The doctrine of the estate representative monarchy. Estates-representative monarchy as a form of government. Dates, causes and consequences of the emergence of the estate-representative monarchy

Estates-representative monarchy is a form of state government, which is based on the principle of estate representation, which exercises government and the issuance of laws. He remains the central political figure in the state. Estates-representative monarchy was a transitional form from the period of early feudalism to.

The main feature of the estate-representative monarchy was the limitation of the tsar's power to representatives from the estates. World examples:

Estates-representative assemblies were based on a contractual basis. This form was based on the need to come to a general agreement on the adoption of certain laws, setting the timing of taxes and taxes, and so on.

Causes of occurrence

The reasons for the emergence of the estate-representative monarchy:

- The growth of the territory of the state;

- Population growth;

- Complication of the country's governance structure, which necessitated the separation of duties;

- Estates appear (merchants, clergy, peasants, etc.).

At the same time, power remained in the hands of the monarch.

The estates wanted to have direct levers of pressure on the decisions made by the sovereign. Some estates concentrated huge amounts of money in their hands. For example, there have been many cases in history when individual class armies outnumbered the royal ones. The merchant classes could easily give money to support life in the kingdom.

Despite this, there were no guarantees that the sovereign would make an unpopular decision. In this regard, the first prerequisites for the emergence of a class-representative monarchy were created.

Examples in different countries

It should be noted that in the countries of Western Europe, the estate-representative monarchy existed from the 13th to the 15th centuries. In Russia, this period belonged to 1549-1659.

Examples of countries with a caste-representative form of government with their own characteristics:

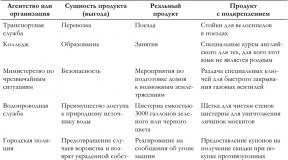

The name of the estate, features | |||

|---|---|---|---|

An "exemplary" parliament. Appeared as a result of the civil war in 1295 | Large spiritual and secular feudal lords | Determination of the amount of taxes, control over senior civil servants, adoption of laws |

|

General staff. Actually acted on behalf of royalty | Nobility, clergy, "third" | The advisory function consisted in close cooperation with the king on the adoption of laws, the introduction of taxes, etc. Could turn to representatives of the royal power with requests and protests |

|

Germany | Reichstag. Gathered twice a year by order of the emperor, had minimal influence | 3 curiae: imperial cities, imperial princes, electors | It did not have the prescribed functions. Often he had an advisory function on various issues (territorial, tax, foreign policy, etc.) |

Zemsky Cathedral. Convened by order of the king | Boyar Duma, clergy, elected noblemen and philistines | Election to the throne of the sovereign, discussion of the most important state issues |

Prerequisites for the emergence of the estate-representative monarchy

Preconditions for the emergence of the estate-representative monarchy:

- Development of commodity production and trade relations;

- Growth in the number of cities;

- The introduction of monetary rent instead of services in kind;

- Cities are freed from feudal dependence and acquire local self-government;

- Unification of estates with inheritance rights.

As a result of these transformations, the preconditions for the emergence of a class-representative monarchy and the simultaneous strengthening of royal power arise.

Algorithm of the estate-representative monarchy

The work algorithm of the estate-representative monarchy in all countries was approximately the same:

- Convocation of estate representation by order of the king / king or on schedule;

- Discussion of the most important state issues in various areas;

- Coming to a "common denominator" between estates;

- Submitting a single solution to the king / king;

- Decision made by the king / king;

- Entry into force after the signature of the king / king.

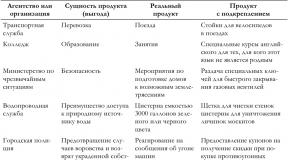

Dates, causes and consequences of the emergence of the estate-representative monarchy

Let's represent it in the form of a table.

Date of occurrence | Cause of occurrence | Effects |

|

|---|---|---|---|

The struggle of the feudal estates with the royal power (catalyst - Civil War 60s XIII century) | It grew into parliament and has survived to this day by transforming the contractual principle into constitutional law |

||

Significant changes in the social and economic sphere | Transition to absolute monarchy |

||

Germany | Weakening of the imperial power, decrease in the effectiveness of the work of the imperial institutions of power | Within the framework of the Holy Roman Empire, the parliament did not grow. After its collapse, it survived as the name of parliament in the German Empire and the North German Confederation |

|

Replenishment of the treasury for military and other needs by inviting representatives of the merchants to the Zemsky Sobor. Calming down citizens. | The transition to an absolute monarchy as a result of the reforms of Peter I |

Period of occurrence and completion

The periods of the emergence and completion of the existence of the estate-representative monarchy.

