Dogs parachutists of the second world war. Special forces of the armies of the world British paratroopers

Churchill and the appearance of the commandos

In the face of the approaching battle for England, the new British Prime Minister Winston Churchill harbored no illusions about the reasons for the defeat of the French. In a letter to his government minister, Anthony Eden, he wrote: “I got the impression that Germany was right to use assault units during World War I and now ... France was defeated by a disproportionately small group of well-armed soldiers from elite divisions. The German army, following the special forces, completed the capture and occupied the country. "

England in the 30s was very different from Germany. In Germany, the victory of the National Socialists led to a political revolution. Violation of the terms of the Treaty of Versailles contributed to the development of special forces there. In England, the conservative military hierarchy, not fond of the new, frantically held on to the classical methods of warfare. For example, Marines were prohibited from developing the skills required for airborne assault. At the same time, the Air Force vehemently opposed every proposal to form parachute formations.

Video: British Commandos (SWAT)

In the summer of 1940, Churchill sent several letters to senior officers and chiefs of staff of the army, air force and navy. He demanded that they stop sabotage and start creating special forces, which he gave different names (for example, "assault groups of cavalrymen", "leopards", "hunters"). Defense officials eventually settled on the term "special service battalions." Until the end of 1944, official information referred to "SS units" (special service). Public opinion, Churchill and the soldiers themselves, however, preferred the word "commando." It was suggested by an officer from South Africa who organized the first groups. As in the case of the Boer commandos of 1900, the first task of the British soldiers was to lead the partisan movements against the occupying forces, to help in the formation of these forces. Her Royal Majesty's Press Agency worked hard to compile, print and distribute among the British brochures such as: "The Art of Guerrilla Warfare", "Manual for the Leader of the Partisans", "How to Use Explosives."

However, Churchill was not going to postpone the use of commandos until the moment the Germans landed on the English coast. On June 9, 1940, he sent the following note to the chiefs of the headquarters of the combat arms: “The entire defensive doctrine killed the French. We must immediately begin work on the organization of special forces and give them the opportunity to operate in those territories whose population sympathizes with us. " Two days later, he demanded "strong, proactive and persistent work on the entire coastline occupied by the Germans."

At the end of the summer of 1940, twelve commando formations were organized. Each had a strength of about a battalion. Volunteers from the entire British army joined their ranks. Only the soldiers of the Marine Corps, which were in the stage of expansion to the division, were not allowed to join the special forces. This was partly due to the fact that Churchill wanted to keep them as a strategic reserve in case of need to protect London from the German landing. All officers had the opportunity to recruit only the best volunteers. They had to be young, energetic, intelligent people with good transport driver skills.

The first volunteers came from different branches of the military and kept their uniforms with the corresponding patches. They lived most often in apartments, not in barracks. The officers of each unit until early 1942 were personally responsible for the soldier training program. As a result, the level of their skills was very different.

The actions of soldiers who participate in an air or sea assault require the coordination of actions of all branches of the military. Therefore, on July 17, Churchill appointed his old friend, Admiral Roger Keyes, hero of the Zeyebrugge raid in 1918, as head of Joint Operations. However, things did not go as well as Churchill wanted. Preparation of amphibious assault forces is associated with lengthy training and the construction of special landing craft. It would take many months even with the support of the British military headquarters, and Keyes, unfortunately, did not have support among the military hierarchy. General Alan Brook, who soon became Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and his deputy, General Bernard Paget, were convinced that it was a mistake to form commando-type formations separate from the regular forces. Keyes quarreled with them, as a result of the necessary equipment he never received, and all his proposals for the operation of special units were rejected.

The only exception was the large-scale raid aimed at destroying the blubber factories in the Lofoten Islands (Norway) on March 3, 1941. The commandos met no resistance, and this raid was essentially a military training exercise. The operation had only propaganda value. The newsreel, reflecting this operation, was successfully shown in different countries. The period of inactivity that reigned after the raid on Lofoten contributed to the demoralization of the commando units. Keyes again began to quarrel with Alan Brook and the Admiralty. As a result, Churchill, who was tired of these skirmishes, removed Keyes from his post on October 27, 1941.

Combat operations of British special forces (commandos) in World War II

Parachutists in Operation Colossus

Unlike the German command with its ideas of "lightning war" through tank breakthroughs and airborne assault forces, the leadership of the British armed forces has long denied the importance of the airborne troops. It was only under pressure from Churchill that the RAF command organized the training of the first battalion of paratroopers in May 1940.

It took place at Ringway airfield, near Manchester. These locations were outside the range of the Luftwaffe aircraft and were therefore not attacked. The group of instructors was led by Air Majors Louis Strange and John Rock. They had to face serious difficulties. Aviation Ministry officers strongly opposed the creation of parachute units. The resistance was expressed primarily in the poor material supply of the school in Ringway. She was allocated 6 obsolete Whitworth-Whitney-1 bombers, not adapted for landing, and an insufficient number of parachutes. In addition, there were objective difficulties: the technique of landing paratroopers with weapons and equipment was not developed, there were no training manuals, and there were not enough experienced parachuting instructors.

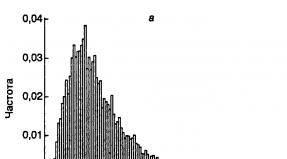

The first jump at Ringway took place on June 13, 1940. It immediately became clear that jumping through a hatch in the floor of an aircraft requires great dexterity, composure and just luck, since even a small mistake could cost life. Instructors have shown the commandos many times how to safely slide off the fuselage, but the cadets, struggling to overcome their fear of flying, acquired the necessary skills very slowly. Of the 342 parachutists sent to training courses and passed the medical commission, 30 categorically refused to make at least one jump, 20 were seriously injured, and 2 died - only 15% of the total. Nevertheless, over 10 weeks of intensive training, the cadets made 9610 jumps, no less than 30 for each paratrooper.

Combat operations of British special forces (commandos) in World War II

Out of 290 graduates, on November 21, 1940, they formed the 11th SAS battalion (special airborne service). Major Trevor Pritchard became the battalion commander, Captain Jerry Delhi and Senior Lieutenant George Paterson became the deputies. The battalion consisted of three battle groups, commanded by Captain Christopher Lee, First Lieutenants Anthony Dean-Drumond and Arthur Jowett.

Back in June 1940, the Air Force command decided to carry out an air raid to destroy the Tragino aqueduct, located on the slope of Monte Vultere in the Italian province of Campania. This aqueduct supplied fresh water to the cities of Bari and Taranto, the bases of the Italian navy. Anyway, he provided drinking water for more than two million people living in the neighboring province of Apulia. However, in the process of developing a raid plan, it became clear that an aerial bombardment of an object located high in the mountains was unrealistic. Then they decided to entrust her to parachutists. At the same time, they wanted to test their combat effectiveness. On January 11, 1941, the plan for the operation, code-named Colossus, was officially approved.

It was entrusted to the special unit "X" of the 11th SAS battalion under the command of Major T. Prichard. Based on aerial surveys in Ringway, a model of the aqueduct and the surrounding area was built. The plan provided for the release of troops 800 meters from the target. The viaduct was to be blown up by seven sappers, led by Captain D. Delhi, and the rest served as cover. After completing the assignment, divided into four groups, the soldiers were to retreat to the mountains, and from there to the Gulf of Salerno, 100 km from the place of the action. Further evacuation was planned aboard the Triumph submarine from the submarine fleet based in Malta. The submarine sailed to the mouth of the Sele River on the night of February 15-16, 1941 to pick up the commandos.

