Slavs, Varangians and Khazars in the south of Russia. On the problem of the formation of the territory of the ancient Russian state. Old Russian settlements of the Middle Dnieper region: (Archaeological map) Old Russian settlements of the middle Dnieper region

Vivid signs of a settled population appeared in the basin of the Seversky Donets, Oskol and Don only at the turn of the 7th-8th centuries. The interval between these periods is the end of the 4th-7th centuries. (the time of the Great Migration of Nations and immediately after it) - the darkest in archaeological terms in the history of Southeast Europe, which was a kind of "ethnic cauldron". It is practically impossible to determine the ethnicity of rare settlements and burials: the origins of some objects are found in the Baltic States, others in the cities of the Black Sea region, and still others in the Sarmatian-Alanian environment. In any case, the catacomb burials characteristic of the forest-steppe variant of the Saltov culture, which could be dated with certainty to the 5th century, are unknown in this area.

And the climatic conditions of this region, in particular the Dnieper region, at the end of the 4th - beginning of the 6th century. were of little use for life. At the end of the IV century. a sharp cold snap began (it was coldest in the 5th century), it became damp and swampy. Therefore, there is no need to wait for large finds of this time.

But in this case, stationary craft settlements can also serve as an ethnomarking feature. A direct genetic link can be traced between the Saltovsk polished ceramics and pottery of the 6th-7th centuries. the so-called "pastoral" and "kantserovsky" types. Settled

the potters' ki in the Middle and Lower Dnieper regions - Pastorskoe settlement, Balka Kantserka, Stetsovka, chronologically and geographically fit within the boundaries of the Slavic Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture, were indisputably of a different ethnicity.

The Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture belongs to the area of \u200b\u200bdistribution of the Slavic Prague ceramics. This dish got its name from the places of the first finds - in the Czech Republic and in the Zhytomyr region (Korchak settlement). The Slavs made dishes only for domestic and ritual needs. Pottery usually did not go outside the village, let alone sell it to other regions. The Slavs did not know the potter's wheel, and if circular pots and jugs appeared in some Slavic culture, this meant the arrival of some other ethnic group. After the collapse of the alliance of the Slavs with this people, the art of the potter's wheel was forgotten as unnecessary.

And the main type of Prague-Korczak ceramics is molded tall pots with a truncated-conical body, a slightly narrowed neck and a short rim. Most of the dishes have no ornamentation. Only occasionally do we see pots with oblique notches along the top edge of the rim [§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§ Section §§§§§§]. This pottery is typical for all Slavs in the period after the Great Migration and before the formation of the Slavic states. Although later, when pottery workshops were in full swing in the cities, traditional pots continued to be sculpted in the villages. Such was the pottery of the Baltic Slavs, the Danube, the Adriatic and the Dnieper.

Penkovskaya culture extended in the 5th-7th centuries. from the Lower Danube to the Seversky Donets. But unlike the more Western Slavs, the Penkovians did not know the kurgans (urn and pit cremations prevailed) and the temple rings, by which the groups of Slavs are usually distinguished. It is believed that these features were inherited by the Penkovites from the Slavs of the Chernyakhov culture, who were influenced by two centuries of communication with the Goths, Sarmatians, Dacians, Celts, Alans and other inhabitants of the Northern Black Sea region of the 2nd-4th centuries. AD

L 5

main monuments of Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture

/>

The cultural layer in all Slavic settlements is very insignificant. This means that the period of operation of each settlement was short-lived. Obviously, this is due to the turbulent situation at the time. Slavic tribes in the 5th-7th centuries appeared in the historical arena as warriors who disturbed the borders of Byzantium, and it is known that the inhabitants of the Dnieper region also participated in these campaigns. In addition, the slash-and-burn farming system, which was then practiced by the Slavs, required frequent relocations to new places (after the depletion of the soil).

The development of Slavic settlements, like almost everywhere, is haphazard, there are no fortifications. But not only the Slavs lived in this territory. Finger and anthropomorphic brooches (cloak fasteners) are usually called the indicator of Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture. They were produced, according to a number of scientists, at the Pastoral settlement in the Dnieper region.

The Slavs, as you know, before the adoption of Christianity, the deceased were burned. But such brooches have not been found in authentic burials with cremations. But they are found in burials according to the inhumation rite. Such deceased were buried stretched out on their backs, with their heads to the northwest, with their hands lying along their bodies. Finger brooches are located on the shoulder bones - where the cloak was. It is clear that the burial rite is pagan, but not Slavic. However, near the deceased, as a rule, a molded Slavic pot with posthumous food is found!

In general, cloaks with figured clasps were very popular among the peoples who lived on the border with the Roman Empire and experienced its influence, especially on the Danube. The Danube origins of many pastoral decorations, including brooches, are undeniable. The German scientist I. Werner notes the genetic relationship of the finger brooches of the Dnieper region with the fibulae of the Crimean Goths, Gepids and South Danube Germanic groups on the Byzantine territory, noting that the "Germanic" brooches were paired and belonged to women's clothing [********** ************************************************* ***********************************]. A.G. Kuzmin connects the pit corpses on the Penkovo \u200b\u200bterritory, in the inventory of which there are such brooches,

with the Danube rivals, some of whom, after the defeat of the Huns, went with them to the Dnieper region †††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††Ulti encoura) Use of the †††††††††††]

Further, finger brooches, already in the Dnieper form, spread on the Lower and especially on the Middle Danube, within the framework of the so-called Avar culture (it is associated with the arrival of the Avars and the emergence of the Avar Kaganate), penetrate the Balkans and the Peleponnesian Peninsula, as well as in the Mazurian Lake District and the South Eastern Baltic States [‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡]. At least, in the Middle Danube, these brooches fall together with Penkov's corpses. Their distribution area

Further, finger brooches, already in the Dnieper form, spread on the Lower and especially on the Middle Danube, within the framework of the so-called Avar culture (it is associated with the arrival of the Avars and the emergence of the Avar Kaganate), penetrate the Balkans and the Peleponnesian Peninsula, as well as in the Mazurian Lake District and the South Eastern Baltic States [‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡]. At least, in the Middle Danube, these brooches fall together with Penkov's corpses. Their distribution area

traneniya coincides with the localization of the Rugiland region and numerous toponyms with the root rug, ruz. Now there is a theory about the origin of the name "rus" from the ethnonym "rugi". However, it is now impossible to determine the name of the people who buried the deceased with Slavic vessels and in cloaks with fibulae. Moreover, the written evidence of the habitation of Rugs on the Dnieper in the V-VI centuries. AD not.

But the artisans who created these products had nothing to do with the Goths or Rugs, or the Slavs, or those who left Penkov's corpses. At the Pastoral settlement, in addition to pottery workshops, four yurt-like ground buildings and six semi-dugouts, also of non-Slavic origin, were discovered (hearths in the center instead of traditional Slavic stoves in the corner of the house). All these dwellings have analogies in the residential buildings of the Mayatskiy complex of the Saltov culture [§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§ §§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§ §§§§§§§§]. Such buildings are characteristic and

for other pottery settlements of the Dnieper region of that time (Osipovka, Stetsovka, Lug I, Budishche, etc.). B.C. Flerov considers all yurt-like dwellings of the Middle Dnieper region to belong to the Proto-Bulgarians [*************************************** ************************************************* ******].

But in settlements like Stetsovka, ceramics were found not of the Azov, but of the "Alan" type. The presence of yurt-like dwellings here, and not the classical semi-dugouts of the forest-steppe variant of the Saltov culture, is simply explained: the principle of construction of semi-dugouts was borrowed by the inhabitants of the forest-steppe from the Slavs of the Dnieper region, which is recognized by almost all archaeologists. The disappearance of yurt-like premises among the Saltovites of the forest-steppe is also natural. According to research by B.C. Flerov, such dwellings are a transitional type, characteristic of the period of adaptation to a sedentary life. This is quite natural for a people who spent more than two centuries in the recesses of the Great Migration and used to lead a semi-nomadic lifestyle.

The molded ceramics of these centers, which were not produced for sale, are also very different from the Slavic ones and have a clear genetic link with the Sarmatian pots and ceramics of the steppe complexes of the south, and this form continued to exist in the molded ware of the Saltovskaya forest-steppe. †††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††Ulti encoura) Use of the ††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††Adeadepi. Use of] In Slavic Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements, the share of "pastoral" type ceramics is very small - less than 1 percent. As you can see, the Slavs were not the best sales market for pastoral craftsmen. But among the steppe peoples, mainly the Sarmatian-Alans, ceramics enjoyed success. Analogies of pastoral pottery were found not only at the Saltov settlement, but also in Moldova and Bulgaria (in Pliska).