Date of occurrence | Date of completion |

|

|---|---|---|

England ("Model" Parliament) | To our time |

|

France (State General) | ||

Russia (Zemsky Cathedral) | ||

Rzeczpospolita (Seim) | ||

Netherlands (General State) | ||

Holy Roman Empire (Reichstag) | ||

Croatia (Sabor) | To our time |

|

Spain (Cortes) | ||

Iceland (Althing) |

Modern relevance of the estate-representative monarchy

The relevance of studying the estate-representative monarchy in modern conditions lies in the importance of understanding the problems of modern representative democracy. A deep analysis of that period of time will help in understanding the model of the formation of modern democratic relations.

The opposite of the estate-representative monarchy

Absolute monarchy is, on the one hand, the opposite of the estate-representative monarchy, and on the other, its continuation in most countries.

Absolute monarchy - This is a form of government, which is based on the sole adoption of the most important government decisions by the sovereign. Also characterized by his unlimited power.

In contrast to the estate-representative form of government, where the sovereign's power was limited to estate representation.

Output

In most countries, the estate-representative monarchy did not fulfill its main task - the establishment of a single centralized state. Moreover, the Reichstag in Germany, for example, was the cause of constant internecine wars.

A tougher policy of the autocracy was required. That is why the estate-representative monarchy gave way to absolutism.

There are two forms of government: republic and monarchy.

Estates-representative monarchy – it is a form of feudal monarchy, in which the power of the ruler is combined with the organs of estate representation.

Western European estate bodies mostly formed in XII-XV centuries

Look; Table. European estate representative bodies

In the XVI-XVII centuries. the estate-representative monarchy is replaced by absolutism.

In Russia, the bodies of estate representation were Zemsky Cathedrals.

Zemsky Cathedral – a meeting convened by the tsar to discuss important issues in the life of the country and consisted of the highest church hierarchs ("Consecrated Cathedral"), boyars (Boyar Duma) and high-ranking officials (Duma nobles and clerks and chiefs of orders, butler, treasurer, etc.), as well as in some cases, nobles, townspeople (in the 17th century) and Cossacks (representatives of the Earth).

First convocation - 1549 or 1550

Last:

- 1653 g. – full-fledged,when all the estates of the cathedral were present (about the acceptance of the Left-Bank Ukraine into Russia);

- 24.04.1682 (for approval by Tsar Peter I), 26.05.1682 (for approval by Tsars Peter I and Ivan V) or 1683-1684 (about eternal peace with Poland) - when only representatives of certain estates were invited.

IN composition of cathedrals of the XVI century. included persons according to their official position and belonging to the estate whose question was considered. The sovereign himself listed those estates that he would like to see at the cathedral.

Cathedrals of the 17th century were convened on the basis of tsarist charters sent to the cities to the governors or laborers, with an appeal to send elected people to Moscow for the council (from the townspeople, Cossacks and nobles).

Soon, the elected people no longer represented a certain area, but only informed the tsarist government about the state of affairs on the ground (XVII century).

See: Table. Types of Issues Decided at Zemsky Sobors in Russia in the 16th-17th centuries

Russian Zemsky Cathedrals of the mid-16th-17th centuries should be compared not with contemporary Western European representative institutions, but with the same bodies of the XIII-XV centuries. Because the estate-representative monarchy is formed during the formation of centralized states and helps the monarchs to strengthen their power. In Europe, this is the XIII-XV centuries.

In Russia, Zemsky Cathedrals appeared under Ivan IV, who tried to destroy the last inheritances, and in the 17th century. Zemsky assemblies helped to restore the central government weakened as a result of the Troubles.

Common features of Russian and European estate-representative bodies:

1. Lack of clear laws (charters), regulating the convocation and activities of representative bodies. The exception is England.

2. Conditional estate representativeness due to the absence of representatives of the peasantry... The exception is Spain.

3. Making decisions on foreign policy, tax and legislative activities, as a rule, approving the decision of the monarch.

Features of Zemsky Cathedrals:

1. Lack of clear organizational structure... In Europe, the "third estate" constituted a separate chamber, in Russia, elected delegates discussed issues in groups ("articles"): stewards, Moscow nobles, archers, etc. And the Consecrated Cathedral and the Boyar Duma functioned both as part of the Zemsky Sobor and independently of it.