The operation began on the night of February 7, 1941. Six Whitney bombers took off from Middenhill airfield in Suffolk and landed in Malta after 11 hours of flight (2200 km). On February 10, 1941 at 22.45, 36 soldiers took off from the Luka airfield. They jumped from planes in the area of \u200b\u200bthe Tragino aqueduct. The ice covering the fuselages prevented two additional aircraft from dropping containers of weapons and explosives. As a result, out of 16 such containers dropped by the rest, only one was found. Two more Whitneys bombed the city of Foggia to disguise the target of the operation. The landing zone was correctly identified by 5 aircraft, and the group of Captain Delhi (7 people) landed 5 km from the target, unable to reach it in time. The rest, after a hard trek through deep snow in the mountains, reached the aqueduct. By order of Major Pritchard, 12 people began to plant explosives. It turned out that the entire structure was reinforced with concrete, and not brick, as claimed by aerial reconnaissance from Malta. The loss of 14 containers and ladders in deep snow created additional difficulty. The soldiers had only 350 kg of explosives at their disposal. According to the plan, they were going to blow up three supports and two spans, but in the current situation they were limited to one support and one span. Fuses were connected, and at 0.30 min. half of the aqueduct flew into the air. In this remote and almost deserted mountainous region, despite all the difficulties, it was relatively easy to complete the mission. From two destroyed water pipelines, water flowed and flowed into the valley. At the same time, E. Dean Drummond's group destroyed a small bridge on the Tragino River in the Ginestra region.

Immediately after completing the task, Major Pritchard divided the participants in the operation into 3 groups and ordered them to withdraw. 29 people were going to cover about 100 km in 5 days. They walked only at night, during the day they hid in gorges and forests. It turned out that it is very difficult to move around this area without any support from the population. When retreating, the soldiers of Unit "X" left footprints in the snow. During a raid organized by the Italian police, in which local residents forcibly participated, on February 14, Major Pritchard's group was surrounded on one of the hills, and the paratroopers laid down their arms. The same fate befell the other two groups, and within three days all the participants in the operation fell into the hands of the enemy. However, many of them soon escaped from captivity, including Senior Lieutenant E. Dean-Drummond, who managed to get to England.

Although Operation Colossus did not cut off the military ports of southern Italy from water supplies, it ended in success for paratroopers. They have proven their combat effectiveness. The operation also confirmed that it is relatively easy to carry out a raid deep into enemy territory, but it is very difficult to remain on it for a long time without the help of the local population.

Winston Churchill and paratroopers

The operations of the commando units in Italy and Norway were evaluated differently. The Air Force and Navy Command considered them unsuccessful. The soldiers from the regular units chuckled, claiming that the commando's famous physical training was only suitable for "clashes with the fair sex." However, Churchill was convinced of the correctness of the chosen path. Wishing to cheer up the parachutists, he visited them in April 1941 at Ringway airfield, where he watched a demonstration of parachute jumping, shooting and hand-to-hand combat. Sitting in the flight control tower, he talked with the crews of the bombers in which the parachutists flew. Hearing on the intercom that the next young soldiers refuse to jump, he asked them to talk to him on the radio. The astonished paratroopers, having heard a stern reprimand from their beloved prime minister, obediently approached the hatch and jumped out of the plane without further protests.

Winston Churchill: pioneer of the education of British commandos (special forces) in World War II

The exercise at Ringway Airfield marked a watershed in the relationship between paratroopers and aviation. The Air Force leadership realized that the prime minister would not give in and finally began to treat the airborne units as comrades in arms, and not as competitors for the supply of military equipment and weapons. In addition, at a special conference, paratroopers were presented with reconnaissance data on the actions of German parachutists, their training, equipment and tactical and operational tasks. At the end of April 1941, the headquarters of the Royal Air Force began the systematic construction of the airborne troops, but in the corresponding document noted: "I would like to have real evidence of the capabilities hidden in this new type of weapon." This argument, although not the one the British dreamed of, soon emerged.

On the morning of May 20, 1941, German paratroopers landed troops on the airfields of Crete: Malem, Kania, Rethimo and Heraklion. True, they suffered heavy losses, but thanks to a fortunate coincidence for them, they managed to capture the airfield at Maleme. Despite the British fire, transport planes carrying ammunition landed on the runways, and gliders with the famous Alpine riflemen from the 5th Mountain Division landed on the beaches near the city. Soon the landing forces reached a numerical superiority in the area. The British began to retreat towards the mountains. Ten days later, the remnants of the Cretan Allied garrison of British, Greeks, Australians and New Zealanders fled from the small fishing ports in the south of the island. The day before, the British command in London had been convinced that the success of the Germans was impossible. The headquarters officers pointed to the huge losses among the paratroopers and the inevitable drop in morale after the bloody massacre they experienced during the landing. However, this was only the inevitable price of the first amphibious operation of a huge scale. The British underestimated the courage, comradeship and bravado of the Germans. The capture of Crete was a major success for German weapons and, at the same time, a powerful incentive for the deployment of British special forces.

Enraged and humiliated, Churchill summoned the Air Force Chief of Staff, placed him at attention and issued a non-negotiable order: “In May 1942, England should have 5,000 paratroopers in its shock formations and another 5,000 at a fairly advanced stage of training. ...

Combat operations of British special forces (commandos) in World War II

Churchill's green light opened up previously unknown opportunities for the British special forces. He could now count on the help of the army, navy and aviation, and specialized scientific organizations began to develop equipment, weapons and various devices for sabotage.

The training has become much more intense. Churchill also revised the command staff, removing officers with conservative views from the leadership. He was looking for young, dynamic, capable, balanced and at the same time educated people. “I want them to turn over the liver from looking at them at the teachers at Sandhurst,” Churchill said venomously, referring to the famous military academy.

The king's cousin Lord Louis Mountbatten, a hero of naval battles, became the head of the British commandos, the heir to Keyes as head of the United Operations. At the same time, Major General Frederic Browning, an officer of the Grenadiers of the Guards and husband of the famous writer Daphnia Du Maurier, became the commander of the paratroopers. Both were characterized by free thinking, devoid of a bureaucratic touch, the ability to find contact with subordinates. Not surprisingly, their personal prestige was followed by the development of the units entrusted to them, in which volunteers were now eager. (At the end of 1942, Browning already had two trained paratrooper brigades.) However, Mountbatten's activities resulted in administrative restrictions on the recruitment of commandos in the army. After Alan Brook's protests, he could only build his forces from the Marine Corps.

Following the organizational revolution, changes began in the training system. First of all, they abandoned training jumps from Whitney's unsafe bombers. They were replaced by tethered balloons. This has produced amazing results. In November 1941, the 2nd and 3rd battalions of paratroopers were formed. During their training, out of 1773 cadets, only two refused to jump, 12 were injured, but not a single person died. The fear barrier has been shattered.

Two months later, Mountbatten ordered the establishment of a training center at Aknacarry, at the old Castle of Cameron of Loch Eile, Scotland. Special forces soldiers underwent all-round physical training there, fire and special training, a 3-kilometer run in full gear, climbing the castle walls, waterborne assault forces, overcoming assault strips - all this under real fire from firearms - which made it possible to select the really best. Those who could not stand it returned to the army. Commandos were trained in the use of communications, explosives, knife and poison. The sabotage business was taught by scientists with university degrees. In addition to the British, soldiers from other countries, including Poles and Czechs, studied at Aknacarri.

Intense training strongly rallied the personnel of the paratrooper and commando units. Wanting to reinforce a sense of common belonging, Browning introduced special hats, different from the usual army ones: a chestnut-colored beret with an attached badge depicting the Greek hero Bellerophon, racing on the winged horse Pegasus.

Raids on Waagze, Bruneville, Saint-Nazaire

The first large-scale commando raid took place on December 27, 1941. The target was the Norwegian port city of Vaagsee. The commandos, backed by the navy and bombers, fought for every street. The Germans fiercely resisted, but could not compete with the commandos. The British lost 71 people; killed, wounded and taken prisoner 209 German soldiers. German ships with a total displacement of 16 thousand tons located near the coast were sunk. With Vaagze, a new stage began in the actions of British special forces.

Later, two operations were carried out, which rivaled Witzig's attack on Fort Eben-Emael, and in some ways achieved more. On February 28, 1942, during the night, a group of Commando C of the 2nd Paratrooper Battalion (nicknamed "Jock's Company" because there were many Scots among the soldiers) landed at Bruneville, a coastal French village containing the latest German radar. The team was led by the newly appointed Major John Frost. The paratroopers quickly coped with the Germans who did not expect an attack, dismantled as many electronic units as they could carry, and the rest of the devices were photographed and blown up. Then they returned to the shore, from where they were taken by the waiting landing barges. The Germans managed to grab only two signalmen who got lost while returning to the assembly point. Lord Mountbatten was delighted. In his opinion, the operation in Bruneville was the best one ever.