The name of the bearers of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture has long been known. These are antes, well known to the Byzantines and Goths from the events of the 6th - early 7th century. The largest historians of that time - Procopius of Caesarea, Jordan, Theophylact Simokatta - note that the Antes used the same language,

that the Sklavins (a more western group of Slavs) had the same customs, way of life, beliefs with them. But at the same time, the Byzantines somehow distinguished the Sklavin from the Ant, even among the empire's mercenaries. This means that the ants did have ethnographic features. Obviously, the very name "anty" is not Slavic. Most scientists now make it from the Iranian dialects (ant - "marginal"). Many later names of Slavic tribes from the Dnieper to the Adriatic are also Iranian: Croats, Serbs, Northerners, Tivertsy. With regard to the Croats and Serbs, later borrowings are impossible: in the VII-VIII centuries. these tribal unions were for the most part already on the Balkan Peninsula. Therefore, the search for Iranian elements in the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture, which belonged to the ants, became logical.

The existence within its boundaries of pottery workshops, archaeologically associated with the Sarmatian-Alanian environment, allowed V.V. Sedov talk about the formation of the Ant tribal union on the basis of a certain "assimilated Iranian-speaking population", which remained from the time of the Chernyakhov culture [‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡]. But just the assimilation of this Iranian element is not traced (we can only talk about their peaceful coexistence with the Slavs). Pastoral polished ceramics has a direct connection not with Chernyakhovsk, but with the Azov and Crimean forms of the 2nd-6th centuries. AD Unfortunately, the source base is insufficient for a more complete characterization of the “pastoral culture”.

Genetically related to it is the later "kanzersky type" of polished pottery. It became widespread in Nadporozhye and along the Tyasmin river. Its chronological framework is a topic for a separate discussion. Ukrainian archaeologist A.T. Smilenko, using the archeomagnetic method, dated the Kantseri settlement to the second half of the 6th - the beginning of the 8th century. Section §§§§§§§§§§§]. T.M. Minaeva, by analogy in the North Caucasus, shifted the chronological framework higher:

- the beginning of the IX century. [******************************************* ************************************************* ***]. S.A. Pletnev and K.I. The dyes drew attention to the identity of the pottery workshops of the Kantzerka and the Mayatskiy complex, which allowed them to date the Kantzerka to the end of the VIII century. †††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††††Ulti encoura) Use of the †††††††††††††††††††† ul), thus linking this settlement with the "expansion of the Khazar Khaganate."

Indeed, there is no doubt about the Alanian belonging of the pottery complexes of the "kantser type". But there is also no need to revise the date of these settlements established by the physical method. The lower dating of the forest-steppe complexes of the Saltov culture has always been associated with the theory of the resettlement of Alans from the Caucasus, which is dated to the 8th century. However, as we have already seen, there are no grounds for such dating, and archaeological and linguistic materials cast doubt on the very fact of migration of a large Alanian massif. The data of anthropology and numismatics indicate a significant archaic nature of the Mayatsky and Verkhnesaltovsky burial grounds (cranial type and finds of coins of the 6th - early 7th centuries). The Verkhny Saltov burial ground differs from the rest of the Saltov catacomb burials and the North Caucasus: if everywhere the bodies of women are twisted, then in Verkhny Saltov they are stretched out. This allows archaeologists to draw a conclusion about the preservation of the ancient Sarmatian tradition here, which was obsolete in the North Caucasus. Many burials of the Dmitrov catacomb burial ground are also recognized as archaic: analogies to their inventory do not go beyond the 7th century. These facts gave B.C. Flerov's ability to distinguish a special ethnic group Sarmato-Alans while preserving the ancient Eastern European traditions [‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡ ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡]. Therefore, it seems more acceptable to revise the lower boundary of these particular SMK complexes, especially since the upper layer of both the Pastoral settlement and Balki Kantserka has a clear Saltovo-Mayatsky appearance.

Thus, a comprehensive study of materials from archeology, linguistics and epigraphy, as well as reports from written sources, suggests a direct connection between the core of the Russian Kaganate and the Sarmatian-Alanian tribes of the Northern Black Sea region and Crimea of \u200b\u200bthe first centuries AD, especially with the Roxolans. After the Hunnic invasion, some of them appear in the North Caucasus (the region of the Kislovodsk depression), which is confirmed both by the data of Arab-Persian sources about the Rus in the Caucasus in the 6th-7th centuries, and by authentic archeological materials. Another part of these tribes probably migrated to the Dnieper and Don regions, which is indirectly confirmed by the materials of the "pastoral culture" and settlements of the "kantser type", as well as the earliest cultural layer of the Dmitrievsky, Mayatsky and especially the Verkhnesaltovsky complexes, the population of which was significantly different in its material culture from other carriers of the forest-steppe variant of the QMS.

The participation of the “Rukhsas” in the formation of the nucleus of the Russian Kaganate of the Ciscaucasia also finds confirmation. The Mayatsky burial ground provides rich material for solving this issue. The forms of the catacombs and the features of the immobilization rite (partial destruction of skeletons) are very close to the Klin-Yar complex near Kislovodsk, which dates back to the 2nd-4th and 5th-8th centuries.

This rite, known even among the Scythians, was widespread in forms similar to those of the Saltovo-Mayatsk ones in the Chernyakhov culture: in the II-IV centuries. - in the Middle and Lower Dnieper, in the II-V centuries. - in the Dniester and the Bug region, in the Alanian burial grounds of the Crimea. From the II-III centuries. it is known in the catacombs of the North Caucasus, as well as in the catacomb Kubai-Karabulak culture of the III-IV centuries. in Fergana. He expressed himself in the fact that when positioned in the grave, the deceased was cut through the tendons and tied the legs, and after a while (a year or three) after the funeral, the grave was opened and the bones of the deceased were mixed, the chest was destroyed (so that he could not breathe) and the head was separated from the skeleton. All this was done to protect the living from the appearance of the resurrected dead. Depending on the beliefs of the community, in some burial grounds this was applied to all adults, in others - only to those who were

nor performed magical functions. By the way, such actions after the adoption of Christianity were common among the Slavs in Danube Bulgaria, Ukraine, Belarus and the Carpathians.

The archaic nature of part of the inventory of the Mayatsky burial ground and the craniological type, the closest analogies to which are found in the Roksolan burials of the Northern Black Sea region of the 1st-3rd centuries AD, show that migration from the North Caucasus in the VIII century. cannot be assumed. In Klin-Yar, such burials appear since the 5th century. AD, and the burial ground functions continuously. From V to VIII century there was no outflow of population from these places. Obviously, both Klin-Yar and Mayatsky complex were settled by kindred clans who returned from campaigns during the Great Migration. The same is the connection of other ancient complexes of the Saltov culture with the monuments of the 5th-9th centuries. near Kislovodsk. That is, the core of the Saltovites appeared in the Don region in the 6th century. and immediately established relations with the Slavs. This marked the beginning of the history of the Rus of the Saltov culture.

Ambroz A.K. Nomadic Antiquities of Eastern Europe and Central Asia V-VIII centuries. // Archeology of the USSR. The steppes of Eurasia in the Middle Ages. M., 1981. S. 13-19; Wed: Aybabin A.I. Burial of a Khazar warrior // SA. 1985. No. 3. P. 191–205.

Mongayt A. L. Ryazan land. M., 1961. S. 80–85.

PVL. M .; L., 1950. Part 1.P. 16, 18.

V.O. Klyuchevsky Op. M., 1989.Vol. 1.P. 259. On the close views of Lyubavsky and Hrushevsky on the role of the Khazars, see: Novoseltsev A.P. Formation of the Old Russian state and its first ruler // Vopr. stories. 1991. No. 2/3. S. 5.

From generalizing works, see: E. L. Goryunov The early stages of the history of the Slavs of the Dnieper Left Bank. L., 1981; V. V. Sedov Eastern Slavs in the VI-XIII centuries. M., 1982. S. 133-156; Ethnocultural map of the territory of the Ukrainian SSR in the 1st millennium AD e. Kiev, 1985. S. 76-141; O. V. Sukhobokov Dniprovske lisostepov Livoberezhzha near VIII – XIII centuries. Kiev, 1992; see also: Shcheglova O.A. Saltovskie things on the monuments of the Volyntsev type // Archaeological monuments of the Iron Age of the East European forest-steppe. Voronezh, 1987, pp. 308–310.

A. N. Nasonov "Russian land" and the formation of the territory of the Old Russian state. M., 1951. On inaccuracies in the use of sources in ancient Russia, see: Konstantin Porphyrogenitus. On the management of empires. M., 1989. Comment. S. 308-310.

Novoseltsev A.P. Decree. op.

G. F. Korzukhina Russian treasures. M .; L., 1954, pp. 35–36.

Noonen Th. The first major silver crisis in Russia and the Baltic from 875 - p. 900 // Hikuin... 1985. No. 11. P. 41-50; Wed: V. V. Kropotkin Trade relations of Volga Bulgaria in the X century. according to numismatic data // Ancient Slavs and their neighbors. M., 1970.S. 149.

Petrukhin V. Ya. On the problem of the formation of the "Russian land" in the Middle Dnieper // DG, 1987, M., 1989. P. 26-30.

Blifeld D. I. Old Russian memory "yaki Shestovitsi. Kiev, 1977. S. 128, 138.

Petrukhin V. Ya. Varangians and Khazars in the history of Rus // Ethnographic Review, 1993. No. 3.

