war. Irreconcilable neighbors Iran and Turkey, thanks to the strong diplomatic pressure of France, concluded a peace treaty. The small Russian army in Transcaucasia had to fight on two fronts.

In June 1806

Russian regiments, together with the allied mountain detachments, captured Derbent without a fight. By the end of the year, Baku, the Cuban Khanate and the entire territory of Dagestan were occupied by the Russian army.

Under the terms of the Tilsit Peace Treaty, Russia and France were nominally allies. However, Napoleon continued to provide assistance to Iran by sending military advisers to the Shah to create a new type of regular army with units of Sarbaz infantrymen. With the active support of France, the production of artillery pieces and the reconstruction of fortresses were launched in Iran.

When in September 1808

year, after the breakdown of the negotiation process, Russian troops tried to storm the fortress of Yerevan modernized by Europeans, they suffered serious losses and retreated to Georgia.

Disillusioned with Napoleon, the Shah of Iran moved closer to Great Britain. England, becoming an enemy of Russia, took the chance to weaken the empire with a long war in Asia and provided Iran with comprehensive support.

V 1810

In the same year, the restless Abbas Mirza began to gather troops in Nakhichevan to capture Karabakh. The Russian command played ahead of the curve. The Jaeger detachment of Colonel Kotlyarovsky stormed the impregnable mountain fortress of Migri, repulsed all attacks of Abbas Mirza, who came to the aid of the garrison, and then turned the enemy troops outnumbered into a stampede with a counterattack.

Abbas Mirza, together with the detachments of the Erivan Khan and the Akhaltsikhe Pasha, tried to take revenge near Akhalkhalaki, but was again defeated.

Fighting resumed in September 1811

of the year. The Iranian Shah's army was reinforced by British supplies. She received 20

thousand new guns and 32

guns.

General Paulucci, who replaced Gudovich, decided to finally drive the Turkish troops out of Transcaucasia, capturing the last Turkish fortress in this region - the city of Akhalkalaki. A consolidated detachment under the command of the brilliant commander Kotlyarovsky, during an hour and a half assault, captured the citadel, capturing its commandant, Izmail Khan. This victory helped M.I. Kutuzov to successfully complete his diplomatic mission in Asia. V 1812

a month before the French invasion in Bucharest, peace was concluded between Russia and Turkey.

The Shah of Iran continued the war alone. autumn 1812

Abbas-Mirza's army captured the Lankaran fortress in the Talysh Khanate. The Iranian army, numbering over 30,000 trained soldiers, camped on the banks of the Araks River. Early morning 19

October she was attacked from the rear by a small detachment (about 2000

huntsmen and Cossacks) Major General Kotlyarovsky, who on the eve walked around it through mountain passes. The Iranians retreated in panic, losing about 10,000 people. The trophies of the Russians were cannons and several Iranian banners with a dedicatory inscription of the English monarch - From the king over the kings, the shah over the shahs. Building on success, in December 1812

General Kotlyarovsky led his consolidated detachment on the offensive against Lankaran. The authority of the Russian commander was so high that the equal Iranian garrison of the Arkevan fortress, which stood in the way of his detachment, did not offer him any resistance and fled, leaving guns and ammunition behind. In the end December Kotlyarovsky's detachment joined the Russian naval garrison he had unblocked in the town of Gamushevan. 1

January 1813

General Kotlyarovsky led his fighters to storm the Lankaran fortress. The fortress was protected by an earth rampart and massive stone walls. Lankaran garrison numbered 4,000 or more 60

guns. The assault began at five o'clock in the morning in complete silence without drumming. Before the assault, the soldiers were warned that there would be no command to retreat under any circumstances. It was not possible to covertly approach the fortress - the garrison opened heavy artillery fire on the advancing columns, preventing them from climbing the walls along the assault ladders. Fighting in the forefront, Kotlyarovsky was wounded in the leg and face. The bullet knocked out the general's right eye. However, the Iranians failed to defend the fortress. When the Russian chasseurs burst onto the walls, the garrison faltered and fled. Enraged by the wounding of their respected commander, the soldiers destroyed all the defenders of the fortress. The thirty-year-old lieutenant general, who received three serious wounds, remained alive, having withstood almost three hundred kilometers of evacuation along mountain paths. However, this was the end of his military career. He retired with the rank of General of Infantry.

spring 1813

In the 1890s, the infantrymen of Colonel Pestel staged a pogrom of Iranian troops near Yerevan. The Shah of Iran hastened to start negotiations for peace. Gulistan peace treaty between Russia and Iran concluded in October 1813

year secured the accession to Russia of several new khanates, including Baku. The Shah recognized the territories of Dagestan and Eastern Georgia as Russian. The exclusive right of the Russian Empire to maintain a military flotilla in the Caspian was also stipulated.