Battle of the paratroopers: the British against the Germans. Parachute Regiment - Airborne Parachute Regiment British paratroopers of World War II

The Parachute Regiment (also called "British Paratroopers"), established by Sir Winston Churchill in 1940, after the end of World War II participated in more than 50 campaigns and deservedly occupies its rightful place among the most prestigious parts of Britain.

With only 370 men, the first British airborne unit was formed first from the personnel of the 2nd detachment. However, its ranks quickly replenished with volunteers, and, once in Tunisia, the paratroopers of the 2nd Airborne Brigade, as the unit began to be called from July 1942, soon earned the Germans the nickname "die roten Teufel" - "red devils".

In 1943, the brigade landed in Sicily; later it became known as the 1st Airborne Division. Meanwhile, the 6th Airborne Division was formed in England, which played the role of a battering ram during the Allied landings in Normandy in June 1944. In August of the same year, the 2nd separate brigade (recruited from the volunteers of the 1st division) was dropped over Provence in order to cut the communications of the German troops. At the end of September, paratroopers of the 1st division, together with the Polish brigade, landed in the Arnhem hell. Then the Red Devils distinguished themselves in Operation Varsity, which paved the way for the Rhine crossing. "

Although the post-war demobilization significantly thinned the British airborne forces, the parachute regiment soldiers continued to defend the honor of the Union Jack flag around the world: paratroopers were deployed in Palestine (until 1947), in Malaysia, fought on the Suez Canal near Port Said (1956) .), Cyprus (1964), Aden (1965) and Bornso. From 1969 to 1972 they were used in a very dubious way in Northern Ireland as internal troops. In 1982, during the Falklands Conflict, after two battalions of the parachute regiment clearly demonstrated to the whole world that the British airborne assault was still worthy of the glory of their famous predecessors, the heroes of Tunisia and Arnsma, they again found themselves in the center of attention and recognition.

British paratroopers, like all British infantry, are equipped with the SA-80 5.56mm combat system, which includes the L85A2 assault rifle ("individual weapon") and the L86A2 light machine gun ("light support weapon"). This weapon has shown itself well on the shooting range, but in practice it turned out that it is quite capricious, does not withstand frequent parachute jumps, and the paratroopers take it with them only on combat operations. To combat enemy armored vehicles, Milan missile launchers are used - a weapon more powerful than that of conventional infantry units.

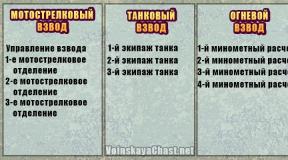

Until 1999, three battalions of the parachute regiment (1st, 2nd and 3rd) belonged to the regular British army, and two more (4th and 10th) belonged to the territorial forces. Two of the three regular battalions of the parachute regiment, on a rotational basis, were part of the 5th Airborne Brigade, where, alternately, they were used as an advanced airborne battalion group and an airborne battalion support group. In 1999, the brigade was disbanded and at the present time the parachute units of Britain are represented by 2 battalions (2nd and 3rd battalions), which make up the Parachute Regiment, which is part of the 16th Air Assault Brigade.

British Airborne Forces glider

Bridge in Arnhem. Operation Market Garden. 1944

British Airborne Forces ( english British Airborne forces ) - A highly mobile elite branch of the Ground Forces of the British Armed Forces, which at different times included military formations, units and subunits of lightly armed infantry, which were intended to deliver air to the enemy's rear and conduct active hostilities in its rear zone.

1. The history of the creation of the British Airborne Forces

1.1. Formation of the first divisions

After the victory in the First World War, the armed forces of Great Britain rested on well-deserved laurels and until the early 30s resembled a real reserve of outdated forms of warfare and in any innovations in this area they were treated with caution and sometimes even hostile. The attempts of the American Brigadier General W. Mitchell, who in 1918 insisted on the early creation of large airborne formations, found even fewer supporters in England than in the United States. A worthy adversary, according to British military theorists, was no longer in Europe. "The war to end all wars" ended with the complete victory of the Entente, and any desire to strengthen the military power of Germany or the USSR was supposed to stifle in the bud by increasing economic pressure. Under these conditions, the British believed that there was no need to change the time-honored structure of the armed forces, and even more so to introduce such extravagant ideas as the landing of soldiers from the air.

But, the irony of fate after 4 years created doubts about the correctness of these views. The British experienced a marriage in the experience of using landing troops only during the conflict in Iraq. After receiving the mandate to manage this territory, the formerly part of the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire actually turned it into its semi-colony. Since 1920, lively hostilities have begun in the country between British troops and the local national liberation movement. In order to compensate for the lack of mobility of their ground forces in the fight against the cavalry detachments of the rebels, the British transferred a significant number of combat aircraft to Iraq from Egypt, including two military transport squadrons. Under the leadership of Air Vice Marshal John Salmond, a special tactic was developed for the Air Force's actions with their participation in actions to "pacify" the rebellious territories. Since October, Air Force units have been actively involved in suppressing the uprising.

Germany's triumphant use of its parachute units during fleeting campaigns in Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Holland in 1940 did not convince the orthodox British military of the need to create similar units of their own. Only on June 22, 1940, almost after the defeat of France, Prime Minister Churchill gave the order to begin the formation of various special-purpose units, including the parachute corps.

1.2. Parachutists of the British Empire

In addition to the British units themselves, the British VAT was supplemented by the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion (eng. 1st Canadian Parachute Battaillon ). The battalion was formed on July 1, 1942, and in August 85 officers, sergeants and soldiers from its composition arrived in Ringuei for special training. Soon, Shiloh established a Canadian parachute training center. Meanwhile, the battalion, which had completed its training, became part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade of the 6th Airborne Division and participated in Operation Overlord and subsequent battles in Europe (including the Ardennes on Christmas Day 1944).

In March 1945, the Canadians participated in Operation Varsity (landing across the Rhine), and then the battalion was withdrawn to its homeland and disbanded in September.

Following the first battalion, the Canadians manned three more. To this were later added one Australian and one South African battalion, which allowed the British, together with the staff of the 44th Indian Airborne Division, to bring the total number of VAT to 80,000 people.

1.3. Indian parachutists

The first detachment of paratroopers in India was formed on May 15, 1941. However, the creation of the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade was officially announced only in October 1941. Its recruitment was carried out in Delhi, while a training center called "Airlanding School" ("Airborne School") was organized at an air base in the New Delhi area. The brigade consisted of the 151st British, 152nd Indian and 153rd Gurksky parachute battalions. The first training jumps took place on October 15 in Karachi, and in February 1942, the first brigade exercises for the landing of airborne assault were held.

The brigade received its baptism of fire back in 1942: small groups of paratroopers made the first parachute jumps three times in combat conditions. In July, a company of an Indian battalion was thrown into Sindh during an unsuccessful operation to suppress a mutiny of one of the local tribes. In the same month, a reconnaissance group of 11 people landed near Myichin (Burma territory) with the task of collecting data on the Japanese forces stationed there. In August, 11 more people landed in Burma, in the area of \u200b\u200bFort Hertz, to prepare a small airfield to receive gliders with groups of shinditives.

In March 1944, the 50th Brigade was transferred to the command of the 23rd Infantry Division with the task of preventing the Japanese offensive in the northeastern regions of India. Fighting there continued until July, and the brigade brilliantly proved itself in defensive battles at Imphal and Kohimoyu. At the same time, the forty-fourth Indian mixed traffic police was created, which was later reinforced by the 77th Indian parachute brigade.

Immediately before the end of the war, the 44th division was transferred to a new base in Karachi, renaming it 2 in the Indian traffic police.

1.4. Iraqi paratroopers

In addition to the Hindus, Sikhs and Gurks, who fought on different fronts for the glory of Great Britain, the British also attracted the Arabs under their banners. Even Iraq, which was not part of the empire, but in 1941, turned into an arena of battles between Pro-German rebels and the British Expeditionary Force, fielded its contingent. In 1942, one hundred and fifty officers and sergeants of the Royal Iraqi Army, undergoing special training under the guidance of British advisers, completed the newly created 156th Parachute Battalion. Then he was included in the 11th British parachute battalion, "demoted" in the parachute company. In this capacity, the Arabs took part in the battles in Italy and landings on the islands of the Aegean Sea (July 1943).