Combat operations of British special forces (commandos) in World War II

A month later, it was the commandos' turn again. On the night of March 27, 1942, the old destroyer Campbeltown, which after modernization looked like a German Meve-class destroyer, sailed at the head of a small flotilla of motor boats into the upper Loire, directly to the dry dock at Saint-Nazaire. This dock was the only place on the entire French coast where it was possible to repair the German giant - the battleship Tirpitz. The plan to pass off Campbeltown as a German ship was a success. The Germans identified him only at a distance of 2 thousand meters from the dock and immediately opened fire. At that moment, the ship raised a white flag and, moving in the upper reaches of the river at a speed of 20 knots (37 km / h), hit the dock gate. The echo of the blow was still heard in Saint-Nazaire when commandos began to jump out of Campbeltown. Their task was to lay explosives under the hydraulic systems and pumps. All the time they were under the fierce fire of the German military posts. The motorboats, their only means of return, were destroyed.

The landing troops tried to break through the streets of the city and take refuge in the forests, but suffered very high losses. Of the 611 commandos who took part in the raid, 269 never returned. Five paratroopers were awarded the Victoria Cross. More awards for one operation in England were received only once - in 1879 for the heroic defense of Roorks Drift.

On the morning of March 28, the Germans were still pondering the purpose of this raid. Campbeltown is firmly wedged between the dock gates. They weighed several hundred tons and were not badly damaged by a powerful blow. At 10.30 am, when 300 German sappers and sailors were examining the old destroyer, 4 tons of a charge, placed in a cement-filled hold, exploded. German casualties were even greater than those of the British, and the dock itself was so destroyed that it was only possible to repair it in the 50s.

The fearless operations in Bruneville and Saint-Nazaire made a huge impression also because they coincided with the heavy defeats of the Allies. Singapore surrendered to the Japanese on February 15, and Rangoon fell on March 9. Success in France softened the bitterness of failure on other fronts. Popular English writers V.E. Jones and S.S. Forester used the events for their adventure stories, albeit with a lot of embellishment. In the summer of 1942, the film The Commandos Attack at Dawn was shot in Hollywood based on Forester's book, which was a huge box office success.

Failure of Operation Jubilee

In a state of euphoria caused by the successful raid on Saint Nazaire, the combined operations leadership (led by Mountbatgen) began planning a large-scale operation, code-named Rutter. Dieppe was the target. It involved commandos, recently organized rangers, British and American paratroopers and a brigade formed from the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division. Due to bad weather conditions, Operation Rutter was postponed. However, soon the plan of the raid was reanimated under the code "Jubilee". The main points were the same. The only difference was that the airborne assault was abandoned, and this greatly offended the parachutists.

The destroyed Matilda tank that covered the British and Canadian commandos during the landing in Dieppe in Operation Jubilee.

On August 19, 1942, before dawn, five squadrons of landing barges, accompanied by destroyers, approached the coast of France. At 4 o'clock in the morning, the landing force ran into a German convoy. A naval battle ensued, during which the British sank two German escort ships. The element of surprise, which constituted the main part of Operation Jubilee, was out of the question. At 5:00 am on the rocky beach leading to the main esplanade of Dieppe, the largest barge with Canadian forces from the Canadien Royal Regiment landed. However, the Germans, who knew about the night skirmish, awaited an attack and within a few hours almost completely destroyed the helpless Canadians. Smaller units of commandos and rangers landed on the flanks - west and east. Their task was to destroy the enemy's coastal batteries and divert his attention from the main forces. In general, this stage of Operation Jubilee can be considered successful, the 3rd Assault Airborne Detachment under the command of Major Peter Young, a veteran of the raids on the Lofoten Islands and Waagsee, attacked in the Petit Berneval region east of Dieppe, tying up the enemy forces for several morning hours. At this time, the 4th Assault Airborne Force, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Lord Lovat, destroyed an artillery battery west of the city.

Captured British.

Operation Jubilee ended in failure, however. Of the 6,100 people who took part in the landing, 1,027 died, and 2,340 were captured (mostly Canadians). The losses of the commandos and rangers were relatively small. Out of 1,173, only 257 soldiers died. Experienced commandos were critical of this venture. Operation Jubilee was too big for a raid and too small for an invasion. It showed, however, that in large-scale operations, special forces should be landed on the flanks, where they should quickly destroy powerful defensive posts and enemy batteries. Dieppe's experience was later used in planning Operation Overlord (Overlord)

Special Forces in the Middle East

Public attention focused on operations in England and the English Channel area. However, already in the summer of 1940, some soldiers of the British forces located in the Middle East began to be transferred to special units. They had a great influence on the development of future special forces, not only in England, but also in other countries. The beginning was not easy. In June 1940, the command in the Middle East, acting on orders from White Hall, established a Commando Training Center in Egypt. It was placed in the Kabrit area near the Big Bitter Lake. The soldiers who ended up there turned out to be a good starting contingent, but their equipment was poor, and their training left much to be desired. In the winter of 1940-1941. commando units took part in unsuccessful operations behind the Italian defense lines in Ethiopia, as well as in attacks on the Italian-occupied Dodecanese Islands. The raids ended in failure, and the soldiers were taken prisoner by Italy. Enraged, Churchill demanded the creation of a commission of inquiry, the findings of which were strictly classified until the post-war period.

Combat operations of British special forces (commandos) in World War II

Battalions "Layfors"

However, there was a need to intensify the activities of special forces in the Mediterranean basin. This led to the relocation of three commando battalions to the Middle East under the leadership of Colonel Robert Laycock (from his name the battalions were named). These forces arrived in Suez in March 1941 by sea around the Cape of Good Hope.

Laycock tried to restore the reputation of the special forces, including the best commandos in his units, and transferred the rest to parachute and motorized formations. However, his efforts were in vain. From April to June 1941, Layfors took part in three operations, during which they were almost completely destroyed.

The first attack was launched on 17 April on the outskirts of Bardia, deep in enemy territory. The Layfors landed and launched an offensive against the Italian fortifications, but on their return they did not find their way to the assembly point. The second attack was carried out by two "Layfors" battalions, which landed on the northern coast of Crete on 21 May. The goal is to capture the airfield in Maleme. "Layfors" were on the coast already during the retreat of the main British forces to the south of the island and played the role of covering troops. The commandos defended the evacuation of the majority of the garrison, but suffered heavy casualties themselves. No more than 179 soldiers made it to Egypt. On June 8, the last battalion "Layfors" conducted an operation on the coast of French Lebanon, controlled by the troops of the Vichy government. The goal is to support the British forces advancing from Palestine. The battles were very difficult, the battalion lost 123 soldiers, a quarter of the entire composition. On this "Layfors" ceased to exist. On June 15, 1941, General Waivell, commander of the British forces in the Middle East, issued an order to disband them.

Desert Long Range Groups

For a naval power like England, the Mediterranean served as an excellent corridor through which attacks could be launched against targets along the coast of Africa. British officers who served in Egypt in the thirties considered the obvious possibility of operations from the Libyan Desert, gradually turning into the sea of \u200b\u200bsand of the Sahara Desert. Major Ralph Bagnold, an officer of the Royal Communications Service, conducted research and topographic surveys of the Egyptian deserts and the Libyan desert in the 1930s.

At Waivell's initiative in June 1940, Bagnold organized a special reconnaissance force LRDG (Long Range Desert Groups). The British army did not have enough combat vehicles, so Bagnold bought 14 one and a half ton trucks from the Chevrolet company in Cairo. He got 19 more cars, begging "sponsors" for evening drinks or borrowed from the Egyptian army. However, the conservative English army did not want the soldiers of the regular units to volunteer in special forces, in which improvisation was a daily practice. Then, in a difficult situation, Bagnold became interested in the New Zealand and Rhodesian troops, and this offended the British, whose "sports spirit" did not put up with such humiliation. In the end, desert patrols were formed from the English guard and the Emenri (reserve) regiments.