Wed: Motsa A.P. Log tombs of southern Russia // Problems of archeology of southern Russia. Kiev, 1990.S. 100; Guryanov V.N., Shishkov E.A. Mounds of Starodubsky opolye // Ibid. Pp. 107–108; V. V. Sedov Decree. op. S. 151-152.

O. V. Sukhobokov Decree. op. S. 17-18, 65; Ethnocultural map ... pp. 110, 117; Petrashenko V.A. Volyntsevskaya culture on the right bank of the Dnieper // Problems of archeology of South Russia. P. 47; Karger M.K. Ancient Kiev. M .; L., 1958.Vol. 1.P. 137.

PSRL. Pg., 1923.Vol. 2, no. 1. Stb. 43–44.

Wed: Archeology of the Ukrainian SSR. Kiev, 1986. T. 3. S. 326–327.

Konstantin Porphyrogenitus. Decree. op. P. 390.

Guryanov V.N., Shishkov E.A. Decree. op. S. 107-111; Shishkov E.A. On the origin of early medieval cities in the Bryansk Podesenye // Tr. V International Congress of Slavic Archeology. M., 1987.Vol. 1, no. 26, pp. 134–138.

Padin V.L. Kvetunsky old Russian burial mound // SA. 1976. No. 4. P. 197–210.

Avdusin D.L., Pushkina T.A. Gnezdovo in the research of the Smolensk expedition // Vesti. Moscow un-that. Ser. 8. History. 1982. No. 1.P. 75.

Shinakov E.A. Decree. cit .; Izyumova S.A. Suprut monetary treasure // History and culture of the ancient Russian city. M., 1989. S. 213. Suprut - Vyatichi center, judging by the finds of treasures and individual things associated with both Khazaria and the North of Europe. Saltov's things were also found at the Gornal settlement.

Aleshkovsky M. Kh. Mounds of Russian warriors of the XI-XII centuries. // CA. 1960. No. 1. S. 83, 85, 89.

Shinakov E.A. Decree. op. 124

Motsa A.P. Some information about the spread of Christianity in the south of Russia according to the funeral rite // Rituals and beliefs of the ancient population of Ukraine. Kiev, 1990.S. 124; Balint Ch. Burials with horses among the Hungarians in the 9th-10th centuries. // Problems of archeology and ancient history of the Ugrians. Moscow, 1972, p. 178, Zavadskaya SV. Possibilities of source study of "Holidays" - "feasts" of Prince Vladimir in the annals of 996 // Eastern Europe in antiquity and the Middle Ages. Abstracts of reports. M., 1990. S. 54–56) do not negate the real ethnocultural origins of the very social terminology.

Melnikova E.A., Petrukhin V. Ya. The name "Rus" in the ethnocultural history of the Old Russian state (IX-X centuries) // Vopr. stories. 1989. No. 8. P. 24–38.

Pashuto V.T. Russian-Scandinavian relations and their place in the history of early medieval Europe // Sk. Sat. Tallinn, 1970. Issue. 15, pp. 53–55.

ABOUT . M . Prikhodnyuk

From the collection “Early Slavic World. Materials and Research ", 1990

The discovery of early medieval monuments is associated with the territory of the Middle Dnieper region, which became standard for a whole group of antiquities common on the borderlands of the Eastern European steppe and forest-steppe. We are talking about materials from settlements near the village. Hemp trees in Potiasminye, which were mined as a result of the work of the Kremenchuk new-building expedition in 1956-1959. 1 The discoverer and their first interpreter, D.T. Berezovets, considered all four sites near S. Penkovka (in the district Molocharnya, Lug I, Lug P and Makarov Island) as links of one evolutionary development of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bgroup of antiquities dated by him to the 7th-9th centuries. AD In his opinion, the early Tyasma sites are characterized by molded non-ornamented ceramics. In later settlements, items close to the utensils of the Luki-Raikovetskaya culture prevailed. According to the observations of D.T.Berezovets in Molocharn, where exclusively molded dishes were found, there were most biconical pots, in ur. Meadow I - smaller, on Luga II - only a few specimens, in the settlement of Makarov Island, biconical pots were generally absent. For pottery ceramics, the opposite process was noted - an increase in its number at later sites 2.

However, materials from settlements near the village. Hemp were compared in total, without taking into account the individual characteristics of dishes from individual building complexes. This led to a contradictory interpretation of the Penkovo \u200b\u200barchaeological complex. Some researchers consider only early monuments with exclusively molded utensils to be Penkovsky, others - both early and later sets with stucco and ceramics formed on a hand circle 4, others consider only late complexes, similar to those found on Luga I and Luga II, Penkovsky. There were even attempts to deny the semi-earthen character of Penkov's house-building in the Middle Dnieper region.

As a result of the study of archaeological materials from the village. According to the objects, it was established that in Molocharna there is one, the earliest layer, and on Makarova Island, the layers of the Sakhnovka and Luki-Raikovetskaya stage are represented. On Luga I and Luga II, there are three construction periods - the stages of Luka-Raikovetskaya, Sakhnovka and Molocharnya. Only the earliest objects, with specific molded ceramics, are included in the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture, since the upper building complexes in the appearance of archaeological materials are close to the monuments of Luka-Raikovetskaya. They do not possess a sufficient number of specific features that would make it possible to classify them as Penkovian antiquities or to single them out as an independent archaeological culture.

To check the results obtained, excavations were undertaken of early medieval monuments of the Middle Dnieper region near the ss. Sakhnovka, Vilkhovchik, Budishche, Guta-Mikhailovskaya, which confirmed the observations made when working on the materials of the group of settlements near the village. Hemp 7. In subsequent years, the Middle Dnieper Slavic-Russian expedition under the leadership of the author continued to study the Penkovo \u200b\u200bantiquities of the region. New excavations were undertaken in settlements in cc. Budische, Kochubeevka, Sushki, Belyaevka, Zavadovka, and route reconnaissance along the river. Rossave and Umanka and along their tributaries. In addition, Penkovo \u200b\u200bobjects were discovered during excavations of monuments of other cultures: by the new-building expedition "Dnepr-Donbass" under the leadership of D.Ya. Telegin near the village of Osipovka in Poorelya, by the Historical and technical expedition led by V.I.Bidzili near the village of Zavadovka in Nizhny Porosie, the Belotserkovskaya expedition led by R.S. Orlova in the city of Belaya Tserkov on the river. Ros. Exploration in Poorelye by the Dnepro-Donbass expedition discovered a number of new Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements. As a result of field work in the Middle Dnieper region, 36 new Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements were discovered (Fig. 1).

New materials confirm earlier observations about the nature of the Penkovo \u200b\u200barchaeological complexes. This concerns the low-lying location, small size and unsystematic planning of settlements, their location in "nests" of 5-7 together, the nature of house-building and ceramic complexes. Study of settlements in wide areas near cc. Kochubeevka and Sushki showed that the Penkovo \u200b\u200bdwellings were located haphazardly at a distance of 15-40 m from each other (Fig. 2). Most of the excavated houses were quadrangular semi-dugouts with an area of \u200b\u200b7.5 - 24 square meters (Fig. 3; 4: 1-6; b: I). Sometimes they have trapezoidal outlines in plan (Fig. 4: 3.5). Only semi-dugout No. 2.4 from Kochubeevka was distinguished by its large size - 34.7 square meters (Fig. 4: 6). Most often, dwelling pits are oriented at angles to the cardinal points with slight deviations in one direction or another. Lola were at a depth of 0.9-1.6 m from the modern surface. The earthen walls of the semi-dugouts are vertical, the corners of the pits are straight or rounded. In semi-dugouts No. 1, 3 from Kochubeevka and No. 2.4 from Sushki, holes were cleared from the wooden vertical supports of frame walls in the corners and in the center of the opposite walls (Fig. 4: 2,3,5). These are traces of vertical supports that supported the ridge girder of the roof.

Among early Penkov dwellings, semi-dugouts with hearths and hearth spots occupy a dominant position. They were found in dwellings nos. 3,4 from Kochubeevka, no. 4 from Sushki, no. 3 from Belyaevka, no. 2 from Zavadovka, no. 3 from Osipovka (Fig. 4: 3,5,6; 3; 5: 1). Only in early Penkovskaya semi-dugout No. 2 from Kochubeevka was a stone furnace cleared (Fig. 4: 4). Small holes dug in the floor closer to the center of the buildings are a specific detail of early Penkov's house-building. They were found in dwellings No. 3 from Kochubeevka and No. 3 from Belyaevka (Fig. 4: 3-5; 3). It is generally accepted that such pits determine the location of the central pillar, which reinforced the ridge run. However, calculations of the thickness of the supporting structures established that such a support was not needed in small semi-dugouts. Most likely, such a hole has nothing to do with the central support of the floor. It is not always located strictly in the center of the building, but is somewhat shifted towards the hearth.