Six months later, the first parachute unit in Iraq was disbanded as unnecessary.

2. Participation in combat operations

2.1. First steps

2.3. Normandy

When preparing before landing in Normandy, the 1st and 6th divisions were called into the 1st British Airborne Corps (eng. 1st British Airborne Corps ), having confirmed at once with the 18th Airborne Corps of the US Army the First Allied Airborne Army (eng. First allied airborne army ) under the command of the American Lieutenant General Luis H. Brereton.

2.3.1. Mervilska battery

In Veresna 1944, the 1st traffic police, which was commanded by Major General Richard C. Urquhart (eng. Urquhart ), She took part in one of the largest and most unsuccessful airborne operations of the Second World War, called Arnemskoy or Dutch (codenamed "Market Garden"). On the first day, 5,700 British paratroopers (50% of the personnel of the 1st Division, together with its headquarters) were to land from the airfields of southern England. The next day, this figure was supposed to be 100%. Despite all the pressure of the parachutists, the assault was unsuccessful. Therefore, in general, the operation was defeated, due to the fact that the First Airborne Division was unable to capture and hold the bridges near the Dutch city of Arnhem, despite the fact that in general they held out much longer than planned. Units of the XXX British Army Corps were unable to break through the defenses in a certain area, and most of the forces of the 1st Airborne Division (about 7,000 paratroopers) were captured.

4.3. Lieutenant John Grayburn - 1944

In the course of battles for the Arnhem region, Lieutenant Greyburn keruvov with his people stretching out three dib, heroically settling the positions near the bridge, and I want two wounds to be seen and evacuated from the battlefield. Yogo special manhood, leader's quality and showcase allowed the paratroopers to utrimuvati mest shonaidovshe. A husband's officer zaginuv at the rest of the nich tsikh battles.

4.4. Flight Lieutenant David Lord - 1944major, we will injure you and drag them over from the safe mission. To navigate the wounded, having continued the evacuation of a special warehouse from a damaged armored personnel carrier, I do not respect the city of warriors' sacks, and saved the life of three choloviks.

4.7. Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Jones - 1982

Colonel Herbert Jones, Commander of the 2nd Airborne Battalion, having blocked the attack of the paratroopers during the battle for Darwin and Gus-Grin at the Falklands War 1982. Win attacking the position of the Argentine gunmetal rozrahunku with contempt to the power of safety and the bulwark of the wounds of the docks without falling into the guardian position.

4.8. Sergeant Ian McKay - 1982

Sergeant McKay, serviceman of the 3rd battalion of the parachute regiment, having witnessed a heroic feat if the platoon commander was injured at the move of the Falkland War to 1982 rock. Having repaired the wounded commander, the sergeant scrutinized the ukrittya and smithely attacked the enemy's position with a heavy fire, like 2 paratroopers were wounded and one shot, McKay threw hand grenades at the enemy. The attack of a man's parachutist, who sacrificed his living lives, sent the Argentines from the head forces to the platoon, who wondered if the position was assigned.

See also

5. Video

6. Footnotes

Literature

- Lee E. Air Power - M .: Foreign Literature Publishing House, 1958

- Nenakhov Yu. Yu.: Airborne troops in the second world war. - Minsk: Literature, 1998. - 480 pp. - (Encyclopedia of military art). ...

- Nenakhov Y. Special Forces in the Second World War. - Minsk: Harvest, Moscow: ACT, 2000.

- J.M. Gavin Airborne Warfare AST Publishing House, M., 2003

Parachutists of the British Empire

After the deployment of the formation of airborne troops in the metropolis, similar activities began in British India, a colony with the largest and most efficient armed forces in the empire.

The commander-in-chief of the Anglo-Indian troops, General Sir Robert Cassels (Cassels), in October 1940 ordered the creation of parachute units. The three newly formed battalions were to include volunteers from among the representatives of indigenous nationalities, specially selected from the personnel of the British, Indian and Gurkish units stationed in Asia. In December, Cassels ordered the manning of the airborne brigade, although London did not immediately sanction this step, citing a lack of special equipment and transport aircraft (some of the parachutes allocated for the Indian army were confiscated for their needs by David Stirling's "L detachment" sent to the Middle East - the forerunner of CAC). The War Department supported Cassels' plan only in June 1941, and then on condition that one of the battalions would be fully manned by the British.

In fact, the first paratrooper detachment was formed on May 15, 1941. However, the creation of the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade was officially announced only in October 1941. Its recruitment was carried out in Delhi, while a training center called "Airlanding School" ("Airborne School") was organized at Willington Air Base (New Delhi area). The brigade consisted of the 151st British, 152nd Indian and 153rd Gurk parachute battalions. Most of the officer and sergeant positions (including junior specialists), of course, were occupied by Europeans. The first training jumps took place on October 15 near Karachi, and in February of the following year, the first brigade exercises for the landing of airborne troops were held. By this time, the problems with the supply of special equipment had already been largely overcome, and almost all personnel were constantly training on the ground. Thus, India unexpectedly became one of the oldest "airborne" powers on earth.

The brigade received its baptism of fire back in 1942: small groups of paratroopers made the first parachute jumps in combat conditions three times. In July, a company of an Indian battalion was thrown into Sindh during an unsuccessful operation to suppress a mutiny of one of the local tribes. In the same month, a reconnaissance group of 11 people landed near Myichin (Burma territory) with the task of collecting data on the Japanese forces stationed there. In August, 11 more people landed in Burma, in the area of \u200b\u200bFort Herz, to prepare a small airfield to receive gliders with groups of Shindites.

In the fall of 1942, a period of change began for the brigade. In October, the 151st British battalion was withdrawn from its composition, which was transferred to the Middle East. In the same month, the Airborne School was renamed the Parachute Training School and relocated to Shaklala.

It was followed by the redeployment of the entire brigade - its units were stationed in the town of Campbellpur (about 50 miles from Shaklala). At the beginning of the next year, instead of the British battalion that had departed for the Mediterranean, a battalion of Gurks entered the brigade. At the same time, a plan appeared on the basis of the 50th and one of the British parachute brigades of the 9th Indian Airborne Division. It was supposed to be used in battles in the Middle East or in Europe, but the absence of a "free" British brigade delayed this process at the stage of organizing headquarters structures.

In March 1944, the 50th Brigade was transferred to the command of the 23rd Infantry Division with the task of preventing the Japanese offensive in the northeastern regions of India. Fighting there continued until July, and the brigade, which over time was again granted operational independence, brilliantly proved itself in defensive battles near Imphal and Kohima. At the same time, the 9th division, which had not yet completed its formation, was renamed the 44th Indian Airborne Division (the headquarters of the 44th Armored Division, previously disbanded due to the uselessness of the 44th Armored Division) was transferred to the formation. It consisted of: 14th Infantry Brigade - British 2nd Infantry Battalion "Black Watch", Indian 4th Rajputana Rifle (Rajputana rifles) and 6 / 16th Punjab Infantry (Punjab regiment), as well as the 50th a parachute brigade, withdrawn to the rear and stationed in Rawalpindi. The 14th brigade was supposed to be used as an air-landing on gliders. In January 1945, the division was reinforced with a new 77th Indian Parachute Brigade. The new brigade was formed on the basis of the allocated units of the 50th brigade and shindite units. It consisted of: the 15th British, 2nd Gurk and 4th Indian parachute battalions, as well as the British 44th separate company of Pathfinders (formed according to the American model). By the beginning of 1945, the 16th English, 1st Indian and 3rd Gurk battalions continued to be listed in the 50th brigade. In addition to these units and the 14th Airborne Brigade, the division included the 44th Indian Airborne Reconnaissance Battalion (staffed by Sikhs) and support units: four engineering battalions plus separate units (communications, four medical, a repair fleet, a supply company and three motor transport companies).

The Indian Parachute Regiment, created with the sanction of the British government in December 1944, took part in the formation, training and supply of the Indian and Gurkian battalions.In a system modeled on the British, the regiment served as a base and a military headquarters engaged in recruiting and training reinforcements exclusively from the number of indigenous peoples. Relying on the cadres of two Gurkish and one Indian battalions from the 50th brigade, the headquarters formed two new parachute battalions for the 50th and 77th brigades included in the 44th division, which were supplemented (according to London's requirements) with one British battalion each.