British commando in typical outfit. British special forces in World War II

The first operation was extraordinarily impressive and became widely known in the British headquarters. Between December 26, 1940 and January 8, 1941, an LRDG patrol traveled 1,500 kilometers southwest of Cairo. Having overcome the powerful unexplored dunes, the soldiers reached the Fezzan plateau in southeastern Libya, where the Italian garrisons were located. There they joined forces with the Free French, which marched from Chad in a northeasterly direction. The attack by the combined Anglo-French forces on the Italian garrison in Murzuk took the enemy by surprise. The losses of the attackers were small. However, the commander of the Free French column, Colonel D "Ornano, died. He was replaced by the deputy Colonel Comte de Hauteclok, better known by the military pseudonym Jacques Leclerc, which he took for himself so as not to endanger the family that remained in France. The attack on Murzuk was the beginning of his combat path, later crowned with the staff of the Marshal of France.

The raid on Murzuk confirmed the operational capabilities of the Light Desert Troops. Therefore, the next action was planned. However, at the end of March 1941, the German Afrika Korps under the command of Lieutenant General Erwin Rommel arrived in the area of \u200b\u200bthe fighting between the Italian and British forces. As a result of the offensive of the combined Axis forces, the British were forced to retreat to Egypt. At the same time, their command issued an order on the deployment of LRDG units on the Egyptian-Libyan border, at a safe distance from the Desert Fox soldiers. The LRDG commandos spent most of the summer of 1941 there.

The Hunt for Desert Fox by Erwin Rommel

The spring and summer of 1941 brought humiliating defeats to England in the Mediterranean basin. But in addition, this period was marked by the actions of commando units. As mentioned above, most of them were merged into an impromptu Layfors structure (teams 7, 8, Bottom of the Metropolis and two units formed on the spot mainly from Jews and Arabs, as well as from former soldiers of the international brigades who fought in Spain). The Layfors Brigade was sent to fight for Crete (May 1941). Here, scattered among separate groupings of Australian, New Zealand troops, battalions of Maori, Greeks, the soldiers shared the fate of those who fought against the German airborne assault. The largest unit, under the command of Colonel Laycock, served as a cover for the withdrawal of the remnants of the British corps from the island.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel is the target of British commandos. British special forces in World War II

The few lucky ones who escaped the bullets and precipices in the mountains and finally reached the fishing village of Sfakion, from where the royal fleet was supposed to pick them up, found it empty, without a single ship. As a reward for their dedication and heroism, they were left to the mercy of the enemy - a typical story of cover formations sentenced to death to save the main forces. Even then, the commandos were not discouraged. Under the leadership of the indefatigable Laycock, repelling the attacks of German patrols, they quickly repaired several abandoned barges and began a perilous voyage towards Egypt (about 700 km). Fortunately for them, there were no strong winds.

The return of the presumed dead commandos did not save them from disbandment. Some were transported to England, where they were attached to other special forces, some became instructors. Someone was sent to the garrisons of Malta, Cyprus, Lebanon and Egypt. Many returned to their native units. In conditions of deep defense, with a chronic shortage of people to hold the extended front in Libya, the command saw no reason to allow entire battalions of extremely experienced soldiers only occasionally to demonstrate their capabilities in widely advertised operations.

Only a few small detachments of commandos survived. The largest (59 people), was engaged in reconnaissance and belonged to the 8th Army. The commander was the same Laycock, who was trying to revive his recently powerful brigade.

The fate of this unit, almost symbolic in number, remained precarious. Voices were heard in favor of disbandment. Not surprisingly, his staff was constantly thinking about how to raise their prestige. In 1941, the exit consisted only in battles. This means that an important military operation should have been prepared and carried out, the consequences of which would have been felt by the entire British army in this area.

Soon, the plan came to the fore by Laycock's deputy, Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Keyes, the son of the then chief of joint operations. Keyes proposed to simultaneously attack several targets in Libya, located far from the front line. The main goal is a villa in the town of Beda Littoria. Intelligence has established that this was the seat of Rommel, the commander of the notorious "African corps". The commandos hoped that the removal of the unusually gifted general would have a devastating effect on all German and Italian forces in Africa. Laycock had no problem agreeing to such an operation. He was promised help.

Combat operations of British special forces (commandos) in World War II

Preparation began. Above all, a thorough reconnaissance was needed. A "long-range desert group" was connected to it - commandos engaged in raids across the Sahara, often in enemy uniforms or in Arab clothing. The soldiers of this unit and its commander, Captain Haslden, managed to get to the immediate vicinity of the buildings where the German headquarters were located. They gave a detailed topography of the area, took photographs of houses, described the regime and habits of security, patrol routes. This inspired hope for success.

An important problem was the way the assault groups approached the target. The parachute landing was impossible - there were not enough airplanes, and the people of Laycock did not receive appropriate training. Penetration from the side of the desert, as Haslden and his people did, was also considered unrealistic - there were no skills for a long stay in the desert. There was only a sea route, on which they agreed. The transfer was decided to be carried out on submarines, using the experience of the commandos Courtney - specialists in kayak operations (CBS). He dispatched four experienced scouts and equipment to instruct.

The attack on Rommel's residence was to involve 59 commandos, divided into four groups. It was planned to simultaneously destroy three targets: the Italian headquarters, a reconnaissance center in Appolonia and communication centers.

On November 10, in the evening, two miraculously received submarines - Torbay and Talisman - left the port in Alexandria. Inside, in the cramped space with the team, there were 59 commandos, various weapons, kayaks and other military equipment.

When the boats reached the destination from which the landing was to begin, in accordance with the plan, two kayakers, Senior Lieutenant Ingles and Corporal Severn, sailed to land first, in order to establish contact with Hasdelden's people who were waiting on the shore. It happened on November 14 in the evening. Soon, signal lights flashed from the shore, and the disembarkation could begin. Unfortunately, the weather, which was still favorable to the British, began to deteriorate. The wind in the direction of the coast grew stronger, foam appeared on the waves. Conditions did not facilitate travel on rubber pontoons. Laycock had serious concerns before the landing. In the end, not wanting to disrupt the schedule of the operation, he gave the order to begin. The first to move were the commandos from the submarine Torbay. Four of the six inflatable boats were washed into the sea by the waves. For several hours they were caught and again prepared for descent. As a result, the landing of the group under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Keyes turned into a five-hour struggle with the growing storm. Not only time was lost, but also a significant part of military equipment and food supplies.

When it was the turn of the Laycock group from the Talisman, dawn was already approaching, natural disguise was ending. The landing should have been interrupted, but Laycock decided to take the risk and convinced the commander of the submarine that he was right. His group was even less fortunate. The boats were thrown, they overturned, emptying all the inventory. Most of the soldiers, barely alive from fatigue, returned to the rescue board of the Talisman with the help of the crew. There was not enough time, the horizon was brightening, the boat could be discovered at any moment, which would have disastrous consequences not only for her, but for the entire operation.

Combat operations of British special forces (commandos) in World War II

In total, 36 commandos were on the Libyan coast, slightly more than half of the planned staff. The soldiers, together with the Arab guides, immediately began to remove the traces of the landing. The rubber boats were buried in the sand, heavy weapons and food supplies were transferred to the nearest ravines and caves. Only now could they seek shelter for themselves. They turned out to be hollows in the rocks, flooded with streams of rain. Very soon the fortunes of Rommel's future winners were regrettable. Soaked and exhausted at sea, they had no protection from the cold and rain. Lilo grew stronger, and the storm did not allow the others to land.

In such circumstances, Laycock decided to carry out the operation on a limited scale with the available forces. He divided them into three groups. Keyes and Captain Campbell were in charge. Together with 17 soldiers, they were to kill Rommel. Senior Lieutenant Cook and six commandos were ordered to paralyze communications in the vicinity. Laycock with the rest of the people had to remain in place to guard the landing site, equipment and receive reinforcements. On November 15, at 19:00, assault groups led by the Arabs moved towards the enemy headquarters.

Keyes' group at night from 16 to 17 reached a point 15 km from Beda Littoria. The next day people spent in rocky niches, hiding from the enemy, and even more from the rain. Snapping their teeth and barely holding back from coughing and cursing, they were warmed by their own warmth.

In the evening, with new guides, but with even worse forebodings, they began to move towards the target of the attack. This time they rejoiced in the rain and darkness that hid them, drowned out their footsteps and probably dulled the guard's vigilance. A kilometer from Trouble, the moon appeared in the gaps of the clouds. In its light, the Bedouin guide pointed to the coveted target - a complex of buildings surrounded by fluffy palms and a ring of thickets. The commandos said goodbye to him (he never wanted to go further) and began to sneak up to houses in small groups.