2. Zemsky sobors are conditional bodies of estate representation due to the final registration of the estates only in 2/2 of the 18th century.(in the Charters of Catherine II).

3. short life span: 100 years (1549/1550–1653) or just over 130 years (1549/1550–1684).

After going through the process of legitimation, i.e. Having received public support, the monarchy ceased to rely on Zemsky Sobors and Patriarch Nikon advised Alexei Mikhailovich not to convene them anymore, since "They belittle the dignity of the king." From the second half of the 17th century. begins to form and takes shape in early XVIII in. absolute monarchy.

Lecture plan

Social structure.

State structure.

Sources and main features of law.

In the XVI - XVII centuries. in Russia, the process of further development of feudal land tenure took place, the local system was strengthened, the process of enslavement of the peasants was coming to an end. The process of strengthening the state took place, its territory expanded; in the second half of the 16th century. the Kazan and Astrakhan principalities were annexed to Russia. In 1654 Russia was reunited with Ukraine. In the XVII century. all Siberia is part of Russian state... Already at the end of the 17th century. Russia was the world's largest multinational state.

The economic development of the country was characterized by the further development of handicrafts associated with the market, the consolidation of handicraft production, the development of manufactories and factories. The development of the economy contributed to the emergence of trade ties, the creation of a single all-Russian market.

The folding of the estate - representative monarchy. Changes in the socio-economic sphere determined the change in the form of government of the Russian state: in the middle of the 16th century, a class-representative monarchy began to take shape. A feature of the development of the monarchy in Russia was the attraction by the tsarist power to solve important issues of representatives not only of the ruling classes, but also of the "upper class of the urban population. Estates-representative monarchy is a natural stage in the development of the feudal state. It took place in France, Spain, Germany. In Russia. the power of the monarch was limited to the Zemsky Sobor.The beginning of the estate-representative monarchy in Russia conditionally dates from the convocation of the first Zemsky Sobor in 1550. There is a dispute around this date.The last Zemsky Sobor took place in 1653. The Zemsky Sobor included representatives of the new feudal nobility (middle and small feudal lords The Boyar Duma was part of the Zemsky Sobor.

The tsarist government could not carry out its functions of power without the support of the Boyar Duma and the Zemsky Sobor as a whole, since the boyar nobility had strong economic and political positions. But due to the gradual consolidation of all groups of the ruling class of feudal lords into a single estate with the same interests and class goals, the role of all groups of feudal lords increased. After the Council of 1653, the Conferences continue to be convened. From the second half of the 17th century, the estate - a representative monarchy began to degenerate into an absolute monarchy. The main factor contributing to this was the formation of an all-Russian market and the further growth of commodity-money relations. It should also be noted that the formation of an absolute monarchy is also due to the complexities of the country's foreign policy position.

The legal status of representatives of the elite of society. The king owned, as before, the palace and black-wooded lands. The cathedral code quite clearly defined the difference in these forms of ownership. The palace lands - the own lands of the tsar and his family, state lands - also belong to the tsar, but as the head of state. The top of the ruling class was made up of the boyar aristocracy. During this period of time, court ranks did not mean an official position, but belonging to a certain layer of feudal lords. Among the court ranks there were distinguished Duma (higher), Moscow, and police officers. All of them were serving people in their homeland, whose privileged position was inherited.

The first Duma and, in general, the court rank was the rank of the boyar. During this period, the boyars made themselves felt, i.e. was announced only to some noble boyar families, while representatives of other families could, by general rule, to receive the rank of boyar only for great services and long-term service.

The second rank was the rank of devious. Through deviousness, less noble people sought boyars.

The third Duma rank was the Duma nobles. They originated from the boyar children.

The fourth rank of the Duma is the Duma clerk. In the Duma sat not only boyars, okolnichy, Duma noblemen and clerks, but also some other court officials.

The less important court ranks belonged to unwise ranks. The Moscow court ranks included the nobles, whose estates under Ivan IV were located in the Moscow district (a selected thousand). They were entrusted mainly with the protection of the state choir and chambers. The police officers consisted of noblemen, who were entrusted with the service in the city. Another group of service people (according to the device - by conscription, and not by inheritance) consisted of clerks, archers, pushers, dragoons, collars, raitors, and soldiers. These officials occupied a middle position between servicemen "in the homeland" and taxing people. The bulk of the service people was determined by "layout", ie. enrollment in regimental lists and appointment to salary, monetary and local. Usually, the sons of the nobility and the children of the boyars were made up for the service, as the state grew and the need to increase the number of service people, sometimes the Cossacks were also made up. The practice of making up service people shows that only children of service people in the 17th century. began to receive regulation. By decrees of 1639 and 1652 it was forbidden to enter the service of children of non-serving people. In 1657 and 1678. it was already ordered to enroll in the service people only the sons of the boyars' children.