The natural conditions of the Far East did not facilitate the conduct of large-scale airborne operations using hundreds of aircraft and gliders, just like in Europe. During the Second World War, mainly small groups operated in this theater of operations, as a rule, a force of up to a company, or even a platoon. In the first half of 1945, within the framework of Operation Dracula, the British headquarters in India planned to conduct a landing operation in the area of \u200b\u200bthe capital of Burma, Rangoon (located 35 kilometers from the mouth of the Rangoon River). The river was heavily mined by both the Japanese and allied aviation. Therefore, in order to provide cover for the minesweepers, and then for the landing barges crossing the river, it was decided to seize a bridgehead on its western bank with the help of an air assault. The most important point dominating the mouth was the height of Ele-fant-Point. The task to master it was entrusted to a special-purpose battalion, formed from volunteers (from the personnel of the 50th brigade) and reinforced by medical, communications and sapper units.

The last preparations for the operation unfolded on April 29 in Akyaba, where a reserve detachment (200 people) arrived, formed from the servicemen of the 1st Indian, 2nd and 3rd Gurk parachute battalions. The delivery of the landing force to the target was to be provided by the US Air Force aircraft, but due to the insufficient training of American pilots, this task was assigned to the 435th and 436th Canadian squadrons. The landing was planned to be carried out in two stages. The first two vehicles threw out the pathfinders and sappers needed to prepare the site, the second wave included eight aircraft with the main landing force.

On May 1, at 3.10 am, the operation began. As intelligence reported, there were no enemy units in the landing zone, but during an allied air raid on the Elephant Point area, attack aircraft mistakenly attacked one of the paratrooper units (about 40 people were injured). At half past three in the afternoon, the main forces were dropped: after half an hour, the Indian paratroopers captured the entire height, destroying the only Japanese bunker with a flamethrower. At the same time, Allied aircraft neutralized the Japanese ships at the mouth of Rangoon, ensuring the possibility of supplying supplies. The battalion was withdrawn to the liberated Burmese capital on May 3, and before returning to India on May 17, it was once again parachuted into the Japanese position - near Tohai. Immediately before the end of the war, the 44th division was transferred to a new base in Karachi, renaming it the 2nd Indian Airborne Division.

In addition to Hindus, Sikhs and Gurks, who fought on different fronts for the glory of Great Britain, the British also attracted Arabs under their banners. Even Iraq, which was not part of the empire, and in 1941 turned into an arena of battles between pro-German rebels and the British expeditionary force, fielded its contingent. In 1942, one hundred and fifty officers and sergeants of the Royal Iraqi Army, who underwent special training under the guidance of British advisers, completed the newly created 156th Parachute Battalion. This small military unit, nominally not subordinate to the British command in the Middle East in accordance with the Anglo-Iraqi treaty, was stationed at the Habbaniya airfield. Then she was included in the 11th British Parachute Battalion, “demoted” to a company. In this capacity, the Arabs participated in battles in Italy and in landings on the islands of the Aegean Sea (July 1943). Six months later, the first parachute unit in Iraq was disbanded as unnecessary.

A uniform

Indian paratroopers wore the usual English or Indian field uniform and chestnut berets. Items of special equipment and uniforms - "Denison blouses", airborne steel helmets, trousers, etc. - were not common in the colonial airborne forces. The Indians jumped in special khaki-colored cloth hoods covering the head, and in battle they wore ordinary infantry helmets. Items of Indian colonial uniforms, used since the First World War, were also almost never found among paratroopers: since 1943, the British began to dress Hindus and Sikhs in ordinary "battle-dresses".

Along with berets in the field, they often wore knitted "fishing" hats, similar to those used in commando units. Parachutes - British Hotspur Mk II or other samples supplied from the metropolis. Paratroopers from the Gurk battalions hung their famous curved knives - kukri from the back on their belts. The kukri is equipped with a brown wooden handle in the form of a cylinder expanding towards the heel. The handle is finished in brass, in the form of rings and dowels. The total length of the weapon is 460 mm, the blade is about 40 centimeters, the thickness of the butt is about 10 mm. The single-edged blade has a reverse bend and expands in the lower third: this gives the kukri a huge impact. The triangular section of the blade symbolizes the Hindu Trimurti - the unity of the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. Knives made by various manufacturers had different blade curvatures, variations in finishes and structural elements. On the heel of the blade, ciphers, symbols of the supplier plant, date of manufacture, batch numbers, etc. were applied (in the 40s, knives made in the First World War were used in the Gurkian units). Kukri is worn in a sheath of wood covered with brown leather with a brass tip. The scabbard has compartments for two small knives: one is used for cutting, the other has a blunt blade and is used to strike sparks when lighting a fire. At the same time, the handles of two knives stick out from the scabbard. The scabbard with the help of a system of straps is suspended from the waist belt at the back in an upright position with the handle to the right hand (belt loops are connected to a leather clamp into which the scabbard is threaded; the clamp is equipped with lacing). All suspension and lacing details are brown leather.

The golden emblem of the Royal Airborne Forces was pinned to the left side of the beret, and a British paratrooper qualification badge (wings and an open parachute) was sewn on the upper part of the right sleeve.

It should be noted that the Indian and Gurkish forces used a special rank system for privates, sergeants and officers of indigenous nationalities. Part of the "native" officer corps, which passed the Royal Attestation Commission, wore the usual British insignia on their shoulder straps. However, the vast majority of commanders were officially called "Viceroy's Commissioned Officers" (VCO) - "officers certified by the Viceroy of India." Their status was lower, so special ranks were traditionally used for them: Jemadar, Subedar and Subedar Major (corresponding to English from lieutenant to captain). Since October 1942, all Indian VCOs wore one or three small silvery quadrangular "knobs" on their shoulder straps, pinned to the transverse stripes of braid: red, yellow, red. Corporals and a sergeant in the Indian-Gurkish units were called lance-nike, nike and havildar; the private was called the sepoy. Their white or green (in rifle battalions) sleeve patches were similar to the British ones, but were simpler and cheaper, without embossed sewing.

From the book of the Aztecs. Warlike subjects of Montezuma author Soustelle JacquesReligion of the Empire The young civilization of the Aztecs barely reached its heyday, when the invasion of Europeans interrupted its growth, its development, and the deepening of its religious philosophy. As it was on the eve of the catastrophe, or as it lives in our understanding

From the book Firearms of the XIX-XX centuries [From mitraleza to “Big Bertha” (liters)] author Coggins JackEmpire Builders Empire building was inextricably linked with the fighting of the British army, which fell on much of the 19th century. Except for Crimea, not a single British unit set foot on the continent from the time of the Battle of Waterloo until 1914.

From the book Aphorisms of Britain. Volume 2 author Barsov Sergei BorisovichLittle things about British life If you have a dog, there is no need to bark yourself. Proverb At home, every dog \u200b\u200bfeels like a lion. Proverb At its doors every dog \u200b\u200bis brave. Proverb A good dog doesn't spare a good bone. Proverb The best gift is what is

From the book Admiral Oktyabrsky against Mussolini author Shirokorad Alexander BorisovichCHAPTER 5. PARACHUTISTS OVER SEVASTOPOL Since the mid-1960s, our historians, memoirists and writers began to describe the events of the first hours of the Great Patriotic War with great zeal. Stalin was asleep, and so was Beria. Only here is one People's Commissar of the Navy N.G. Kuznetsov ordered in time

From the book Afghan War of Stalin. Battle of Central Asia author Tikhonov Yuri NikolaevichChapter 5. A New Threat to British India The actual recipient of the German plans to strike at India through Afghanistan was Soviet Russia, which needed to weaken its worst enemy - Great Britain at any cost. As soon as January 1919 was

From the book by John Lennon. All the secrets of the Beatles author Makariev Artur ValerianovichChapter 22. New blood in the "independent" strip of British India The capture of Kabul inspired the Pashtuns of British India. A prominent Pashtun politician Abdul Ghaffar Khan wrote on this occasion: “This is an example for you, Pashtuns of the border, how to stop your petty quarrels,