At this stage, an incident occurred that could destroy all plans: Captain Campbell heard approaching voices. He listened and froze with his people. A minute later they realized that there were numerous Arabs serving in the Italian army. They were only seconds apart from shooting. Campbell jumped out of the darkness and in the purest German began to "scold" the patrol for walking near German apartments, noise, etc. The embarrassed Arabs, making excuses in several languages, quickly retreated, being sure that they were disturbing the peace of their German ally, who should not be irritated.

Five minutes before midnight, the commandos took up their starting positions. Keynes, Campbell, Sergeant Terry, and two others took over as terminators. They went to the parking lot and the garden that surrounded Rommel's villa, intending to eliminate those who would flee through the windows. Three had to turn off the electricity. Four were left on the driveway with machine guns. The other two wanted to stop the officers from the nearest hotel with fire.

Subsequent events developed with lightning speed. Keynes signaled with his hand. Together with his four, he rushed to the front doors of the villa, but did not notice a single sentry. The door would not open. Campbell joined again with his impeccable German. He knocked energetically, and, posing as a courier with urgent news, demanded to be admitted. He had a knife in his right hand and a pistol in his left. The sleepy sentry seemed to feel his fate and reluctantly opened the door, at the same time raising the machine gun. The knife could not be used through the narrow gap. Since the German suspected of something managed to remove the weapon from the safety lock, they had to shoot. The German collapsed with a terrible noise onto the marble floor. The commandos jumped over it and found themselves in a large hall. Two officers ran from above, pulling Walter out of their holsters. Terry laid them down in a burst of Thompson. The officers were still rolling down the stairs, and Keynes and Campbell were already at the door of the next room. They started shooting through the door, but there was no answer. The lights went out at the same time.

From the next room the Germans also opened fire through the doors. Keynes fell dead. Grenades were thrown inside, then a machine gun was fired. A similar procedure was repeated in the rest of the premises, until we were convinced that there was not a single living German inside the villa. There was no time to find and identify Rommel. Outside, gunfire was growing from all sides. Campbell, who took over command after Keyes's death, ordered the retreat and bombardment of the building with grenades to cause a fire. At the last minute of the fight, he was wounded in the leg, and he decided to surrender so as not to detain the entire unit. Now command was taken over by Sergeant Terry, who organized the retreat superbly. He managed to gather all the other commandos, set fire to and destroy the unfortunate villa, and then break away from the pursuit, taking advantage of the darkness and pouring rain. The experienced sergeant was well-versed in unfamiliar terrain and, after a march, in a day, led his subordinates to the site of the recent landing, where a worried Laycock awaited them.

The return of the strike group with relatively low casualties was overshadowed by the death of the beloved Case. Cook's group did not return. All consoled themselves with the probable death of Rommel. The next day passed in a double expectation of the rest of the commandos and favorable weather for boarding the boat. Torbay signaled that the wave is too high. The sailors sent some food on a drifting pontoon, which was driven to the shore by the wind.

In the afternoon of November 21, the Germans and Italians appeared in the vicinity, and immediately found the British. A fierce battle ensued, in which the commandos' chances were minimal, as they were first cut off from the sea and then from their only escape route. Leikoku could only go inland. He wanted to take refuge in the uninhabited mountains of Jebel al-Akhdar, confuse the pursuit, and then make his way across the front line. However, the enemy, who had a significant advantage, upset the colonel's plan. Only he and Sergeant Terry made it to the mountains. The rest were killed or taken prisoner. Laycock and a friend, after 41 days of wandering through the desert and mountains, reached the line of British troops. Only they survived. However, the most tragic thing was that the commando strike missed the mark. During the assault on Littoria, Rommel was not in Libya at all. He flew to Rome a few days before to meet his wife and calmly celebrated his fiftieth birthday. Judging by German materials, British intelligence was mistaken. Rommel never had a residence in Beda Littoria. He never even came there. Beda housed the main housing administration of the German corps. Its personnel were almost completely killed, but it was not worth the death of one of the best units of the British commandos.

Others learned from the mistakes of the operation in Beda Litgoriya. Thanks to the comrades who remained lying on the Libyan coast, they survived after new battles, in which they soon avenged Keyes and his soldiers.

Creation of SAS and new tactics

Meanwhile, events took place in Cairo that pushed the British special forces to new actions. In June 1941, a two-meter tall officer came to General Ritchie's office with an unexpected visit, limping, and presented a plan to destroy the Axis air force in Libya. This officer was David Stirling, formerly of the Layfors forces. He limped from injury during training jumps. Stirling's plan was bold, full of fantasy and insane enough that the new commander of the Allied forces in the Middle East found it feasible. Stirling proposed to create a unit of 65 soldiers from the remnants of Layfors. They were to descend by parachute near enemy airfields, lay time mines and go to certain assembly points, from where they would be picked up by LRDG patrols. Stirling's SAS (Special Air Service) unit was named to confuse German intelligence. He started preparing.

In the fall of 1941, England had three elite units in the Middle East: the commando, the LRDG and the SAS. Churchill issued an order to reorganize these troops and reappointed Laycock as Commander. He was then a brigadier, but Churchill always used the term "general." And in November 1941, they launched Operation Crusader. In this major counteroffensive, special forces units were used in operations deep behind enemy lines. The end result was unfortunate, but the conclusions and consequences played the same role as the raid on Dieppe.

The saboteurs of the 55th division of the SAS on the day after the landing of Laycock tried to land from the air at airfields in the Ghazali area. The very winds that blocked the evacuation of the commandos scattered the SAS paratroopers across the desert, and only 21 of them found a gathering point where LRDG vehicles were waiting for them.

As a result of Operation Crusader, Rommel's forces were driven back from Cyrenaica in December 1941. Ultimately, the commandos did not play a significant role in the battles with his troops. Early the next year Rommel launched a counteroffensive, during which the British were forced to retreat to the El Alamein area. Rommel stretched his supply lines hundreds of kilometers away from the fortress at Tobruk.

An attempt to attack Tobruk failed. Joint action by the commandos and the LRDG forces stalled. The Germans fiercely defended the port, inflicting heavy losses on the attackers. The British fleet lost two destroyers, and 300 of the 382 commandos who took part in the raid.

The defeats at Tobruk and at Dieppe served as a bitter lesson and forced the headquarters to draw appropriate conclusions. It was necessary to develop new tactical concepts based on saving the lives of soldiers. One of them was used even earlier during a raid on the Tamet airfield near Benghazi. During that operation, the SAS and LRDG units worked closely with each other, and each of the formations played an important role. LRDG soldiers in camouflaged vehicles were waiting near the airfields. Meanwhile, Stirling, at the head of a small group of saboteurs, planted time mines under 24 aircraft and detonated everything.

A radically new approach to sabotage, adopted in June 1942, gave startling results. During a raid on Bagush airfield, the commander of the assault team, Paddy Maine, went into a rage when the mines planted by his group at the airfield did not explode. Enraged, Main and Stirling drove in their jeeps directly to the airfield and opened fire with machine guns. 7 German combat aircraft were destroyed. In July, SAS forces adapted dozens of American jeeps that had arrived, each with two coaxial Vickers machine guns or Browning heavy machine guns. Each jeep could fire 5,000 rounds per minute with the simultaneous fire of all machine guns.

A period of success began for the SAS and LRDG units. They penetrated into the rear of the enemy and attacked the airfields of the Axis troops. The operations involved up to 18 jeeps in a row. Their machine guns could fire tens of thousands of shots per minute. Before Rommel began to withdraw to the Maret Line on the Tunisian-Libyan border, he lost 400 aircraft in such raids. Buried under their wreckage was the hope of catching up with the air power of the Allies.

Operation Torch

Rommel began withdrawing troops to Tunisia on November 4, 1942. On November 8, the Allies launched Operation Torch. It was supposed to land airborne and naval troops on the coast of North Africa, controlled by the collaborationist French government of Vichy, and set up a trap for the retreating Germans. The commandos and rangers were given a mission similar to the one they had not completed during the operation at Dieppe. However, this time they achieved much greater success, the 1st Ranger Battalion attacked an artillery battery defending the beach in the city of Arzew in western Algeria (this city is one of the targets of the operation). Meanwhile, 2 groups of commandos landed in the Gulf of Algeria and destroyed the coastal fortifications.