At the later stages of the existence of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture, almost everywhere there was a replacement of hearths in dwellings with a stove-heater. In the second phase of the culture's existence, foci are sometimes preserved in the southern regions of the Middle Dnieper region (dwellings No. 1, 9 from Osipovka). In semi-dugouts No. 2 1-4 from Kochubeevka, and No. 5 from Sushki and No. 2 from Zavadovka, there were household pits of an oval shape, and in dwelling No. 3 from Belyaevka, in the northeastern corner, a utility pit was cleared in the lining, which went beyond the perimeter of the building (fig. 3)

An interesting detail of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bhouse-building is the indentations that protruded beyond the perimeter of the pits. They were found in dwellings no. 2 from Kochubeevka, no. 3 from Belyaevka, and no. 3 from Osipovka (Fig. 3; 4: 4). The entrances were dug up to floor level (Kochubeevka, Osipovka) or had several steps (Belyaevka). In semi-dugout No. 3 from Osipovka, wooden structures from the facing of the entrance have been preserved.

The outbuildings that were investigated in the settlements from Kochubeevka and Sushki had a sub-rectangular shape with rounded corners measuring from 2.4 x 1.6 m to 3.9 x 2 m and a depth of approx. 1 m from the modern surface. Their floor is flat, the earthen walls of the pits are vertical. Apparently, such buildings were used as sheds. All the household pits that were investigated in the settlements from Kochubeevka, Sushkov and Belyaevka were round or oval in plan with a diameter of 0.8 to 1.9 m. Their walls are vertical or slightly narrowed towards a flat bottom. The outbuildings were made of adobe or made of small stones. Of interest are the remains of an adobe forge from Sushki, which was located on the northwestern outskirts of the settlement near the water.

In Kochubeevka, the layout of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bhousehold was traced, consisting of dwelling No. 2, four utility pits (No. 1-4), outbuilding No. I and two outbuildings (No. 1,2), somewhat remote from the buildings. Apparently, this group of buildings was part of the yard of an individual household (Fig. 2).

At the Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements of the Middle Dnieper region, houses of nomadic appearance were studied. This is an oval yurt-shaped dwelling from Osipovka, sunk into the ground, and a large sub-rectangular semi-dugout from Budishch (Fig. 4: 1; 6: 1). A peculiar feature of the yurt from Osipovka is the foundation dug in the ground, which is almost never found among real nomads. "In essence," writes S. A. Pletneva, "semi-dugout yurts, round in plan, are already the dwellers of the sedentary population, who have mastered the basic principles of construction of permanent dwellings. , the location of the hearth in the center of the floor "9. According to V.D.Beletsky, who was engaged in the classification of Saltov dwellings from Sarkel, the semi-dugout from Budishchi belongs to pillarless. ten

The filling of these buildings was dominated by stucco Penkovo \u200b\u200bcrockery (Fig. 6: 2-10,13,14; 7: 1-4,6-17). In addition, in a yurt from Osipovka, internal handles from clay cauldrons were found (Fig. 6: II, 12), and in a semi-dugout from Budishch there was a breakup of a pottery jug of a kantser type (Fig. 7: 5). A characteristic feature of the molded ceramic set of buildings of a nomadic appearance was organic impurities in the clay dough and the presence of rough notches along the rim edge (Fig. 6: 3; 7: 1-4.9). These features were very characteristic of the nomadic pottery production of the 1st millennium AD.

The presence of houses of a nomadic appearance on the Penkovo \u200b\u200bmonuments of the Middle Dnieper region is evidence of the existence of a territorial community in the society of the Penkovo \u200b\u200btribes of this region. The penetration of the steppe population into the agricultural Slavic environment is completely excluded under the dominance of clan relations and is possible only if there is a territorial community, which could include elements of different ethnicities. Being involved in a single economic process, these elements quickly lost their culture, dissolving in a more numerous ethnic massif.

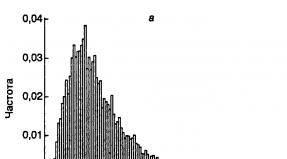

During excavations of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bmonuments, stucco ceramics with a smooth or bumpy surface are most often found. In the north of the Middle Dnieper region, grit and sand predominate in the clay dough of Penkovo \u200b\u200bceramics, and in the south - chamotte and organic impurities. The material obtained during excavations in Budishchi, Kochubeevka, Sushki, Belyaevka and other places makes it possible to create a fairly complete typology of stucco Penkovo \u200b\u200bware. In its development, the principles developed by I.P. Rusanova for the Prague ceramic set. Their essence lies in the determination of the proportions and profiling of the vessels according to four parameters: the ratio of the height of the vessels and the height of their greatest expansion, as well as the ratio of the diameter of the greatest expansion and the diameter of the throat 1. When working with Penkov sets, profiling of products becomes important, in particular the presence or absence of a rib on the body.

Based on these features, all Penkovo \u200b\u200bceramics from the territory of the Middle Dnieper region can be divided into 8 types.

The first type includes biconical dishes with a sharp or rounded fracture in the middle or upper third of the body (30-38%). The rounded corolla of the vessels is not marked or bent outward. There is a stuck-on roller under the rim (Fig. 5: 2,5; 8: 2,5,7,12; 9: 4,8,10; 10: 3; 11: 1,5,8,9,16; 12: 1,4,10,12). The second type of ceramics is made up of squat pots with a rounded body, having a maximum expansion in the middle of the height (26-43%), They have a short rim more or less bent outward (Fig. 8: 8, 11,13; 11: 3,4,11 , 14,15; 12: 2,3).

The third type is made up of pots of slender proportions with a rounded, maximally widened body in the middle of height (9-13%). Their rim is slightly bent outward (Fig. 8: 4.9; 9:11; 11:10). Pots of slender proportions with maximum expansion in the upper third of the height, which have well-defined shoulders and a rim that is vertical or bent outward, are classified as type 4 (4-10%) (Fig. 8: 1; 9: 1; 12: 5). The fifth type includes tulip-shaped vessels with an open neck without shoulders and neck, with a rim slightly bent outward, and sometimes with an extended ridge in the middle of the height (3-6%) (Fig. 10: I). The sixth type of pottery is represented by pots of various proportions with a narrowed bottom and widened upper part (3-5%). Their unselected edge is bent inward (Fig. 5: 3; 9: 6; 12: 6). The complex of the Penkovsky set includes bowls of various shapes, constituting the seventh type of ceramics (4-8%) (Fig. 8: 3; 9: 5; 10: 2.4). The eighth type is small circular vessels with almost vertical or slightly rounded walls (3-4%). Their corolla is barely outlined or not marked (Fig. 5: 4; 9: 7, 12; 12: 7). Flat discs and pans are very characteristic of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture (Fig. 8:14; 9: 14-16; 10: 5; II: 2.12, 12: 8,9,13; 14-16). Discs are available without rim and with a small rim. For frying pans, the rim 1-1.5 cm high is vertical or slightly bent outward.

Early Penkovo \u200b\u200bsets include pottery ceramics of Chernya-Khov's appearance (Fig. 8: 6,10; 9: 9), and later ones - pastoral, officeware (Fig. 7: 5). Sometimes one comes across fragments of amphorae with dense corrugations along the body.

Penkovo \u200b\u200bmolded utensils can be divided into three quantitatively unequal groups. The first includes the most numerous forms of ceramics that make up the traditional household core of a ceramic complex (types 1-3). The second includes forms borrowed from contacting synchronous cultural arrays (types 4-5). The third includes a few ceramic forms taken from the previous Chernyakhov culture (types 6-8).

Among other ceramic finds in the Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements of the Middle Dnieper region, biconical or rounded spindle whorls should be noted (Fig. 13: 10-14, 18-24). A ceramic crucible with traces of bronze on the inner surface comes from Budishchi. Stone products are represented by whetstones (Fig. 13: 16,17). From the bone were made "polished" and punctures (Fig. 13: 8). At the settlement of Osipovka a fragment of a figured bone loop from a quiver was found (Fig. 13: 3). Glassy paste beads were found in Sushki and Osipovka (Fig. 14: 3.8). A few finds are handicrafts made of non-ferrous metals. This is a fragment of a zooanthropomorphic brooch from Dezhek, a bracelet with widened ends from Novoseliya, a ring with curled ends and a bronze plate with riveted details (possibly a fragment of a cauldron) from Sushki (Fig. 14: 1,2,6). Products made of ferrous metals are represented by small knives with a straight back and a flat handle (Fig. 13: 5-7), a fragment of a sickle with a hook and a rivet for attaching to a wooden handle from Kochubeevka (Fig. 13: 2), a chisel from Sushkov ( fig. 13: 9), a chisel from Budishche (fig. 13: 4).

The metallographic study of forge products was carried out by G.A. Voznesenskaya. Samples of items from Kochubeevka, Sushki and Budishch were taken for analysis. Studies have shown that the use of certain technological methods is not associated with any category of products. Forging different in nature have the same scheme, and different materials and manufacturing methods can have the same typological forms. In general, the Penkovo \u200b\u200bforging forgings are distinguished by the simplicity of their technological characteristics. Almost all items are forged from blast iron or heterogeneous raw, mostly mild steel. A sickle from Kochubeevka had a packet structure.

Of the technological methods that improve the working qualities of tools, heat treatment is encountered. Sometimes you come across things in the manufacture of which iron-steel welding and carburizing are used.