From the book Defeat in the West. Defeat of Nazi troops on the Western Front by Shulman Milton From the book British Empire author Bespalova Natalia YurievnaDocument # 10: Letter from the British Intelligence Representative in Moscow, Colonel Hill MOST SECRET.FROM: Colonel G. A. Hill, D. S. O., TO: Colonel Ossipov.Moscow, 11th. December, 1943. Re: Bhagat Ram. As you are aware, the Government of India has granted, a safe-conduct to both Rasmuss and. Witzel of the German Legation in Kabul, who have teen recalled, to Germany by their Government. While their traveling arrangements will be

From the book In Search of Eldorado author Medvedev Ivan AnatolievichLondon. Russian department of British intelligence MI-6. July 1969 In July, the Beatles worked actively on their new and last album. At the recording and rehearsals, they, as in the old days, were united, there was no one superfluous in the studio, they worked harmoniously, knowing full well that

From the book Adventure Archipelago author Medvedev Ivan AnatolievichCHAPTER 27 PARACHUTISTS AND DIVERSANTS Infantry and tank divisions were not alone in having difficulty in carrying out their combat missions. Additional formations brought into operation for combat operations in the American rear have their own problems. These formations are usually

From the book The Darwin Prize. Evolution in action author Northcutt WendyLieutenant in the British Army When the war broke out in August 1914, Lawrence was in Oxford, working on materials he had collected during the expedition to Sinai. He finished work pretty quickly, after which he tried to volunteer for the army, but at first he was

From the author's bookThe decline of the empire In captivity, Atahualpa quickly realized why the white people came to his land. For his release, he offered a ransom: fill the room in which he was kept with gold up to the level of an arm extended above his head. Pizarro agreed, and from all corners of the empire

From the author's bookOn the outskirts of the empire One morning, a large detachment of 500 rebels appeared at an outpost with a tiny garrison of 20 soldiers with one cannon. The fight lasted until noon. When gunpowder came out, Sergeant Efremov with several soldiers tried to break into

From the author's bookBaron of the Empire During the three years of the corsair's war, Surkuf amassed a fortune - two million francs. He returned to his homeland, bought a castle in Saint-Malo and married an aristocrat. For four years, the corsair lived quietly and peacefully with his family, until the news of the defeat came

From the author's bookDarwin Prize: Yosemite Parachutists Confirmed by the Darwin Commission October 22, 1999, California It's like jumping off a cliff In Yosemite National Reserve, skydiving from majestic cliffs is prohibited because it is life-threatening. But

From the author's bookDarwin Prize: Yosemite Parachutists Confirmed by the Darwin Commission On January 1, 2000, Nevada Tod made a name for itself in history by becoming the first victim of the Las Vegas Millennium Celebration. A few minutes before New Years, a 26-year-old Stanford graduate climbed onto

July 1943. The allies are advancing through the territory of Sicily, pushing the enemy to the north. British generals begin the implementation of a plan to encircle the Italian-German troops so that they cannot redeploy to mainland Italy. On the night of July 13-14, units of the 1st parachute brigade disembark south of the port of Catania in order to capture the strategically important Primosole bridge on the Simeto River, cut off the enemy's path to retreat and facilitate the advance of the 50th Infantry Division. To counteract the landing, the German command throws units of the 1st parachute division to the bridge. So the battle of British and German paratroopers began ...

Target - Sicily

After the surrender of the Italian-German troops in North Africa, held on May 13, 1943, the Allies decided to continue active operations in the Mediterranean region: to land troops in Italy and withdraw it from the game. The first target for the attack was the island of Sicily, on which it was planned to land units of the US 7th Army, Lieutenant General George Patton and the British 8th Army, General Bernard Montgomery. "The first step is to capture a bridgehead in a convenient area and then conduct combat operations from it," - so Montgomery outlined the goals of the future operation. The new operation was codenamed "Husky". The Americans were to create a bridgehead in the southwestern part of the island (on the shores of Gela Bay), the British in its southeastern part.

The allies had a numerical advantage over the enemy - 470,000 people, over 600 tanks and self-propelled guns, 1,800 guns and mortars, 1,700 aircraft. At the same time, the Italian-German troops under the command of General Alfredo Guzzoni and Field Marshal Albert Kesselring were able to deploy over 320,000 soldiers and officers, less than 200 tanks and assault guns, 300-350 guns and mortars, more than 600 aircraft. Do not forget that the Allies had an overwhelming advantage at sea: 2,590 ships took part in the landing operation.

On the night of July 9-10, the Allies carried out an airborne assault on the island, and on July 10, an amphibious assault followed - Operation Husky began. The Germans were unable to throw the enemy into the sea and retreated to the north of Sicily with battles. If in the early days the advance of the units of the 7th and 8th armies proceeded rapidly, in the future the enemy began to offer fierce resistance, especially in the British sector of the offensive. Unlike the coast, the mountainous terrain of Central and Northern Sicily, as well as the underdeveloped road network, favored the actions of the defenders - the Italian-German troops turned villages into strong points, and artillery batteries were located on the hills. On July 10, the 5th British Infantry Division from the 13th Corps (corps commander - Major General Horatio Barney-Ficklin) reached the village of Kassabila (south of Syracuse). Parts of the 13th corps were heading towards Augusta, but not far from Priola they were stopped by the powerful resistance of the units by the battle group "Schmalz" under the command of Colonel Wilhelm Schmalz (units of the Luftwaffe tank division "Hermann Goering" and the 15th Panzergrenadier division, including several "Tigers") ...

Strategic bridge

Montgomery intended to prevent the evacuation of Italian-German troops from Sicily through the Strait of Messina, relying solely on the forces of the 8th Army. First of all, the British had to capture the reinforced concrete Primosole bridge, over 120 m long, connecting the banks of the Simeto River and located seven miles south of the port of Catania. The capture of the bridge was necessary for the successful advance of parts of the 13th corps to the north and the capture of Catania.

Primosole bridge

It was originally planned that the strategic object would be captured by the soldiers of the 50th Infantry Division (commander - Major General Sydney Kirkman) with the support of the tanks of the 4th armored brigade (commander - Brigadier John Cecil Carrie). But later the plan changed, and units of the 1st Airborne Division of Major General George Hopkinson, namely the 1st Parachute Brigade (commanded by Brigadier Gerald William Lutbury), were instructed to seize the bridge. The soldiers of the division were not newcomers - they managed to take part in the Brunewald raid of 1942, the battles for the Norwegian hydroelectric power station Vemork, the Tunisian campaign, as well as the landing at Syracuse on the night of July 9-10, 1943. The Primosole Bridge was to be occupied by the 1st parachute battalion of Lieutenant Colonel Alastair Pearson, and the 3rd (commander - Lt. Col. Eric Yeldman) and 2nd (commander - Lt. Col. John Frost) battalions were ordered to cover the bridge from the north and south, respectively.

Lieutenant Colonel Alastair Pearson

Lieutenant Colonel Alastair Pearson

Source - pegasusarchive.org

The parachute battalion commanders were experienced officers and had high awards - Lt. Col. Frost received the Military Cross for the Brunewald raid, and Lt. Col. Pearson received the Military Cross and two Distinguished Service Orders for the Tunisian campaign.

Lieutenant Colonel John Frost

Lieutenant Colonel John Frost

Source - paradata.org.uk

To aid the paratroopers, the 3rd Commando Squad, Lt. Col. John Darnford-Slater, was to take over the Malati Bridge on the Lintini River ten miles south of Primosole Bridge. The British were opposed by units of the Hermann Goering division (commanded by Major General Paul Konrath) and the 15th Panzergrenadier Division (commanded by Major General Eberhard Rodt). In addition, Field Marshal Kesselring decided to transfer parts of the 1st Parachute Division (commanded by Major General Richard Heidrich) to Catania.

German parachutists. Sicily, July 1943

German parachutists. Sicily, July 1943

Source - pegasusarchive.org

Due to a lack of vehicles, Heidrich could not send the entire division at once and first transferred the 3rd Parachute Regiment (commanded by Colonel Ludwig Heilman), the 1st Machine Gun Battalion (commanded by Major Werner Schmidt), signalmen and three anti-tank platoons. On July 12, at about 18:15, German paratroopers from the 3rd regiment (1400 people) landed in the fields near Catania.