The rights of service people. Service people had a number of privilege rights. They were "white", i.e. exempt from payment of taxes. They owned:

The right to own estates and estates;

The (now exclusive) right to enter the public service.

The right to enhanced protection of honor.

A number of privileges in criminal law.

Privileges in the collection of obligations.

Localism. In connection with the development of these privileges, the institution of parochialism acquired particular importance. Establishment of the right of seniority was carried out through complex proceedings. Local disputes brought many complications to appointment to the post, they were especially harmful in appointment to military posts. The complete abolition of parochialism took place in 1682.

Oprichnina. Among the measures of the middle of the 16th century aimed at limiting the old feudal nobility, it is necessary to name the oprichnina. On the issues of the meaning of oprichnina as; in domestic and foreign literature there are very contradictory approaches. The authors proceed from the concept that the oprichnina is not. was an accidental phenomenon, a short-lived episode, but on the contrary a necessary stage in the formation of autocracy, the initial form of its power. The authors share the idea of \u200b\u200bD.N. Alshits that the emergence of the oprichnina did not depend on the will of one person, since the oprichnina was "a concrete historical form of the objective process." In 1565 Ivan the Terrible divided the state lands into zemstvo (ordinary) and oprichnina (special), including in oprichnina - the lands of the opposition princely boyar aristocracy. As a result of the distribution, the confiscated land passed to the service people. The oprichnina turned the estate into the main and dominant form of feudal agriculture. Very significant changes took place with the very concepts of "patrimony", "estate". Patrimonial land tenure became more and more conventional. In 1556, a special "Code of Service" was adopted, according to which equal responsibilities were determined both for the patrimonials and for the landowners to exhibit a certain number of armed people (corresponding to the size and quality of land maintenance). The decree of 1551 forbade the sale of ancient estates to the monastery (for the sake of soul) without the knowledge of the king. And later it was forbidden to exchange them, give them as dowry. The right to inherit these estates was also limited (only direct male descendants could be heirs). A new concept of "paid" or "earned" patrimony appears, i.e. given directly for service or subject to service. The rights of local owners are gradually expanding, and the transfer of land by inheritance is becoming a common phenomenon. Service people were given the opportunity to buy estates. Boyars, as well as nobles, were endowed with local land. There was a process of convergence of estates and estates, the consolidation of the feudal lords into a single estate. This process is quite fully reflected in the Cathedral Code of 1649. The most important forms of land tenure remained ecclesiastical and monastic.

As for the legal status of the clergy, the Sobornoye Ulozhenie limits the growth of church property, categorically forbidding secular feudal lords to bequeath, sell and mortgage the ancestral, favored and redeemed patrimony of monasteries and clergy. Thus, a serious blow was dealt to church land ownership.

Role of the city, urban population. In the XVI - XVII centuries. there is a further growth of cities, trade, crafts, blacksmithing, copper, arms, cannon business are developing. The number of factories and workshops is expanding, the number of the urban population is growing, and its differentiation is increasing. The urban population in the Russian state bore the name of the townspeople. They included the following categories:

The guests are prominent merchants. This title was complained to them for the service and on the terms of service, the financial service (customs and tavern fees). They were exempted from the usual taxes and duties, from the payment of trade duties, had the right to own estates and estates and were subject to the direct court of the king himself.

The living room people are hundreds.

People of the cloth hundreds.

Merchants belonged to the hundreds of the drawing room and the woolen room, who had small capital in comparison with its guests. According to V.O. Klyuchevsky, there were never many guests and merchants of both upper hundreds. So, for example, in 1649 there were only 18 guests, in the living room there were a hundred - 153, in the cloth - 116. Posad people from other cities and black hundreds were divided into the best, middle and young.

At this time, there is an acute differentiation and stratification of the urban population. Among the townspeople, the tops of the wholesale merchants, guests and merchants of the first hundred, who acquired enormous wealth, stand out. In 1649, the government took a number of real measures to streamline the tax relations of the townspeople. According to the Cathedral Code of 1649, it was decided to return to the posadskys the lands, courtyards, and shops that had been torn away by the Belost people.