In contrast to the fierce resistance at Dieppe, the French defense in North Africa was rather weak and fragmented. In Operation Torch, paratroopers performed a very important task; They were supposed to capture French air bases, the main communication centers and help the Allied forces in the attack on Tunisia, the 509th paratrooper battalion was delivered directly to the air force base in Senia, near Oran, using 39 C-47 aircraft. The commander of this risky operation, Lieutenant Colonel Raff, received information from Allied intelligence that the French would not resist. Therefore, he made the decision to land directly on the runways. As with the localization of Rommel's headquarters (during Operation Crusader), the intelligence was wrong, which led to disaster. The French met the attackers with such powerful fire that Raff and his men were forced to make an emergency landing at a nearby salt lake. Therefore, the merit of the capture of Senya belongs to the ground forces. Then the situation improved, on November 8, the 3rd battalion of paratroopers landed in Beaune, 250 km west of Tunisia. Three days later, the 509th battalion, recovered from a "friendly meeting" in Senia, landed at the airfield in Tebes (200 km from Beaune), on the border between Tunisia and Libya. Here the Allies were accepted as liberators.

Combat operations of the British special forces SAS (commandos) in World War II

The 1st battalion of paratroopers, which landed on November 16 in Suk el Arba (120 km west of Tunisia), was received much less favorably. Fortunately, the British officers managed to get hold of the situation in time. They instilled in the commander of the French garrison (3,000 soldiers) that they were the forward units of the two panzer divisions in the vicinity.

On November 29, the 2nd battalion of paratroopers under the command of John Frost (who had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel since the raid on Bruneville) landed near Oudn air base, 15 km from the city. Although the Germans had already left the base, it was not only the white minarets that could be seen from the nearby ridge. Tunisia and its environs were literally packed with mechanized and tank formations of the Axis forces. Threatened by the advancing Germans and Italians, the 2nd Paratrooper Battalion began to retreat on 30 November. The retreat of the English units did not resemble the stampede of a gazelle pursued by a herd of lions. It was the retreat of a wounded lion in front of a herd of hyenas. Fighting stubbornly, on December 3, the 2nd battalion of paratroopers reached the allied positions. He lost 266 men, but his line of retreat was literally strewn with destroyed Axis tanks and hundreds of Italian and German corpses. For the first, but not the last time, the 2nd battalion of paratroopers opposed the seemingly inexorable logic of war.

By the beginning of December 1942, it became clear that despite the efforts of the paratroopers, the Allies had no chance of capturing Tunisia on the move. The command stated with regret that the war in Africa would not end in the near future. However, the strategic position was not bad. The Axis forces, squeezed in a small area (430 km from north to south), no longer had a chance to conduct major counter-offensives.

Now British commandos and paratroopers were to fight on the front lines like regular infantry. This situation was repeated many times over the next two years. On March 7, 1943, the first clash took place between a battalion of German paratroopers under the command of the legendary Major Witzig and the 1st battalion of paratroopers. Initially, German soldiers inflicted losses on the British, but the latter launched a successful counterattack and forced the Germans to retreat.

Allied commandos and paratroopers fought on the front lines until April 1943, with a total of 1,700 casualties. The soldiers in red berets showed extraordinary courage and, perhaps, that is why the enemy called them "red devils". British skydivers are still proud of this nickname.

While the British were operating on the front lines, their American counterparts were carrying out very dangerous reconnaissance and sabotage raids. Each attack could end tragically, since many thousands of Axis soldiers were concentrated in a small area, readily supported by the Tunisian Arabs, who were hostile to the Allies.

On December 21, 1942, a platoon of soldiers from the 509th battalion landed in the El Jem area, in southern Tunisia, with the task of blowing up a railway bridge. The bridge was blown up, but the return was a nightmare. The soldiers had to go 170 km of mountainous terrain and desert. Of the 44 soldiers participating in the raid, only eight survived.

Even the most experienced "pirates of the desert", attached to the British 8th Army, who were advancing from the southeast, were in trouble. So, a SAS patrol under the command of David Stirling himself, heading for reconnaissance in the Gabes Gap area in southern Tunisia, was discovered by the Germans and was captured. True, Stirling managed to escape, but he was captured 36 hours later.

The LRDG patrols were more fortunate. One of them, composed of New Zealanders under the command of Captain Nick Wilder, discovered a clear passage between the hills to the west of the Mareth Line. Soon the passage was named the captain. On March 20, 1943, Wilder led 27,000 soldiers and 200 tanks through it (mostly from the 2nd New Zealand Mechanized Division). These formations surrounded the Maret Line from the west, marking the beginning of the end of the Axis forces in Tunisia and all of North Africa.

The Parachute Regiment (also called "British Paratroopers"), established by Sir Winston Churchill in 1940, after the end of World War II participated in more than 50 campaigns and deservedly occupies its rightful place among the most prestigious parts of Britain.

With only 370 men, the first British airborne unit was formed first from the personnel of the 2nd detachment. However, its ranks quickly replenished with volunteers, and, once in Tunisia, the paratroopers of the 2nd Airborne Brigade, as the unit began to be called from July 1942, soon earned the Germans the nickname "die roten Teufel" - "red devils".

In 1943, the brigade landed in Sicily; later it became known as the 1st Airborne Division. Meanwhile, the 6th Airborne Division was formed in England, which played the role of a battering ram during the Allied landings in Normandy in June 1944. In August of the same year, the 2nd separate brigade (recruited from the volunteers of the 1st division) was dropped over Provence in order to cut the communications of the German troops. At the end of September, paratroopers of the 1st division, together with the Polish brigade, landed in the Arnhem Hell. Then the Red Devils distinguished themselves in Operation Varsity, which paved the way for the Rhine crossing. "

Although the post-war demobilization significantly thinned the British airborne forces, the parachute regiment soldiers continued to defend the honor of the Union Jack flag around the world: paratroopers were deployed in Palestine (until 1947), in Malaysia, fought on the Suez Canal near Port Said (1956) .), Cyprus (1964), Aden (1965) and Bornso. From 1969 to 1972 they were used in a very dubious way in Northern Ireland as internal troops. In 1982, during the Falklands Conflict, after two battalions of the parachute regiment clearly demonstrated to the whole world that the British airborne assault was still worthy of the glory of their famous predecessors, the heroes of Tunisia and Arnsma, they again found themselves in the center of attention and recognition.

British paratroopers, like all British infantry, are equipped with the SA-80 5.56mm combat system, which includes the L85A2 assault rifle ("individual weapon") and the L86A2 light machine gun ("light support weapon"). This weapon showed itself well on the shooting range, but in practice it turned out that it is quite capricious, it does not withstand frequent parachute jumps, and the paratroopers take it with them only on combat operations. To combat enemy armored vehicles, Milan missile launchers are used - a weapon more powerful than that of conventional infantry units.

Until 1999, three battalions of the parachute regiment (1st, 2nd and 3rd) belonged to the regular British army, and two more (4th and 10th) belonged to the territorial forces. Two of the three regular battalions of the parachute regiment, on a rotational basis, were part of the 5th Airborne Brigade, where, alternately, they were used as an advanced airborne battalion group and an airborne battalion support group. In 1999, the brigade was disbanded and at the present time the parachute units of Britain are represented by 2 battalions (2nd and 3rd battalions), which make up the Parachute Regiment, which is part of the 16th Air Assault Brigade.

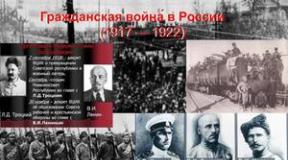

Dutch Operation (1944) (codenamed "Market Garden" - "Vegetable Garden") - Allied military operation, conducted from September 17 to September 25, 1944 in the Netherlands and Germany during World War II. In the course of the operation, the largest airborne landing in history was carried out.