Important data were obtained in the study of osteological material. Judging by the animal bones identified by O.I. Zhuravlev, the main part of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bherd was made up of cattle, the second place belongs to pigs, then go small cattle and a horse (Table 1). This composition of domestic animals is typical of a sedentary agricultural economy. The bones of wild animals and fish are much less common, which indicates the secondary role of hunting and fishing in the economy of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture tribes. Among the bones of wild animals, the remains of a red deer and a wild boar are more common, then a roe deer and a hare.

Table I

The data on the crops grown by the Penkov culture tribes were obtained by paleobotanical studies of cereal grain imprints on ceramics. On dishes from the settlements of Kochubeevka and Osipovka, GA Pashkevich found prints of four types of wheat (dwarf, dwarf-soft, two-grain, soft), millet, two types of barley (scarious and bare-grain), oats, rye. Finds among cereal crops of various cyclic plants suggest the presence of crop rotation. Apparently, sowing of winter and spring crops alternated.

The identification of the early stage of its existence is one of the most important achievements in the study of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture of the Middle Dnieper region in recent years. In the previous time, the most widespread were the late materials, which were characterized by semi-dugouts with stoves, a relatively homogeneous ceramic material represented by coarse biconical and rounded pots, frying pans, and, in a lesser extent, dishes of the Prague and Kolochin look. Such a complex was accompanied by fragments of pastoral and stationary pottery ceramics, finger, zoomorphic, zooanthropomorphic fibulae and items of Martynov type belt sets. In general, the second phase of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture dates back to the 6th-7th centuries. AD 12

Among the II best preserved semi-dugouts from excavations of recent years, 8 belong to the early stage of the existence of culture. All of them are characterized by semi-dugouts of sub-square outlines with hearths or hearth spots, pits located closer to the center of the buildings, and some specificity of ceramic sets. Early Peninsula biconical pots most often have slender proportions and a clear rib on the body. A sign of archaism is the presence of items with a smoothed and sometimes underdeveloped surface among the molded dishes, the presence of sticky knobs and crescents on the top of the pots, and the presence of discs. Early borrowings from the Chernyakhov antiquities include molded pots with a curved edge and fragments of gray pottery of the Chernyakhov appearance. The correlation of the signs of the first and second phases of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture are shown in carrelation table II. When compiling it, some materials from previous excavations were used.

Table II

In determining the chronology of early Penkovian antiquities, an important place belongs to the stratigraphy of settlements from Belyaevka and Zavadovka, where there were cases of cutting of Chernyakhov's dwellings by early Penkovsky semi-dugouts.

These facts testify to the existence of objects of the first phase of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture in the postlechernya-Khovsk time, up to the appearance of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bantiquities of the developed stage. The necessary materials are also available for their absolute dating. By the end of the 5th century AD. the ring with curled ends from Sushki belongs. 13 According to European analogies U century AD a massive silver buckle from burial no. 4 at the third burial ground from Bolshaya Andrusovka dates from. A number of other things are happening from other territories that date the first phase of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture to the middle of the 1st millennium AD. By the 4th-5th centuries A.D. a large iron crossbow fibula from an early Penkovs dwelling in the settlement of Kunya in the Southern Bug belongs. By analogy from Chmi-Brighettio to the 5th century AD. a bronze mirror with a solar sign and traces of an ear on the back, found at the Penkovsky settlement of Khanka II in Moldavia 16. Based on the above facts, the first phase of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture can be dated between the first half of the 5th - the turn of the 5th-6th centuries A.D.

In the early phase of the existence of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture of the Middle Dnieper region, there were outlined ways of infiltration into the local cultural environment of elements of adjacent archaeological massifs. Thus, the appearance of stone stoves in Penkovo \u200b\u200bsemi-dugouts can be associated with influences from the Prague-type culture, for which stoves-stoves are a traditional detail in household construction. This also explains the presence of Prague-style pots (type IV) among Penkov's ceramic sets. Under the influence of Kolochin antiquities, tulip-shaped pots (type V) appear in the Middle Dnieper region. The influence of the steppe dwellers on the population of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture of the southern regions of the Middle Dnieper is very noticeable, which is manifested in the presence of houses of nomadic appearance on the Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements, ceramics with organic impurities in clay dough and pots decorated with rough notches along the edge of the rim.

New Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements in the Middle Dnieper region

1, 2. Babichi village, Kanevsky district, Cherkasy region. On the first elevated floodplain of the right bank of the river. In 1979, a large amount of stucco Scythian and Penkovsky ceramics was collected on the area of \u200b\u200b200 x 50 m in Rossava. A biconical spindle and several ancient Russian shards of the XII-XIII centuries were also found there.

On the territory of the northwestern outskirts of the village, on the rise of the first floodplain of the right bank of the Rossava, in an area of \u200b\u200b1000 x 100 m, Scythian ceramics were collected in 1979. In the center of this area, there were stucco shards of Penkov.

3.c. Baybakovka, Tsarychanskiy district, Dnipropetrovsk region To the west of the village, on the left bank of the Orel river, the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin in 1970 collected stucco ceramics from Penkovo.

4. White Church of the Belotserkovsky district of the Kiev region. On Paliyeva Gora, located on the high left bank of the Ros River, there is a fortified settlement with a diameter of approx. 55 m. Exploration excavations of the Belotserkovskaya expedition led by R.S. Orlov in 1978, there were discovered the remains of a semi-dugout 3.7 m wide. In its filling were found molded ceramics and an iron buckle (Fig. 11: 10-15; 13: 5 ).

5. c. Belyaevka, Aleksandrovsky district, Kirovograd region In 1982, stationary archaeological excavations were carried out at the settlement with the Chernyakhovsky and Penkovsky cultural layers, which is located 250 m southeast of the village, at the sources of the Belyaevsky Yar. In addition to the Chernyakhov objects, the remains of two Penkovsky semi-dugouts and one utility pit were investigated there.

Dwelling No. 3 overlapped the Chernyakhovskoye ground dwelling No. 2. It was a semi-square sub-dugout with dimensions 3.4 x 3 m and a depth of 1.3 m from the modern surface. The building is oriented with walls strictly to the cardinal points. The walls of the earthen pit were vertical, the leveling floor was greased with clay and well rammed. Along the southern wall there was a small elevation up to 0.4 m wide and 0.2 m high from the floor level. Near the southeastern corner, a 0.9 m wide entrance was cleared, protruding 0-4 m beyond the perimeter of the depression. The entrance had three mainland steps 0.3–0.35 m wide and 0.2–0.3 m high. The lower step was located inside the dwelling, it was formed by a specially left continental elevation. In the center of the floor of the building, a hole with a diameter of 0.2 m and a depth of 0.2 m from the floor level was cleared.

Two more pits were found in the center of the western and eastern sides, at a distance of 0.3-0.4 m from the walls. The pits are oval in plan, approx. 0.25 m and a depth of 0.1 m from the floor. In the northwestern corner there was an oval pit, which extended 0.4 m beyond the perimeter of the building. Its larger diameter was 1.1 m, and the depth from the floor level was 0.6 m. There was no hearth in the semi-dugout; only near the utility pit there were very faint traces of burning (Fig. 3). Small fragments of molded ceramics (ribbed and rounded pots, fragments of discs), small fragments of Chernyakhov's pottery were found in the dark filling of dwelling No. 23. A fragment of an iron buckle was found in the pit.

Dwelling No. 4 was largely destroyed during excavation work. The length of the semi-earthen is 3.6 m, the width of the remaining part is 0.9-1.1 m. The depth of the building reached 1.1 m from the modern surface. Judging by the surviving part, it had a quadrangular shape. In the lower layers of its filling, rounded and ribbed molded ceramics, fragments of pans were found (Fig. 11: 1-4).

Pit No. 6 was located 3 m north-west of semi-dugout No. 3. It is almost round in plan, with walls slightly narrowed towards the flat bottom. The diameter of the recess is 1.1 m, the depth is 1 m from the modern surface. In the dark filling of the pit there were single fragments of hand-made Penkovo \u200b\u200bdishes.

6. Boguslav city, Boguslavsky district, Kiev region. At the elevation of the left bank of the river. Ros, at the confluence of the Karyachevka brook on an area of \u200b\u200b50 x 50 m. A.P. In 1982, Motsya collected stucco and old Russian ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200band pottery.