Colonel Ludwig Heilmann

Colonel Ludwig Heilmann

Source - specialcamp11.co.uk

The American fighters were unable to intercept the He.111 transports carrying the assault force, as they ran out of fuel (according to American pilots). One of the German battalions was deployed west of the city of Catania, two others were located on the approaches to the Malati bridge. The next morning, units of the 1st machine-gun battalion arrived in Catania, the allied air force attacked the Catania airfield, as a result of which two Me.321 gliders were destroyed, which contained the lion's share of the equipment and ammunition of anti-tank platoons. Thus, the German paratroopers were left with a very meager arsenal of anti-tank weapons. Colonel Heilman understood that if the Allies successfully landed on the Simeto River, the German units located south of it would be surrounded. Therefore, he ordered the commander of the 1st battalion, Hauptmann Otto Laun, to go with his soldiers to the Primosole bridge. He did so, placing his paratroopers two kilometers south of the bridge in an orange grove that provided a good disguise.

Unsuccessful landing

The operation to capture the bridge, codenamed "Fastian", started on July 13, 1943, when at about 20:00 105 C-47 Dakota transport aircraft and 11 Albemarleys AW41 took off from the airfields in North Africa. there were over 1,856 paratroopers of the 1st parachute brigade. Nineteen gliders transported military equipment and ammunition (including ten six-pound guns and 18 jeeps), as well as 77 gunners. From the very beginning of the operation, the British had problems - the allied air defense units mistook the aircraft for German and opened fire on it, and when they reached Sicily, the planes came under fire from Italian anti-aircraft guns. As a result, some of the gliders were damaged and were forced to return, several more cars were killed. Many transport aircraft were also damaged and returned to airfields with 30% of the paratroopers.

At about 22:00, the British began the landing, and then the soldiers of the 1st machine-gun battalion organized a "warm welcome" to them. At first, the Germans mistook gliders for reinforcements, but when signal flares were fired, Heilman's fighters made sure that the enemy was landing, and opened a hurricane of fire from machine guns and several anti-aircraft guns. Several British aircraft were hit and crashed into the field. Later this battle was described by German Lieutenant Martin Pöppel:

“Burning planes fell on fields full of straw and lit up the entire battlefield. Our machine guns did not stop. "

Many British paratroopers had to jump out of burning cars under fire, more than 70 paratroopers were captured immediately after landing. The British had two huge problems - first, almost all radios were lost, and, as Lutbury wrote, "There was no connection with any of the battalions, and no one knew what happened."... Secondly, the planes lost their course, most of them dropped troops at a distance of 20–32 km from the object (some groups ended up at Mount Etna), and only 30 aircraft landed about 300 soldiers in the right place. The situation with the landing of artillery, which was made on July 14, was not in the best way - only four guns reached the designated point. The only success at the initial stage of Operation Fastian was that the Italian units at the bridge fled or surrendered without resistance.

On July 14, at 2:15 am, fifty soldiers of the 1st battalion, led by Captain Ran, captured the Primosole bridge and four pillboxes (two at the northern end of the bridge, and two at the southern end). In the pillboxes, the British found Italian Breda light machine guns and many cartridges for them. Two pillboxes at the northern end of the bridge were not defended by anyone, the capture of the "southern" pillboxes was described by Lieutenant Richard Bingley:

“At the southern end of the bridge, we met an enemy patrol of four Italians. Paratrooper Adams killed two of them at once. Our soldier threw Gamon's hand grenade at one of the pillboxes. Soon, 18 Italians surrendered. The fight was fleeting. I was wounded in the right shoulder. "

At 3:45 am, the paratroopers noticed a light tank, an armored car and three trucks on the road leading to the bridge. The gunners fired a shell at the tank, and the parachutists threw grenades at the cars. Lieutenant Bingley said two trucks were carrying gasoline. The first car was destroyed by Gamon's grenade, thrown by Corporal Curtiss - 22 Italian soldiers died in a terrible death due to fuel ignition. At about 5:00, the British stopped a German truck towing the cannon - the soldiers riding on it threw two grenades in the direction of the parachutists and fled, leaving the cannon behind. Shortly thereafter, British sappers managed to clear the bridge.

Operation Fastian scheme

Operation Fastian scheme

Source - Simmons M. Battles for the Bridges // WWII Quarterly 2013-Spring (Vol.4 No.3)

Without communication and ammunition

The parachutists found two radios in the pillboxes, managed to inform the headquarters of the 4th armored brigade that the bridge had been taken under control, but after an hour the connection was lost. The bridge was guarded by about 120 fighters from the 1st battalion, armed with three mortars, a Vickers machine gun, three PIAT anti-tank grenade launchers, not counting small arms and grenades. In addition, the paratroopers had at their disposal a working six-pound cannon (two more guns needed repair), as well as two 50-mm Italian guns and a 75-mm German cannon. Not far from the bridge there were two platoons of the 3rd battalion, and the soldiers of the 2nd battalion were able to take control of the hills southwest of the bridge in time, capturing more than a hundred Italian soldiers. In total, 283 soldiers and 12 officers from the 1st brigade gathered in the area of \u200b\u200bthe Primosole bridge.

At dawn on July 14, the Germans learned that the bridge had been captured by the enemy. To clarify the situation, a reconnaissance group of Hauptmann Franz Shtangenberg (20 people in two trucks) was sent there. Approaching the bridge at a distance of just over 2 km, the group was fired upon by the British from cannons, after which the Hauptmann returned to Catania and began to gather forces for a counterattack. He managed to collect over 350 people, including cooks, mechanics and 150 soldiers from the communications company under the command of Hauptmann Erich Fassl. As for artillery, the Germans could use a 50 mm Italian cannon and three 88 mm anti-aircraft guns.

Counterattacks by German paratroopers

In the afternoon, the Germans began shelling the British with anti-aircraft guns, as a result of which several paratroopers were injured. According to the testimony of the British, at about 13:00 they were attacked by several Me.110 fighters. At 13:10 the Germans launched the first attack - Shtangenberg's group struck the northern end of the bridge from the right flank, the signalmen from the left. Unable to fight for a long time due to a meager supply of ammunition, the British retreated to the southern end of the bridge.

While the battle for the bridge was underway, German paratroopers from the 1st Machine Gun Battalion attacked the British from the 2nd Battalion stationed in the hills. Corporal Neville Ashley used the Bren light machine gun to hold back the enemy's advance, while a group of soldiers led by Lieutenant Peter Barry suppressed the German machine gun point. The Germans opened fire from heavy machine guns and mortars, and the British retreated, unable to adequately "answer" them.

German parachutists are firing from a machine gun. Sicily, July 1943

German parachutists are firing from a machine gun. Sicily, July 1943

Source - barriebarnes.com

At a critical moment, Lieutenant Colonel Frost was able to locate an intact radio and call in artillery fire from the light cruisers Newfoundland and Mavritius. Heavy shelling from naval guns forced the Germans to retreat (according to British data, they lost more than twenty people killed and wounded). The British took up positions in the hills again. In battle, Captain Stanley Panther distinguished himself - together with three soldiers, he suppressed an enemy machine gun, then captured a light howitzer and fired several shells from it at the enemy. For his courage, the Panthers were awarded the Military Cross.

If Frost's group was able to hold their ground, then for Lieutenant Colonel Pearson's people, the situation became more complicated. After 15:00, the Germans, under cover of artillery and machine guns, hiding behind bushes and trees, again attacked the bridge from the north side, and Pearson ordered his fighters to retreat to the southern bank of the river. It is known that on the afternoon of July 14, the British expected their tanks to appear, but this did not happen. The crew of the six-pound gun managed to smash the pillbox, which the Germans occupied on the northern bank, having used up almost all the ammunition. According to the British, the Germans attacked with the support of a self-propelled gun, but did not dare to break through the bridge, fearing to fall under its fire. Shtangenberg acted wisely - instead of attacking the bridge head-on, he ordered his soldiers to swim in another place, bypass the enemy and strike him from the rear.

Germans recapture the bridge

Lieutenant Colonel Pearson ordered his soldiers to retreat to the hills to the south and join up with Frost's group. The retreat was covered by several groups - Lance Corporal Alfred Osborne, a participant in the battles for Primosole, claimed that the remaining soldiers had only a few cartridges for the Anfield rifles. In the battle at the bridge, 27 British paratroopers were killed and over 70 were injured. Medical corporal Stanley Tynan provided tremendous assistance in the evacuation of the wounded - he evacuated the wounded under shelling, for which he was awarded the Military Medal.