The plan of the operation belonged to the British Field Marshal B. Montgomery and was approved by Eisenhower. The Allied plan was to bypass the Siegfried Line by advancing north into the Arnhem area, capturing bridges over the Meuse, Waal, Lower Rhine, and turning into the industrial regions of Germany. The seizure of Dutch ports was supposed to solve the supply problem. In total, the advancing mechanized units had to overcome about a hundred kilometers from the town of Neerpelt to Arnhem, while crossing at least nine water obstacles. For convenience, the entire corridor was divided into three sectors, which received their names from the names of large cities located in these sectors - Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem. Each of them was assigned to one of the parachute divisions.

The German side gathered the retreating units, brought in reinforcements and built defenses along the Rhine in order to prevent the Allies from entering Germany.

According to the plan, which received the name "Market", the paratroopers had to land on a narrow "carpet path" in the southeastern part of the Netherlands on the Eindhoven-Arnhem section. Removal of drop sites from the front line - 60-90 km. The main goal is to capture bridges over the rivers Dommel, Aa, Meuse, Wilhelmina Canal, Meuse-Waal Canal and further to the Rhine.

The main forces of the 30th corps were supposed to advance on Eindhoven, Nijmegen and Arnhem to connect with the landing force.

the main strategic goal of the operation - opening the way for the invasion of Germany through the north-west of the country - was not achieved. However, the operation ensured the advancement of the Allied ground forces for a considerable distance deep into the territory of the Netherlands. The 101st and 82nd US Airborne Divisions consistently, by capturing bridges, ensured this advance, but the bridge in Arnhem, captured by British and Polish paratroopers, really turned out to be "too far" for the allies (according to unconfirmed reports, the phrase belongs to General Browning ). Arnhem remained in the hands of the German troops.

Due to the fact that the Dutch operation of September 1944 ended in an obvious strategic failure, Montgomery admitted in his post-war memoirs that "Berlin was lost to us when we could not develop a good operational plan in August 1944, after the victory in Normandy."

Paratroopers of the 1st Parachute Battalion, 1st British Airborne Division on the morning of September 17, 1944

Paratroopers of the British 1st Airborne Division signal to transport planes on the bridgehead in the Dutch city of Oosterbeek)

Parachutist of the British 1st Airborne Division with the Sten Mk. V on a plane before being dropped into the Netherlands

German machine gun crew from the 3rd Luftwaffe Parachute Division, armed with a captured American Browning M1919A4 machine gun, in position in Osterbek, a suburb of Arnhem (Arnheim / Osterbeeck)

A column of the StuG III self-propelled guns of the 280th assault gun brigade (Sturmgeschütz-Brigade 280) of the Wehrmacht moves along the street of the town of Oosterbeek, west of Arnhem, September 19, 1944. During heavy fighting in this sector, British troops were driven back to the Lower Rhine

German tank Pz.Kpfw. IV Ausf. H hit by British paratroopers in Arnhem

Captured German soldiers captured by paratroopers of the 1st British Airborne Division in Arnhem. Left to right: a Dutch activist who helped the Nazis, a Kazakh and two Poles. Kazakh was one of three prisoners of "Russian" from the 363rd artillery regiment of the Wehrmacht

German soldiers in battle with British paratroopers in Arnhem, September 17, 1944

Luftwaffe auxiliary captured by British paratroopers in Arnhem

The body of a German soldier killed by British paratroopers in Holland. The photo was taken, apparently, at the checkpoint of some military facility: you can see a sign with the text in Dutch “No entry. Art. 461 of the Criminal Code ”, which indicates the presence of a guarded object, which was attacked by paratroopers. Therefore, in the photo - the killed sentries

A column of the 2nd Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment of the British Army enters the Dutch town of Oosterbeek along the Utrechtsweg road

British soldiers escorting a group of German prisoners during Operation Market Garden

German self-propelled guns StuG III of the 280th assault gun brigade (Sturmgeschütz Brigade 280), the 9th SS Panzer Division "Hohenstaufen" at the intersection of Bovenover and Onderlangs streets in Arnhem, during the battles with the British paratroopers of the 2nd Battalion of the British South American , South Staffordshire Regiment). Soldiers inspect the last building occupied by the British. This vehicle at the beginning of the day during the battle was hit by a grenade from the PIAT anti-tank grenade launcher, which left a dent on the left side of the ACS.

German paratroopers move into combat position along Arnhem Street, September 17, 1944

German self-propelled guns StuG III of the 3rd battery of the 280th assault gun brigade (3./StuG.Brgd.280) and support grenadiers at the damaged hospital building of St. 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment) September 19, 1944. During the battle, the British were forced to retreat

The grenadiers of the Kampfgruppe Möller enter the museum grounds in Arnhem on Utrechtseweg. The museum building housed the positions of the British 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment

Paratroopers of the 7th and 8th platoons of the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment are surrendered to the grenadiers of the Kampfgruppe Möller in the museum area on Utrechtseweg in Arnhem. In the foreground, a German 2-cm FlaK 38 anti-aircraft gun crushed by armored vehicles.

Captured British paratroopers from the 1st Airborne Division walk past a German StuG III SPG in Arnhem. Photo by Erich Wenzel

Collapse of a house in Arnhem after the end of the fighting, September 1944

The landing of paratroopers of the US 82nd Airborne Division from C-47 Skytrain aircraft during Operation Market Garden.

In the foreground, the landing gliders WACO CG-4A "Hadrian"

Gliders "Waco" (Waco CG-4) of the 101st US Airborne Division, concentrated on the airfield before the start of Operation Market Garden

Aerial photography of landing gliders on the field during Operation Market Garden

Panorama of the mass landing of paratroopers during Operation Market Garden, September 17, 1944

1st Allied Airborne Army lands in Holland

Allied 1st Air Force paratroopers boarding a C-47 Skytrain prior to Operation Market Garden

American gliders WACO CG-4A "Hadrian" on a field in Holland during Operation Market Garden. Visible in the sky are the American C-47 Skytrain transport aircraft, towing gliders. September 18, 1944

German SPAAG Sd. Kfz. 251/17 with the calculation in the Dutch town of Plasmolen

Two British soldiers at the wall of a house in a Dutch town

Calculation of the Vickers heavy machine gun from the 7th Northumberland Royal Fusiliers of the 59th Staffordshire Infantry Division in a trench in a cornfield near the Dutch town of Someren

A column of British armored vehicles from the 2nd Battalion Welsh Guards moves across the bridge over the Waal River in the city of Nijmegen during Operation Market Garden. The column is moving British tanks "Cromwell" (Cromwell). In the foreground is the British Universal Carrier. September 21, 1944, photographer Norman Midgley

British paratroopers fire from an Ordnance ML 3-inch mortar at a position near the Dutch town of Oosterbeek. September 21, 1944, photographer Dennis Smith

British war photographers and cinematographers Sergeants G. Walker, C.M. Lewis of the 7th Parachute Battalion (Pegasus emblem) and a resident of the Dutch town of Oosterbeek at lunch on the hood of a jeep

British paratrooper Rumsey fires a 75mm M1 light field howitzer on the outskirts of the Dutch town of Arnhem, photographer Dennis Smith

A crew of a 6-pounder 57-mm anti-tank gun (QF 6 pounder 7 cwt 57mm anti-tank gun) with its own name Gallipoli II from the 26th anti-tank platoon of the 1st British parachute division is firing at the Pz.Kpfw flamethrower tank. B2 (FL) 740 (f) (captured French flamethrower tank Char de bataille B1) from the 224th Panzer Company of the Wehrmacht (Panzer-Kompanie 224.) in the forest on the outskirts of the Dutch town of Oosterbeek, September 20, 1944

A soldier of the 1st British Parachute Division, armed with an American-made M1 carbine, on the destroyed porch of the Hartenstein Hotel in the Dutch town of Osterbek during a battle with German soldiers. September 23, 1944, photographer Dennis Smith

Headquarters Captain of the 1st British Parachute Division David McCombe (1906-1972) fires a 9.65-mm Enfield No. 2 revolver (Enfield No. 2 Mk.VI, .38/200) through the window of the Hartenstein Hotel "(Hartenstein) in the Dutch town of Oosterbeek

British soldiers carry a wounded man on a stretcher during a battle near the Hartenstein Hotel in the Dutch town of Oosterbeek

German soldiers from the Wehrmacht parachute units exchange ammunition in Plasmolen

British paratroopers at a damaged 76mm 17-pounder anti-tank gun on Stadsgracht in the ruined Dutch city of Nijmegen (Nijmegen, September 20, 1944)

British jeeps on the road near the Dutch town of Osterbek

Sgt. 24th Separate British Parachute Company Jim Travis (left) drinks water from Arnheim residents. September 17, 1944

Dutch nurse treats wounded British parachutists

Arnheim resident Tonia Verbeek gives a glass of water to British paratrooper Private Vernon Smith sitting in a jeep.