7.s. Budische of the Cherkassk district, Cherkassk region In 1979, small archaeological excavations were undertaken at the settlement, where stationary work was carried out in 1978. Semi-dugout No. 3 was cleared, sub-rectangular in plan with rounded corners measuring 6 x 4.2 m and a depth of 0.8-0.9 m from the modern surface ( fig. 4: I). The building is oriented with corners almost to the cardinal points. The walls of its pit were vertical, the well-rammed floor lowered to the center, where there was a stone hearth of oval shape with a diameter of 1.6 m. Large ochdga stones were packed into a specially prepared pit 15-20 cm deep. In the northern, eastern and In the western corners of the dwelling there were round pits with a diameter of 1.3-1.8 m and a depth of 15-20 cm from the floor level. Near the southern corner, a sub-rectangular ledge 1.6 m wide was cleared, extending 0.7 m beyond the perimeter of the walls. Apparently this is the entrance to the dwelling. In the carbonaceous filling of the semi-dugout, a large amount of stucco ceramics was found, the collapse of a narrow-necked pottery jug of the kantor type, the leg of a light clay amphora, fragments of a clay crucible with bronze scum, ceramic spinning wheels, stone donkeys, an iron buckle, an iron chisel, a silver ring (Fig. 7: 1-17 ; 13: 4,10, 13, 23)

8.s. Gamarnya, Kanevsky district, Cherkasy region 0.5 km west of the village, on the rise of the first terrace of the left bank of the river. Rossava, in Selyukovo, on an area of \u200b\u200b300 x 50 m in 1979, stucco ceramics of Penkov was collected.

9.10. from. Gerenzhenovka, Uman district, Cherkasy region In 1979, penkovskaya stucco ceramics were found on the household plots of the western outskirts of the village, on the first floodplain of the left bank of the Umanka River (height 4-5 m) on an area of \u200b\u200b200 x 50 m.

On the first left-bank terrace of the Umanka River, occupied by household plots, near the bridge and at the confluence of a nameless stream into the river, on an area of \u200b\u200b200 x 40 m in 1979, stucco Penkov ceramics were collected.

11.Gorodetskoe village, Umansky district, Cherkasy region. In the southeastern part of the village, on the first terrace of the right bank of the Umanka River, occupied by household plots, in 1979, on an area of \u200b\u200b200 x 40 m, fragments of Penkovo \u200b\u200bceramics were collected.

12.s. Gupalovka, Magdalinovskiy district, Dnipropetrovsk region On the northern side of Lake Perevoloka, the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin in 1970 collected fragments of stucco Penkovo \u200b\u200butensils.

13.14. from. Dakhnovka, Cherkasy district, Cherkasy region In the vicinity of the village, on the low parts of the right bank of the Dnieper River, washed away by the waters of the Kanev Reservoir, the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin in 1980 discovered two localities with stucco ceramics of the Penkovian appearance.

15. c. Dezhki Boguslavsky district, Kiev region. 2-2.5 km southeast of the village, on the right bank of the river. Ros in ur. Chornobaevka in 1960, R.V. Zabashta discovered a settlement with Chernyakhovsky and Penkovsky materials. Among the finds stands out a fragment of a silver zooanthropomorphic brooch (Fig. 13: 1).

16. c. Zavadovka Korsun-Shevchenkovsky district, Cherkasy region During the exploration of the Chernyakhovsky settlement in 1978, a historical and technical expedition led by V.I. Bidzili, the Penkovskaya semi-dugout No. 2 was excavated, which cut through the Chernyakhovskaya semi-dugout No. 1 by the south-western side. The Penkovskaya building

was sub-square in plan with rounded corners measuring 3.7 x 3.5 m and a depth of 1.1 m from the modern surface (Fig. 5: 1). It is oriented with corners to the cardinal points. Almost in the center of the floor there was a round hearth with a diameter of 0.5 m. Another burning 1 m long was traced in the eastern corner. Between the southern wall of the pit and the central hearth, a utility pit was cleared of a circular shape with a diameter of 0.7 m. At the center of the northeastern and southwestern walls of the semi-dugout, two round pits were cleared from pillars with a diameter of 10-20 cm in the filling of this dwelling. hand-made Penkovo \u200b\u200bdishes (Fig. 5: 2-7).

17.c. Kotovka, Magdalinovskiy district, Dnepropetrovsk region On the left bank of the river. In 1970, the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin traced traces of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlement in the form of clusters of molded thick-walled ceramics.

18.p. Kochubeevka, Umansky district, Cherkasy region Rannepenkovskoe settlement near the village. Kochubeevka is located on the eastern outskirts of the village, at ur. Levada. It occupies two elevations of the first floodplain of the right bank of the river. Umankas up to 5 m high, gently descending to the swampy floodplain of the river. Lifting material in the form of stucco ceramics is found on an area of \u200b\u200b500 x 100 m. In the places of the greatest accumulation of lifting material, stationary excavations were carried out in 1979, as a result of which an area of \u200b\u200bapprox. 1600 sq.m, on which 4 dwellings, 3 outbuildings, 8 utility pits and 3 outbreaks were found (Fig. 2).

Dwelling No. 1 was cleared in the northern part of the settlement, closer to the swampy floodplain of the river. It was a sub-square semi-dugout with rounded corners measuring 4.1 x 3.9 m and 1.1 m deep from the modern surface. The walls of its pit are vertical, the flat floor is leveled. Near the southeastern wall, closer to the eastern corner, there was an oval adobe hearth with a diameter of 0.8 m. Its surface is slagged in places. In the corners of the dwelling and in the center of each of the walls, oval or round pits were cleared from pillars with a diameter of 10-20 cm.In the central part of the floor of the dugout there was the same pit 10 cm in diameter and 20 cm deep.At 0.6 m from the southwestern wall of the pit , an oval utility pit with a diameter of 0.55 m and a depth of 0.25 m from the floor level was cleared (Fig. 4: 3). In the dark filling of this dwelling, a large amount of stucco ceramics, a fringe of a gray-polished Chernyakhov pottery bowl, an iron knife, an iron sickle, a link from a copper chain, pieces of iron slag, a bone "burnished" were found (Fig. 8: 7-15; 13)

Dwelling No. 2 was located 44 m south-east of semi-dugout No. 1. It was an almost square semi-dugout with rounded corners, measuring 3.8 x 3.7 m and 1.1 m deep from the modern surface. It is oriented almost to the cardinal points. The pit walls are vertical, the flat floor is carefully leveled. In the eastern corner, at the floor level, there was a collapse of a stove-heater with an adobe hearth. Near the southern corner there was an oval ledge dug up to the floor level with dimensions of 1.3 x 0.2 m. In the ledge there were large burnt stones, apparently from the collapse of the furnace. In the central part of the floor there was a pit, round in plan, with a diameter and depth of up to 20 cm. A utility pit with a diameter of 0.55 m and a depth of 0.25 m was cleared nearby. Its walls are vertical, the bottom is flat (Fig. 3: 4). Among the dark filling of dwelling No. 2 were stucco ceramics from Penkovskaya, a fragment of a potter's bottom from the neck of the Chernyakhovsky look, a bone puncture, "polished" from the ribs of large animals, an iron object of poor preservation (Fig. 8: 1-3, 5, 6)

Dwelling No. 2 3 was found 22 m south of dwelling No. 2. It was a sub-square semi-dugout with rounded corners and a slightly narrowed west side. The dimensions of the building are 4.7 x 5.3 m, the depth is 1 m from the modern surface. The dwelling is oriented almost to the cardinal points. The walls of its recessed part were vertical, the flat floor was leveled and well rammed. In the central part of the building, closer to the northeastern corner, at the floor level, an adobe hearth with irregular outlines, 0.6 x 0.55 m in size, was traced. Several burnt stones were found near it. In the corners of the pit and in the center of the northern and southern walls, there were pits from the vertical supports (20-30 cm in diameter and depth). Almost in the center of the building, the same hole with a diameter and depth of up to 20 cm was cleared. Closer to the southeastern corner, an oval-shaped utility pit with a diameter of 0.95 m and a depth of 0.35 m from the floor was traced. Its walls are narrowed to a flat bottom (Fig. 4: 4). Among the dark filling of dwelling no. 3, many stucco ceramics were found, a rim from a pottery vessel of Chernyakhov's appearance, a fragment of a millstone, two iron knives, a bone "polish", etc. (fig. 8: 4; 9: 8, 9, 11, 12, 14-17; 13: 7, 8).

Dwelling No. 4 was traced at a distance of 44 m to the west of the previous building. It was a large semi-dugout, close to a square, with rounded corners measuring 6.2 x 5.6 m and 0.9-1 m deep from the modern surface. The building is oriented almost to the cardinal points. Its recessed part had vertical walls and a flat, well-rammed floor. Two clay hearths were cleared at the floor level. The first was closer to the north, and the second to the south wall. They are oval in plan with a diameter of 1.3 m. Between the hearths, approximately in the center of the building, there was an oval lenticular pit 1.1 m in diameter and 15 cm deep from the floor level (Fig. 4: 6). In the dark filling of this dwelling there was a large amount of stucco Penkovo \u200b\u200bcrockery, several clay bikonic spinning wheels, a stone whetstone, "polished" from the ribs of large animals (Fig. 9: 1-7, 10, 13, 15; 13)

Household building No. 2 I was cleared 2.8 m east of dwelling No. 2. It is a deepened sub-rectangular building with rounded corners measuring 2.4 x 1.6 m and 1 m deep from the modern surface. The walls of its hollow are vertical, the flat floor is flattened. The building is oriented with walls to the cardinal points. Several hemp shards and animal bones were found in its light filling. Household building No. 2 2 was located 12.5 m west of dwelling No. 2. The building is rectangular with rounded corners measuring 3.9 x 2 m and a depth of 1 m from the modern surface. Its long axis is oriented from north to south. The earthen walls of the excavation were vertical, the flat floor sloped southward. The light filling of this building contained several molded shards and animal bones. Household building No. 23 was discovered 19.6 m south-east of dwelling No. 1. It is rectangular with rounded corners measuring 2.6 x 2 m and a depth of 1 m from the modern surface. The walls of its pit are vertical, the bottom is flat. The building is oriented with walls to the cardinal points. Several molded shards were found among its dark filling. Household building No. 4 was located 1.5 m north of dwelling No. 4. It was an almost square semi-dugout with dimensions of 3.6 x 3.5 m and a depth of 0.9 m from the modern surface. The walls of her pit were vertical and the floor was flat. In the central part of the building, a small hole, 20 cm in diameter and 15 cm deep, was cleared. The utility hole was located closer to the southeastern corner. It is oval in plan with a diameter of 0.6 m and a depth of 0.2 from the floor level. The walls of the pit are slightly narrowed towards a flat bottom. There were several molded shards in the light filling of this structure.