Destroyed pillbox near the Primosole bridge

Destroyed pillbox near the Primosole bridge

Source - pegasusarchive.org

Lance Corporal Osborne covered the retreat, sitting in a bunker and firing from a light machine gun. Soon after he left his position, several shells fired by a German assault gun (according to another version, an 88-mm anti-aircraft gun) hit the pillbox.

After 18:00, a group of Hauptmann Laun approached the bridge from the south, in addition, the Germans managed to ford the river east of the bridge. The British withdrew, and the strategic facility was again in the hands of their opponents. Around the same time, units of two Italian battalions from the 213rd Coast Guard Division arrived here.

British 50th Division makes its way to the bridge.

On the night of 13-14 July, the soldiers of the 3rd commando unit captured the Malati Bridge over the Lentini River. The special forces quickly occupied the pillboxes, putting the Italian soldiers guarding the facility to flight. On the morning of July 14, the bridge was attacked by several German battalions, supported by mortars and tanks. According to the British commandos, a "Tiger" (according to another version - Pz.IV) fired at them, which destroyed the bunkers. The commandos planned to hold out until the units of the 50th division arrived, but they got bogged down in battles with the units of Colonel Schmalts near the village of Carlentini. The 3rd unit was forced to retreat south in order to connect with the 50th division (in the battles for the bridge, it lost 30 people killed and 60 prisoners).

On July 14, with the support of artillery and tanks, infantry of the 69th Brigade (commander - Brigadier Edward Cook-Collins) captured the town of Lentini. While the 69th Brigade was fighting, units of the 151st Infantry Brigade (commander - Brigadier Ronald Senior), as well as the Shermans from the 44th Armored Regiment (Squadron "C") made their way to the Malati River and re-captured the bridge (Germans could not destroy it). In the late evening of July 14, the aforementioned units approached the Primosole Bridge - by this time it was already in the hands of the Germans.

Tankmen of the 44th Armored Regiment

Tankmen of the 44th Armored Regiment

Source - desertrats.org.uk

British tankers refused to attack the bridge without artillery support, and even at night. Meanwhile, reinforcements arrived at the Germans - several companies of the 1st Sapper Battalion, the 1st Battalion of the 4th Parachute Regiment and parts of the 1st Artillery Regiment. In addition, Catania had units of the Schmalz group, which had retreated from the south, as well as several Italian battalions and units of the 4th parachute regiment. First of all, the Germans began to equip positions on the northern bank of the Simeto River. On the night of July 14-15, a battle between British gunners and seven Italian armored vehicles broke out near the bridge - the crew of a six-pound cannon under the command of Corporal Stanley Rose burned two of them.

On the morning of July 15, the infantry of the 9th battalion of the Durham regiment tried to attack the north bank on both sides of the bridge (the bridge itself was well-shot, besides, the British thought that it was mined). The Germans repulsed this assault. At a meeting of officers of the 151st brigade, it was decided that the assault should be carried out at night to the left of the bridge upstream of the river, where the depth did not exceed 1.2 m (the ford was indicated by Lieutenant Colonel Pearson). The night assault was preceded by an hour-long artillery preparation.

On July 16 at 2:00 am, two companies of the 8th Battalion ("A" and "D") crossed the ford and announced the occupation of the bridgehead by firing a signal flare. After that, companies "B" and "C" of the same battalion, with the support of tanks from the 44th regiment, moved across the bridge and made their way to the northern bank of Simeto. The Germans opened a hurricane of fire from two 88-mm guns, knocked out four Shermans (the total number of British tanks in the area of \u200b\u200bthe bridge did not exceed twenty units). The British created a bridgehead about 300 m deep, but could not advance further north, since the enemy was entrenched in vineyards and an olive grove.

The bridge is in British hands again

On July 16, the fighting continued with varying success. Private Reginald Goodwin (machine gunner from the 8th battalion of the 151st brigade) participated in repelling one of the German attacks: “With my Bren I managed to destroy two snipers and several enemy soldiers. The secret of success is a comfortable position, as well as the fact that my comrades were covering me from the flanks "... On the same day, units of the 1st parachute brigade were withdrawn to the rear - during the landing and in the battles for the bridge, they lost over 370 people.

An anti-tank gun crew of the 1st Parachute Division is fighting at the Primosole Bridge. July 1943

An anti-tank gun crew of the 1st Parachute Division is fighting at the Primosole Bridge. July 1943

Source - barriebarnes.com

On July 17, at 1:00, units of the 6th and 9th battalions crossed Simeto ford (the bridge was shot through by the Germans) and replenished the forces of the defenders of the bridgehead, taking up positions in the vineyards. At 5:00, the British began to expand the bridgehead. The tanks of Squadrons A and C of the 44th Regiment crossed the bridge and took up positions to the left and right of its northern end. The crews of the Shermans of the 3rd Yeomen Regiment proved to be excellent. At 9:00, the tanks, moving north along the road, destroyed the crew of the 88-mm gun, the truck and suppressed several machine-gun points. At 9:30 am, the regiment's tankmen, supported by infantry from the 151st Brigade, continued their offensive and destroyed two 105-mm guns. According to the reports of the 3rd regiment, on July 17, its soldiers killed 70 German soldiers and officers, and captured four. On that day, the commander of the 44th regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Willis, was killed - a sniper bullet hit him in the head. Major Grant assumed command of the regiment.

In the first half of the day, the Germans actively counterattacked, suffering considerable losses. Hauptmann Heinz-Paul Adolf from the engineer battalion tried to blow up the bridge with a truck loaded with explosives. Adolf died, and his plan did not work - the cars were destroyed before the approach to the bridge. The Hauptmann was posthumously awarded the Knight's Cross. The situation changed after 11:15 am, when the tanks of the 44th regiment took advantageous positions for shelling and opened hurricane fire on German positions. Under the cover of this fire, the British infantry approached the enemy's trenches and began to throw grenades at them. Some of the Germans surrendered, many died, and the rest retreated to the north and took up defenses along with the paratroopers of the 4th regiment. Now the British completely controlled the bridge and its surroundings and began to push the enemy towards Catania.

The scheme of battles for the Primosole Bridge on July 13-17, 1943. Blue arrows indicate the advancement of British units, red - German ones. Yellow circles with numbers indicate the chronology of the battles: 1st and 3rd battalions of the British take control of the bridge; 2nd - 2nd Battalion captures the southern sector near the bridge; 3 - the Germans conduct reconnaissance in force; 4 - the first massive attack of the Shtangenberg and Fassl groups; 5 - repeated attack of the Germans, the British retreat to the southern end of the bridge; 6 - the Germans are crossing the river east of the bridge, the 1st and 3rd battalions are retreating to the positions of the 2nd battalion; 7 - the arrival of units of the 50th division and the 4th armored brigade; 8 - counterattack by the 9th battalion of the Durham regiment and the 44th armored regiment; 9 - the British ford the river and capture the bridge

The scheme of battles for the Primosole Bridge on July 13-17, 1943. Blue arrows indicate the advancement of British units, red - German ones. Yellow circles with numbers indicate the chronology of the battles: 1st and 3rd battalions of the British take control of the bridge; 2nd - 2nd Battalion captures the southern sector near the bridge; 3 - the Germans conduct reconnaissance in force; 4 - the first massive attack of the Shtangenberg and Fassl groups; 5 - repeated attack of the Germans, the British retreat to the southern end of the bridge; 6 - the Germans are crossing the river east of the bridge, the 1st and 3rd battalions are retreating to the positions of the 2nd battalion; 7 - the arrival of units of the 50th division and the 4th armored brigade; 8 - counterattack by the 9th battalion of the Durham regiment and the 44th armored regiment; 9 - the British ford the river and capture the bridge

Source - Greentree D. British Paratrooper vs Fallschirmjäger: Mediterranean 1942-1943. - London: Osprey, 2013

Outcome

In the battles for the Primosole bridge, the 151st brigade lost about 500 people in killed and wounded. In addition, the German paratroopers claimed that they were able to disable 5-7 enemy tanks. The losses of the German side were estimated by the British at 300 people killed and more than 150 prisoners (the Germans recognized the loss of 240 people killed and wounded). It is surprising that during the fighting, the field hospital of British paratroopers did not stop working, which performed several hundred operations. Even when the hospital was captured by the Italians, it did not stop working - the medical staff operated on both the wounded British paratroopers and their enemies.