German soldiers walk past an American M4 "Sherman" tank that was knocked out and lying in a ditch with a turret torn off as a result of the explosion of the BC

British paratroopers Privates Ron Hall and Bill Reynolds of 6th Platoon, Company B, Captain John Killick's 89th Field Security Section, scouting the boulevard in the Dutch town of Arnheim

British paratroopers of the group of Captain John Killick (far right) from the 89th Field Security Section with a German prisoner on the street in the Dutch town of Arnhem. September 18, 1944, photographer Sam Presser

British paratroopers of the 15th and 16th platoons of C Company of the 1st Battalion prepare to repel a German attack in the overgrown Van Lennepweg in the Dutch town of Oosterbeek

Sergeants J. Whawell and J. Turl of the British Glider Pilot Regiment in search of a German sniper on the school grounds (ULO - Uitgebreid Lager Onderwijs) in the Kneppelhoutweg area of \u200b\u200bthe Dutch town of Oosterbeek

Wounded British soldiers at the entrance to 181 Field Hospital (181 A / L Field Ambulance, R.A.M.C.) at 9 Duitskampsweg in the Dutch town of Wolfheze

Lieutenant of the 1st British Parachute Division D.A. Dolley (right) gives a light to the wounded Major Richard Lonsdale (R.T.H. Lonsdale, 1913-1988, left) after the evacuation from Arnheim

A group of British soldiers evacuated from the Dutch city of Arnheim. On the night of September 25, the remnants of the 1st Airborne Division - about 2,400 people - crossed the Rhine to Nijmegen by boats

A soldier from the 1st British Parachute Division watches a burning jeep, hiding from a German mortar attack, during a battle near the Hartenstein Hotel in the Dutch town of Oosterbeek

German paratroopers, advancing to combat positions, carry weapons and ammunition along the street of a Dutch city

British glider pilot Captain Ogilvie (far left) by a jeep en route to the Dutch city of Arnheim during Operation Market Garden

Two paratroopers from the 1st British division fire at houses with an entrenched sniper from a Vickers machine gun on the outskirts of the Dutch town of Arnheim

British Major General Ronald Urquhart (1906-1968) at the headquarters at the Hartenstein Hotel in the Dutch town of Oosterbeek. Next to the general is the standard of the 7th parachute battalion

British soldiers break down the door of a house on Utrechtstrat in the Dutch town of Arnheim

Soldiers of the 1st British Parachute Brigade use parachutes to signal their transport planes at the headquarters at the Hartenstein Hotel in the Dutch town of Oosterbeek

Pictured from right to left, British cinematographers C.M. Lewis and G. Walker and war photographer Sergeant Dennis M. Smith in the Dutch city of Arnheim

The commander of the 1st British Parachute Brigade, Brigadier (Brigadier - a rank in the British army, according to the position is between colonel and general) Philip Hugh Whitby Hicks, 1895-1967) at the map at the headquarters in the Netherlands

Sergeant of the 1st British Parachute Brigade S. Bennett after crossing the Rhine on September 26, 1944 during the retreat. The soldier threw his clothes while crossing, but kept the Sten submachine gun and helmet

British paratroopers armed with Stan submachine guns make their way through a destroyed house in Oosterbeek

British paratroopers Malcolm and Jury in a trench with a 7.7-mm machine gun "Bren" in battle in the Dutch town of Oosterbeek

Chief of Staff of the 3rd Luftwaffe Air Fleet Lieutenant General Hermann Lukas Plocher (1901-1980) gives orders in the town of Milsbeek. The picture was taken on the morning of September 19, 1944 during the visit of Lieutenant General Plocher to Milsbeek to organize a repulse against the Anglo-American landing forces in their landing zone "N" ("Landing Zone N") during Operation Market Garden

British paratroopers in a C-47 transport aircraft before landing in Holland

Corporal Mills of the 1st British Parachute Division at the grave of the deceased in the Arnheim area

Two German prisoners of war under the escort of a British paratrooper in the Dutch town of Arnhem

Residents of the Dutch town of Oosterbeek watch the paratroopers of the 1st British division and German prisoners

Unsuccessful landing of an American parachutist. The 1st Allied Airborne Army is landing during Operation Market Garden

German soldiers search a British officer from the 1st Parachute Division, who tried to escape, disguised as a Dutch civilian

Captured paratroopers of the 1st British Airborne Division captured by the Germans in the Arnhem area, the Netherlands

A paratrooper of the US 101st Division examines holes in the front plate of a British Sherman Firefly shot down in Erp. The emblem of the 101st division on the soldier's helmet is covered with a censor

The fifth day of Operation Market Garden. British Sherman tanks from the Royal Tank Regiment of the 44th Infantry Division, 30th Corps stand on the Nijmegen-Eindhoven road near the village of Veghel on September 21, 1944. On the left, walking Dutch civilians are watching the British.

The 44th Royal Panzer Regiment was supposed to support the US 101st Airborne Division in the battle to maintain control of the Nijmegen-Eindhoven road ("Hell's Highway"), but moved very slowly due to constant stops

The fourth day of Operation Market Garden. British lorry from XXX Corps exploded after being hit by a German shell on the road from Eindhoven to Nijmegen, nicknamed "Hell's Highway". After this explosion, traffic on the road stopped and cars stopped from the town of Son (Son) in Holland to the Belgian border. In a roadside ditch, Allied soldiers are seen taking cover from German shelling

4th day of Operation Market Garden. Medics from the American 101st Airborne Division and a British soldier from the XXXth Corps squat next to the wounded lying on stretchers in a ditch near the Dutch town of Son. There is a convoy of trucks on the highway nearby, and there is a battle ahead

Forced landing of the American B-24j-150-co "Liberator" bomber of the 845th squadron of the 491st bomber group of the 8th US Air Force.

The aircraft was hit by anti-aircraft fire on 09/18/1944 in the Eindhoven area during an operation to supply the 82nd and 101st airborne divisions of the US Army. The car's right wing was badly damaged, and the commander, Captain James K. Hunter, decided to sit on his belly in the field. But at an altitude of 50 feet, the plane's third engine failed, causing the right wing to hit the ground (this moment is captured in the photo). Despite this, the commander managed to gain a little height, but only in order to crash into trees and farm buildings a kilometer northeast of the city of Udenhout. Only the shooter, Frank DiPalma, survived. He was rescued from the rubble by Franciscan monks, who then sheltered him from the Germans in the village of Huize Assisi, until the British liberated it.

The city of Nijmegen, in the background you can see the bridge over the river Waal, one of the branches of the Rhine Delta. The city center was damaged when a squadron of American bombers, returning from an unfulfilled mission over Germany due to heavy clouds, dropped bombs on Nijmegen, mistaking it for a German city

Paratroopers during Operation Market Garden on September 18, 1944, near Wolfhese railway station in Holland. The parachutist lying in the foreground is armed with a PIAT grenade launcher made for shooting, additional grenades are near the tree. Others are armed with a Bren machine gun and a Lee Enfield rifle. The disassembled small sapper shovel sitting behind him

American parachutists fight street fighting in Weigel

Major General Friedrich Kussin (1895-1944) was the garrison commandant of the city of Arnhem. On September 17, 1944, between 4 and 5 pm, at a fork in the roads of Osterbeijk-Wolfhese, his gray Citroen car was fired upon by soldiers of the 5th platoon of the 3rd British parachute battalion. The general, his driver and orderly were killed on the spot.

Photographer Dennis Smith captured this famous photograph the day after Cussin's death. By this time, the body of the murdered had been abused by scalping it. In addition, insignia, awards and almost all buttons were cut off from the general's uniform.

British Airborne Forces glider