Pit No. 1 was cleared at a distance of 1.8 m to the southeast of the southern corner of dwelling No. 2. It is almost round in plan with a diameter of approx. 1 m and 1.3 m deep from the modern surface. Its walls narrowed to a flat bottom. No finds were found in the light filling of this pit. Pit No. 2 was located at a distance of 2 m from the western corner of dwelling No. 2. It is oval in plan with a large diameter of 1.35 m and a depth of 1 m from the modern surface. The walls of the depression are vertical, the bottom is flat. A stucco shard was found among its light filling. Pit No. 3 was 1.3 m from the northern corner of dwelling No. 2. The depression is almost circular in plan, 1.4 m in diameter and 1.4 m deep from the modern surface. The walls of the pit tapered to a flat bottom. Its light filling contained molded shards and animal bones. Pit No. 4 was located 1.5 m from the eastern corner of dwelling No. 2. It is oval in plan with a diameter of 1.9 m and a depth of 1.6 m from the modern surface. Its walls are slightly narrowed towards a flat bottom. In the light filling of this hole, molded shards and animal bones were found. Pit No. 5 was located 2 m north-east of utility structure No. 2. It is almost round in plan, 1.7 m in diameter and 1.2 m deep from the present surface. The walls of the pit are slightly narrowed towards a flat bottom. Among the dark filling of the pit were molded shards and animal bones. Pit No. b was found 17 m west of dwelling No. 4. It is oval in plan with a diameter of 1.4 m and a depth of 1.3 m from the present surface. Its walls tapered to a flat bottom. In the dark filling of this depression, many stucco ceramics were found. Pit No. 7 was traced 3 m south of utility structure No. 3. The deepening is round in plan with a diameter of 0.8 m and a depth of 0.9 m from the modern surface. Its walls are tapered to a flat bottom. Several molded shards were found in the pit. Pit No. 8 was located 14 m south-west of pit No. 6. It is oval in plan with a diameter of 1.7 m and a depth of 0.6 m from the present surface. Its walls are narrowed to a flat bottom. In the dark filling of the pit, stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200band a fragment of a granite millstone were found.

Hearth No. 1 was located 11 m north of dwelling No. 2, at a depth of 0.6 m from the modern surface. It was an almost circular pavement of small stones with a diameter of approx. 0.8 m. On its surface there was ash, coals and small Penkov scoops. Hearth no. 2 was cleared at a distance of 6 m southeast of dwelling no. 2, at a depth of approx. 0.6 m from the modern surface. The pavement made of small stones had an ellipse-like shape with a large diameter of 0.9 m, on which there were coals and fragments of hemp ceramics. Hearth No. 3 was found 16.5 m southeast of dwelling No. 1, and at a depth of 0.5 m from the modern surface. The earthen bed was oval in plan with a diameter of 0.9 m.

An ancient ditch 0.8-1 m wide and 1.1-1.3 m deep from the modern surface was explored for a length of more than 30 m. Its walls narrowed downwards. In the dark filling of the ditch, there were individual Penkovo \u200b\u200bshards. Most likely, it was dug up by residents of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlement. It is possible that he separated households No. 1, 4 from households No. 2,3. A similar moat was discovered by us during excavations of an early medieval settlement near the village. Sakhnovki.

19. p. Krasnopolye, Magdalinovskiy district, Dnipropetrovsk region To the north-east of the village, on the shore of Lake Orelishche, the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin in 1970 found molded ceramics with an admixture of chamotte in the dough.

20.s. Limanovka of Zachepilovsky district, Kharkov region In the village above the estuary, on the right bank of the river. In 1970, the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin collected rough stucco pottery and ancient Russian shards.

21. p. Maly Rzhavets, Kanevsky district, Cherkasy region In the center of the village, on the rise of the first floodplain of the left bank of the river. In 1979 the stucco ceramics of Penkovo \u200b\u200bwere collected.

22. p. Mikhailovka, Tsarichansky district, Dnepropetrovsk region At 500-800 m to the west of the Mezhevaya grave mound, the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin in 1970 collected molded Slavic and Scythian ceramics and shards of the Bronze Age.

23.24. from. Novoselitsa, Chigirinsky District, Cherkasy Region In the vicinity of the village V.P. Grigoriev in 1981 discovered two metonoincidences with stucco hemp ceramics. The first one is located at ur. Panskoe. A bronze bracelet with widened ends was found here. The second settlement is located on the left bank of the river. Tyasmin, at ur. Nechayevo.

25 s. Nosachiv Gorodishchensky district, Cherkasy region. In the arable field between the villages of Nosachiv and Tsvetkovo I.P. Gurienko collected fragments of stucco hemp utensils.

26 p. Osipovka, Magdalinovskiy district, Dnipropetrovsk region 1.5 km from the village, on the left bank of the river. Aureli at ur. The beach by the expedition of D.Ya. Telegin in 1972-1974, during the excavation of a settlement of the Bronze Age, explored three quadrangular semi-dugouts (Nos. 1, 3, 9) and a yurt-like dwelling with stucco Penkov material.

The semi-dugouts were rectangular in plan with an area of \u200b\u200b8-13 square meters and a depth of 1-1.6 m from the modern surface. At the floor level, closer to the center of the buildings, there were stone hearths (dwelling No. 3) or hearth spots. In dwelling No. 9, 2 hearth spots were traced. Near the entrance ledge of dwelling No. 3, wooden blocks have been preserved, located at right angles to each other. In the filling of these objects and in the cultural layer, stucco Penkovsky ceramics were put on (Fig. 12: 1-13).

The yurt was an oval structure deepened into the ground 1.1 m from the modern surface, measuring 4 x 2.8 m. In the center, traces of a hearth patch were traced (Fig. 6: I). Among the dark filling of this structure were found stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200band inner handles from clay cauldrons (Fig. 6: 2-14).

27. p. Pilyava, Kanevsky district, Cherkasy region On the territory of the village, on the first low floodplain of the right bank of the river. Rossava, at ur. Tserkovisko in 1979

on an area of \u200b\u200b400 x 50 m, stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200band individual shards of ancient Russian times were collected.

28-30. from. Polstvin, Kanevsky district, Cherkasy region In 1979, three Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements were discovered in the vicinity of the Chela. On the first of them, located on the elevation of the first floodplain of the right bank of the Rossava near the bridge, stucco ceramics of Penkov was collected on an area of \u200b\u200b300 x 50 m. The second is located 200 m upstream from the previous point, on the first right-bank floodplain, occupied by household plots. There, on an area of \u200b\u200b200 x 40 m, stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200bwere collected. The third is located upstream of the river, on the right-bank floodplain, occupied by household plots. Penkovsky ceramics have been collected on an area of \u200b\u200b100 x 50 m.

31. p. Drying Kanevsky district, Cherkasy region. In 1960, excavations were undertaken in the Penkovsky village near the village. Drying on the left bank of the Dnieper. It is located 1 km south of the village, on the right bank of the river. Nut, at ur. The goat's horn, where the serpent shaft is located. The settlement occupies the first above-floodplain terrace of the river 0.7-1.5 m high and is constantly washed away by the river. Excavations uncovered an area of \u200b\u200bapprox. 150 sq. M, on which the remains of 5 dwellings, an outbuilding, 9 utility pits of the Penkovo \u200b\u200bculture and a pit (No. 5) of the Kiev type culture were found.

Dwelling No. 1. Partially preserved remains of a semi-dugout were traced in the coastal edge under the serpent rampart. Its northern corner has been preserved with side dimensions of 1.4 and 1.2 m, the floor, located at a depth of 1.4 m from the present height of the rampart, was leveled and greased

somewhere. Stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200bwere found at the floor level (Fig. 11: 5).