The fight for the Primosole bridge did not have a serious impact on the course of the battles for Sicily - the allies were never able to encircle the enemy group, which managed to cross the Strait of Messina to the continent. In the battles for the bridge, both sides made serious mistakes. The British made an unsuccessful landing, as a result of which the paratroopers of the 1st brigade lost their ammunition and communications. The Germans did not manage to blow up the bridge.

Sources and Literature:

- Hastings M. The Second World War: Hell on Earth. - Moscow: Alpina non-fiction, 2015

- Blackwell I. Battle for Sicily: Stepping Stone to Victory. - Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2008

- Delaforce P. Monty's Marauders: The 4th and 8th Armored Brigades in the Second World War. - Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2008

- D'Este C. Bitter Victory: The Battle for Sicily, 1943. - New York: Harper Perennial, 2008

- Greentree D. British Paratrooper vs Fallschirmjäger: Mediterranean 1942-1943. - London: Osprey, 2013

- Mrazek J. Airborne Combat: Axis and Allied Glider Operations in World War II. - Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2011

- Sicily: report on the Primosole Bridge operation 1943 July 14–21, by Major F. Jones. - Kew, Richmond: The National Archives, 1943

- Simmons M. Battles for the Bridges // WWII Quarterly 2013-Spring (Vol.4 No.3)

- War Diaries For 3rd County of London Yeomanry (3rd Sharpshooters) 1943

- https://paradata.org.uk

By the early 1930s, the British armed forces, after the First World War, had died on their laurels, had turned into a real reserve of outdated forms of warfare and any innovations in this area were treated condescendingly, if not even hostile. The articles and speeches of the American General Mitchell, who back in 1918 advocated the early creation of large airborne forces, found even fewer fans in England than in the United States. According to British military theorists, there was no longer a worthy enemy in Europe, the "war to end all wars" ended in complete victory for the Entente, and any desire to increase the military power of Germany or the USSR was supposed to be stifled in the bud by increased economic pressure. In these conditions, there was no need to change the time-honored structure of the armed forces, and even more so to introduce such extravagant ideas as the landing of soldiers from the air.

The British felt the need for the use of landing troops only during the conflict in Iraq. After World War I, the British Empire was given a mandate to govern this territory, which was formerly part of Turkey. Iraq has actually become an English semi-colony. Since 1920, lively hostilities began in the country between the troops of the "mistress of the seas" and the local national liberation movement. To compensate for the lack of mobility of their ground forces in the fight against mounted rebel troops, the British transferred a significant number of combat aircraft to Iraq from Egypt, including two military transport squadrons equipped with Vickers "Victoria" vehicles. Under the leadership of Air Vice Marshal John Salmond, a special tactic was developed for the Air Force's actions with their participation in actions to "pacify" the rebel territories. Since October 1922, Air Force units took an active part in suppressing the uprising.

In addition to bombing populated areas and attacking detected partisan detachments, the most important function of aviation was the landing of tactical airborne assault forces in the areas where rebel formations were located with the aim of their swift destruction or capture. The first such action was successfully carried out in February 1923, when 480 soldiers of the 14th Sikh regiment were landed in the vicinity of the city of Kirkuk. The new tactics turned out to be very effective - if earlier the mobile detachments of the rebels, who enjoyed the full support of the population, quickly left the threatened areas, then from that time they were increasingly effectively blocked.

The British significantly developed their tactics: the commander of the 45th military transport squadron Arthur Harris (who later became the head of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command) and his deputy Robert Saundby proposed to create dual-purpose aircraft: transport bombers: In other words, large multi-engine the planes were supposed to both carry out the transportation of troops and land landing forces, and, if necessary, carry out air raids on enemy settlements. From the point of view of colonial conflicts and the lack of air defense among the rebels, the expediency of such a doctrine was obvious, therefore, in the 20s and early 30s, the British built quite a lot of such universal machines (followed by the French and Italians, preoccupied with similar problems - keeping their colonial empires in North Africa). Subsequently, the aircraft Handley Page "Hinaidi" and Vickers "Virginia" in the role of "steel birds of the white man" took part in operations to "pacify" the population of Iraq, British Somalia, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Protectorate of Aden, Yemen and in the battles in the northeastern border of India against Afghans. Thus, the British can be considered the de facto founders of air-ground operations. But the British reacted with a noticeable coolness to the appearance in the early 30s of a new type of troops - airborne troops. So, during the well-known Kiev exercises of the Red Army in 1935, a spectacular massive drop of parachute troops made an impression on anyone, but not on the British delegation. Its head, the old colonial campaigner Major General Archibald Wavell, who later became Field Marshal and brutally beaten by Rommelem in North Africa, sent a critical report on the use of the Airborne Forces to the War Department, pointing out the large dispersal of parachutists after the drop and allegedly associated with this makes it impossible to control the landed parts. Wavell's message, superimposed on the traditional "ossification" of the royal army, permanently delayed the creation of the national airborne forces.

Germany's successful use of its parachute units during fleeting campaigns in Norway and the West in 1940 did not convince the orthodox British military of the need to create similar units of their own. It took almost daily personal involvement of Prime Minister Churchill, who had an obvious weakness for various special units, to get things off the ground. On June 22, 1940, the prime minister issued an order on the beginning of the formation of various special forces, including the Parachute Corps. Unlike the Germans, the priority here belonged to the ground forces, not the air force. Even before the order was issued, in May, at Churchill's personal instructions, the preparation of a separate parachute battalion began. Like the Germans, the British immediately faced serious difficulties related to the novelty of the problem. But if in Germany the development of parachuting was carried out with the full support of the Luftwaffe command and personally Reichsmarshal Goering, then in England the constant sabotage by the Royal Air Force made it extremely difficult to conduct training. There were not enough parachutes and experienced instructors, the material part of the training center (the school was located in the town of Ringway - a southern suburb of Greater Manchester in northwestern England, outside the range of the Luftwaffe) consisted of only 6 old twin-engine Whitley I bombers hastily adapted to jumping (the latter accounted for through the boarding hatch on board, which was extremely difficult for an inexperienced parachutist and threatened with serious injury or death when hitting the aircraft fuselage). Any necessary equipment had to be obtained literally in battle.

It was difficult to find instructors-parachutists - they were led by the famous pilot and athlete-paratrooper, squadron leader Lewis (Lou) Strange (Louis Strange). His closest assistant was another pilot, John Rocc. The tasks of the permanent staff of the school, among other things, included the development of landing techniques for heavily loaded paratroopers, as well as the tactics of group landing - there was no experience in this area in good old England yet.

The first training drop of parachutists was carried out on July 13, 1940; from the volunteers recruited by that time, they quickly formed separate divisions, which gained fame under the general name of the Parachute Regiment ("regiment" in this case is a collective name denoting the type of troops). Paratrooper training took place at both Ringway and the Army Training Center in Aldershot. Despite serious preliminary tests and all kinds of medical commissions, the dropout rate of cadets-paratroopers for various reasons (“refuseniks”, injured and killed) was 15-20 percent, mainly due to the extreme difficulty of jumping from Wheatley aircraft. The very same parachute training of the first British paratroopers was very intensive and good-quality - the first, November 1940, graduation from the school in Ringway (290 people who were entirely enrolled in the 1st parachute battalion and the 11th battalion of the Special Aviation Service) in ten weeks of training completed more than 30 jumps for each student. As mentioned above, many senior officers of the army and especially the air force were categorically against the organization of the airborne troops, so the work to create them fell on a group of young and unorthodox-minded military men, free from the ossified dogmas of British military thought. The deaf wall of rejection from the "military aristocracy", looking at the development of military thought through the monocles of Victorian times, was overcome only in 1941, when he personally visited the Ringway parachute school, watched the jumps and in every possible way kissed the paratroopers, promising them all possible support. This significant event took place in April, and a month later the Cretan operation of German paratroopers broke out, wiping the island's strong British garrison to dust and finally convincing the British of the advisability of creating their own airborne forces.