Dwelling No. 2 was found on the coastal cliff 110 m east of semi-dugout No. 1. Its northern part, 3 x 2.25 m in size and approx. I m from the modern surface. The structure is oriented with corners to the cardinal points. The walls of the boiler were vertical, the floor was flat. In the eastern corner, a cylindrical pit 1.5 m in diameter and 0.3 5 m deep from the floor level was cleared. The second pit was located closer to the center of the dwelling, at a distance of 1 m from the northern corner. It is oval in plan with a diameter of 0.6 m and a depth of 0.1 m from the floor level. Its walls are vertical, the bottom is flat. In the dark filling of this building, a large amount of stucco ceramics was found, sometimes with a stuck-on roller under the rim. Other finds include an iron chisel and a ceramic spindle (Fig. 11: 9; 13). Dwelling No. 3 was found on the edge of the coastal line 19 m east of the semi-dugout No. 2. Its northern part with dimensions of 2.9 x 1.25 x 1.25 m, which was oriented with its walls to the cardinal points, was preserved. The floor, with traces of clay-based grease, was at a depth of 1.4 m from the modern surface. In the surviving part of the building, three utility pits, oval in shape, with a diameter of 0.35 to 0.65 m and a depth of 0.1-0.25 m from the floor have been cleared. Large and small burnt stones lay on the floor, and along the northern wall of the excavation there was a depression 0.2 m wide. It is possible that this is the trace of the lower log of the log walls of the semi-dugout. In the black filling of this semi-dugout, stucco ceramics of Penkovo, ceramic slags and a bronze ring with curled ends were found (Fig. 11: 9: 13: 2).

Dwelling No. 4 was discovered in the eastern part of the settlement, separated by a recently formed outflow. The semi-dugout is quadrangular in plan with dimensions of 4.4 x 3.9 m and a depth of 0.9 m from the modern surface. It is oriented with corners to the cardinal points. The floor is leveled and oiled with glia. In the corners and in the center of each of the walls of the pit, holes were cleared from the wooden supports of the frame walls. They are oval or round in plan with a diameter of approx. 0.3 m and a depth of 0.1-0.6 m from the floor level. In the northeastern part of the building, there was a circular utility pit with a diameter of 0.3 m and a depth of 0.15 m from the floor level. Near the southwestern wall, at the floor level, an oval clay-walled furnace with a diameter of 0.6 m was cleared out. Stones from the furnace disassembled in antiquity are scattered on the floor (Fig. 4: 2). The filling of dwelling no. 4 contained stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200band a fragment of a round glass "eyelet" bead (Fig. 11: 6-8)

Dwelling No. 5 was cleared at the base of the rampart, 25 m north-west of dwelling No. 1. The semi-dugout was square in terms of shape, measuring 4 x 4 m and 1 m deep from the modern surface. It is oriented by walls to the cardinal points. In the northeastern corner, in a small depression, an adobe hearth with low sides was recorded, oval in plan with a diameter of 1.1 m. Closer to the southern side of the building, a round pit for household purposes with a diameter of 1.4 m and a depth of 0.1 m was cleared. Among the finds from this dwelling, molded Early Penkovsky ceramics prevailed (Fig, 10: 1-5).

Household building No. 1 was located 12 m west of dwelling No. 2, on the coastal edge. Only its northern oval side with dimensions of 2 x 1.25 m has survived. The floor, located at a depth of 1.35 m from the modern surface, is leveled and slightly oiled with clay. At the western wall there was a utility pit, round in plan, 0.5 m in diameter and 0.3 m deep. Its walls are vertical, and the bottom is flat. At a distance of 0.4 m from the center of the northern side of the pit, there was a square pit from the pillar, 0.2 and 0.2 m in size and 0.3 m deep from the floor level. Stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200bwere found in the filling of the building.

Pit No. 1 was excavated on the edge of the coastline 57 m east of dwelling No. 1. Judging by the preserved part, it was circular in plan with a diameter of 1.25 m and a depth of 1.4 m from the modern surface. In the dark filling of this pit were several molded shards and animal bones. Pit No. 2 was cleared on the coastline 19 m to the east of pit No. 1. The depression is round in plan with a diameter of 1 m and a depth of 1.25 m from the modern surface. Its walls narrowed slightly towards the lenticular bottom. Several molded shards were found in the filling. Pit No. 3 was discovered 2 m north of dwelling No. 2. It is oval in plan with a large diameter of 1.3 m and a depth of 1.5 m from the present surface. Its walls are vertical, the bottom is flat. In the filling were found molded shards and animal bones. Pit No. 4 was located 25 m northeast of dwelling No. 1. It was cylindrical in shape with a diameter of 1 m and a depth of I, 4 m from the modern surface. Several stucco shards were found in the filling. Pit No. 6 was found 1.2 m to the north-east of pit No. 5. It is cylindrical, 0.6 m in diameter and 1.3 m deep from the present level. There were small stucco shards in the filling. Pit No. 7 was located 0.6 m north-west of pit No. b. A cylindrical deepening with a diameter of 1.3 m and a depth of 1.1 m from the modern surface. Small stucco shards were found in the filling. Pit No. 8 was located on the northern side of dwelling No. 5. It is oval in plan with a large diameter of 1.7 m and a depth of 1.1 m from the modern surface. The depression had vertical walls and a flat bottom. There were several molded shards in the filling. Pit No. 9 was traced 0.1 m east of pit No. 8. It is cylindrical in plan with a diameter of 1.7 m and a depth of 1.2 m from the modern surface. Several molded shards lay on its flat floor. Pit No. 10 was discovered at a distance of 2.7 m to the east of pit No. 9. The depression is oval in plan with a large diameter of 1.1 m and a depth of 1.25 m from the modern surface. Several stucco shards were found in the filling.

Hearth no. 1 was near the water, under the sod layer to the east of dwelling no. 4. An oval stone pavement, approx. 1 m was at a depth of 0.2 m from the eroded surface.

Iron-smelting furnace No. 1 was located near the rampart, on the edge of the coastline 22 m north-west of dwelling No. 5. From it, remains of slagged adobe walls and pieces of iron slag were preserved, which were at a depth of 0.3-0.5 m from modern surface. In the center of the collapse, at a depth of 0.5 m, traces of severe soil burning are visible. It is most likely that the forge was destroyed during the construction of the serpent shaft.

32. p. Trushki of Belotserkovsky district, Kiev region In the funds of the Belotserkovsky Museum of Local Lore, there is a molded biconical pot with a bumpy surface and admixtures of grit in the dough (Fig. 11: 16). It was found by local residents in the vicinity of the village. Trushki.

33-34. Uman city, Umansky district, Cherkasy region In its vicinity, intelligence agencies in 1979 discovered two Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlements. The first of them is located on the territory of the Zvenigorod suburb, on the right bank of the river. Palenki when owning the Kotlomyevka brook, ur. Butok. In the area of \u200b\u200bthe floodplain up to 3 m high, occupied by household plots on an area of \u200b\u200b150 x 40 m, stucco Penkovsky ceramics were collected. 1.5 km southeast of the Uman crushed stone plant, on the right bank of the Umanka River, adjacent to a boggy meadow, on an area of \u200b\u200b150 x 40 m, there is a stucco Penkovo \u200b\u200bceramics. A large settlement with materials from the culture of Luki-Raikovetskaya adjoins the Penkovo \u200b\u200bsettlement.

35 s. Tsarychanka Tsarychansky district of Dnepropetrovsk region 1 km southeast of the tank farm, on the right bank of the river. Oreli expedition of DY.Telegin in I960, while digging the area, found rough molded Slavic ceramics.

36. p. Tsybli Pereyaslav-Khmelnitsky district, Kiev region On the territory of an abandoned village, on both sides of the stone church, in the cliffs of the left bank of the river. Dnieper (up to 3 m high) in 1980, a large amount of stucco ceramics from Penkovo \u200b\u200bwas collected.

Notes

1. Berezovets D.T. Settlements of the streets on the Tyasmine river // MIA. No. 108.1963.p. 145-

208; Linka N.V., Shovkoplyas A.M. Early Slavic settlement on the Tyasmin river // MFA. No. 108. S. 234-242.

2. Berezovets D.T. Op. Cit. S. 186-192.

3. Tretyakov P.N. Finno-Ugrians, Balts and Slavs on the Dnieper and Volga. M.-L.,

1966, pp. 244-247; V. V. Sedov Origin and early history of the Slavs. M., 1979. C. 119-133.

4. Smshenko A.T. The words "yani ta ikh sushchi in steppe Podshprov" (II-XIII centuries)

Kshv, 1975.S. 71-103.

5. Rutkovskaya L.M. On the stratigraphy and chronology of the ancient settlement near the village. Stetsovki on the Tyasmina River // Early Medieval Eastern European Antiquities. L., 1974.S. 32-39.

6. Rutkovskaya L.M. Op. Cit. S. 22-39; E.A. Goryunov Some questions of the history of the Dnieper forest-steppe Left Bank in the V - early VIII centuries. // CA. 1973. No. 4. S. 99-112.

7. Prikhodnyuk OM Archaeological monuments of the "yaks of the Middle Transdniestria" I "XIХ century n.e. Kshv, I960. S. 12-71.

8. Prikhodnyuk OM The words "yani na Podilli (VI-VII centuries AD) Kshv, 1975, p. 36