Military aviation, represented by the General Staff and the Ministry of Aviation, has finally begun to regularly supply the paratroopers with the necessary amount of equipment. At the headquarters of the Air Force, the post of an officer in charge of the affairs of the Airborne Forces, who was responsible for the preparation and coordination of their actions, was introduced; this organizational structure was preserved until the end of the war. In April, a special meeting was held at which for the first time (!) Samples of captured weapons and equipment of German paratroopers were demonstrated to the officers of the airborne forces, and all available intelligence data on the tactics of enemy actions based on the Norwegian and Dutch-Belgian campaigns were transferred. From that time on, the old quarrels between the "traditional" and "innovative" parts of the army were gradually forgotten. Fulfilling Churchill's directive (announced immediately after the Cretan operation), the headquarters of the Royal Air Force began feverish activities to form by May 1942 a five-thousandth parachute brigade, which received serial number 1 - it was based on the already existing 11th battalion of the Special Aviation Service. The same number of paratroopers should have been at the final stage of training (to staff another, 6th brigade). In the future, both brigades were transformed into airborne divisions. The parachutists were commanded by one of Churchill's nominees, Major General Frederick Browning, a former Grenadier Guardsman belonging to high British society. Soon the 2nd and 3rd battalions joined the existing Parachute Regiment - 1st Battalion. Thus, in November 1941, the backbone of the 1st Brigade was formed, which was located in Wiltshire and began active combat training. At this time, the most famous British paratrooper - Major John Frost, who then distinguished himself especially at Bruneville, in Tunisia and Arnhem, got into the ranks of the Airborne Forces. Bombers "Whitley" have finally been removed from service with training units of the Airborne Forces; now training jumps were carried out from tethered balloons. The result was not long in coming: while training more than 1700 people for the 2nd and 3rd battalions in November 1941, there were only two "refuseniks", and a dozen more cadets were injured (for comparison, when jumping from the cramped Whitley landing hatch a year ago, out of 340 people, two died, 20 were injured, and 30 refused to perform the jump).

The paratroopers soon became the pride of the armed forces (even on the famous English poster of the Second World War, "The attack begins from the factory", calling for shock labor in the rear in the name of victory, paratroopers are shown jumping out of a glider). In everyday life they were called "paras" (from the abbreviated word Paratroopers - paratroopers) or, in opposition to the Germans, "Red Devils" - "red devils" (for chestnut berets).

The core of the British Airborne Forces was the 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions (Airborne Division; Airborne Division), the formation of which was completed by 1943. At the end of the war, the 5th Airborne Division joined them, but it did not have time to take a significant part in the hostilities. The 6th division, which became a standard one, numbered about 12 thousand people. It consisted of two parachute brigades (Parachute Brigade) - 3rd and 5th, as well as one landing (Air-landing Brigade) - 6th. Each brigade consisted of three battalions. Reconnaissance regiment (6th Airborne Reconnaissance Regiment) of the division received light tanks "Tetrarch".

In 1944, the airborne division was armed with 16 light tanks, 24 75-mm, 68 6- (57-mm) and 17-pounder (77-mm) anti-tank guns, 23 20-mm anti-aircraft guns, 535 light infantry guns , 392 PIAT anti-tank hand grenade launchers, 46 easel (Vickers Mk I) and 966 light (BREN Mk I) machine guns, 6504 STEN submachine gun and 10113 rifles and pistols. The relative mobility of the division's units was provided by 1,692 units of vehicles (including 904 3/4 ton jeeps, as well as 567 trucks and tractors) and 4502 motorcycles, mopeds and bicycles.

In addition to the actual British units, the Airborne Forces replenished the 1st Canadian Parachute Battaillon. The battalion was formed on July 1, 1942, and in August 85 officers, sergeants and soldiers from its composition arrived in Ringway for special training. The remaining part of the personnel at the end of the year was transferred to Fort Benning, where for four months she studied parachuting together with the Americans. Soon a Canadian parachute training center was established in Shiloh. In the meantime, the battalion, which had completed its training, became part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade of the 6th Airborne Division and took part in Operation Overlord and subsequent battles in Europe (including in the Ardennes on Christmas Day 1944). In March 1945, the Canadians participated in Operation Varsity (landing across the Rhine), and then the battalion was withdrawn to its homeland and disbanded in September.

Following the first battalion, the Canadians manned three more. To this was later added one Australian and one South African battalion, which allowed the British, together with the staff of the 44th Indian Airborne Division (see below), to bring the total number of the Airborne Forces to 80,000 people.

* * *

The first successful military operation of the British paratroopers, however, took place on the coast of the English Channel and was more of a sabotage than a classic combat character. The company of the 2nd Parachute Battalion under the command of Major John Frost on the last night of the winter of 1942 landed from high-speed landing barges on the French coast, attacked a German radar post in the town of Bruneville, eliminated the guards in a short fight and stole secret radar equipment (everything that the paratroopers did not were able to take it with them, was photographed, and then rendered unusable). Having completed the task, Frost's group went ashore without a fight and crossed to the waiting ships, losing only two people prisoners - the latter (radio operators) were unable to find the way to the gathering place in the dark.

The English "couple" received their real baptism of fire during the landing in North Africa - Operation Torch (Torch). Strictly speaking, this action was the first large-scale Allied amphibious operation in World War II, a kind of rehearsal for a future invasion of Europe.

British paratroopers totaling about 1,200 were tasked with capturing a number of important airfields, headquarters and communications centers. In addition, parachute troops landed far on the left flank of the invasion forces were to capture several key points on the road to Tunisia, where the battered German-Italian troops were grouping. The British Airborne Forces in the operation were represented by the 1st, 2nd and 3rd parachute battalions of the 6th brigade, which on the whole successfully coped with their tasks.

The first large-scale action of the newly minted 1st British Airborne Division took place during the invasion of Sicily. To carry it out, the Allies had more than 1,000 transport aircraft and cargo gliders, mainly for the transfer of airborne units (8,830 people) that took part in the landing. During the invasion of southern Italy, in order to secure the deployment of allied forces on the Messinian bridgehead from the side of the "heel" of the Apennine Peninsula, the 1st Airborne Division was landed from a specially assigned detachment of ships and vessels. This was done by special agreement with the command of the Italian Navy, which recognized the terms of the armistice and allowed the paratroopers to land. The convoy left Bizerte (Tunisia) and reached Taranto on 9 September; Only small reconnaissance units were thrown out with parachutes, the bulk of the division's forces, without encountering resistance, entered the Italian coast as an amphibious assault.

The British Airborne Forces in Greece ended their careers in the Mediterranean, when their individual units (including the SAS units) supported the capture of many small islands in the Aegean Sea. On October 2, 1944, following the example of the Germans, the landing on Crete was carried out. Soon, parachute troops landed in mainland Greece. This was due to the powerful pro-communist partisan movement ELAS that developed in the country and Churchill's desire to keep the Balkans in line with traditional British politics. Therefore, the liberation (or occupation) of Greece was planned and carried out as soon as possible in order to prevent the Soviet or Yugoslav troops there. On November 1, an airborne assault force occupied Thessaloniki, and 12 days later the British entered Athens.

In preparation for the landing in Normandy, the 1st and 6th divisions were reduced to the 1st British Airborne Corps (VDK), which, together with the 18th Airborne Corps of the US Army, formed the First Allied Airborne Army (First Allied Airborne Army; VDA) under the command of the American Lieutenant General Lewis G. Brirton. Special transport airborne units were also created: the 2nd Tactical Air Force, allocated by the Royal Air Force for warfare in Europe, included two special-purpose air groups - the 38th Airborne (in Operationally, it was subordinate to the command of the 1st Airborne Army) and 46th Military Transport. They were mainly armed with Dakota vehicles, and there were glider units with towing aircraft.

Shortly before midnight on June 6, 1944, 8,000 people from the 6th Division were dropped on the French coast, northeast of the ancient Norman city of Caen, in order to capture and protect the bridges over the Canal Canal and the Orne River near the town of Ranville from an explosion. The actions of the paratroopers, according to the plan of the developers of the invasion, were supposed to significantly disorganize the German antiamphibious defense and facilitate the landing of the 3rd British Infantry Division of the 1st Corps of the 2nd Army, allocated to capture the "Sword" bridgehead - the left-flank landing area.