The city nobility had a number of privileges. She was given the right to lay out and collect all taxes from the townspeople. She received the right to participate in the meeting of the Zemsky Sobor. The largest merchants-guests could buy land with a special royal permission. They received the title of Duma clerks and, in exceptional cases, Duma nobles. Thus, we can conclude that the political significance of the urban nobility grew. All this clearly manifested itself in legal terms. Thus, according to the Code of Law of 1550, under Article 26, a fine was 10 times higher for dishonor of a guest than for dishonor of a "boyar good man." This line was continued and fixed in the Cathedral Code of 1649.

Changes in the legal status of the peasantry. Strengthening of serfdom .. In the second half of the XVI - the first half of the XVII century there was a process of further enslavement of the peasants. Naturally, this process was facilitated by the strengthening of the state apparatus and the creation of special bodies to combat fugitive peasants. The Code of Law of 1550 repeated the articles of the Code of Law of 1497 about "St. George's Day", but at the same time increased the exit fee charged to the peasants. Since 1581, reserved summers are introduced, which canceled the provision on "St. George's Day". Since 1597, a decree on "class years" began to operate, according to which a five-year prescription for the search for fugitives was established. In 1607, the "regular summer" was increased to 15 years. The cathedral code of 1649 recorded the completion of the process of complete and final enslavement of the peasants and abolished the "regular summer". Fugitive peasants were returned regardless of the period that passed after their departure from the owner, along with the whole family and all property. Article I, ch. XI Cathedral Code gives a complete list of all categories of the peasant population. During this period of time, the final consolidation of the proprietary and black-grained peasants took place. After the publication of the Decree on reserved years, a census was made. In the Code of 1649, Articles 9 and 10 of Chapter XI prohibited the adoption from the moment of the publication of the Code of "runaway peasants, brothels and their children and brothers and nephews." The Code of 1649 established the enslavement of all peasants (old-timers and non-residents) and their family members, while canceling the so-called "class years".

Serfdom for the peasants was finally sanctioned by law. The landowners acquired the right to unlimited sale, their exchange, exploitation, the right to dispose of the marital fate of the peasants. Already by the Decree of 1623, in cases of non-payment by landowners and patrimonials of claims on claims, it was allowed to collect them from slaves and peasants.

There have been changes in the position of the black-grained peasants. Their number decreased due to the distribution of rural municipality lands to estates and estates. For admission to the draft community, the conclusion of special contract records was required. By 1678, the correspondence of the courtyards was completed, which served as the basis for replacing the local taxation with the courtyards.

Let's analyze the situation of slaves. During this period of time, there were two categories of slaves: full and bonded. Full or full slaves were at the unlimited disposal of the master. There were other slaves: reports, dowries, spiritual, depending on the source of servitude.

There was a decrease in the sources of servitude. Only the following sources of servitude remained: the birth of slaves from parents and marriage with slaves. The slaves did not have any personal and property rights. But in fact, slaves began to acquire a certain degree of law and legal capacity. Civil deals made with slaves by their own masters became possible. There was a tendency for the transformation of slaves into serfs. The cathedral code legalized the cruel forms of dependence of slaves on their masters, establishing full ownership of slaves. The Code includes marriage, birth, bondage work for a period of more than three months to the sources of servitude.

Centralization of the state. Let's move on to the next question. There is a process of formation of a centralized state. Under Ivan IV, the last inheritance was destroyed. As the Russian state turned into a multinational state, many states were placed in vassal relations with it. The vassals were: Siberian khans, Circassian princes, shakhmal (rulers of the Kumyks), Kalmyk tayshes, Nogai murzas. Vassal relations of some states were nominal. At the end of the 16th century, a tendency towards the complete inclusion (incorporation) of vassal states into the Russian kingdom developed. The king was at the head of the state. The change in the title of head of state in 1547 was an important political reform. In the XVII century. all state affairs were carried out on behalf of the king.

The role of royal power. The Cathedral Code included a chapter:

"On the state honor, and how to protect its state health." This chapter proclaimed:

confirmation of the role of the king in the political life of the country;

the principle of primogeniture and one inheritance.

The recognition of the tsar by the Zemsky Sobor was considered one of the conditions for the recognition of the legality of the royal power. One of the most important acts was the royal wedding. A special rite, the so-called chrismation, would have been added to the royal wedding ceremony in the 17th century.

The royal throne was usually inherited. At the end of the 15th century, the procedure for electing the tsar at the Zemsky Sobor was established, which was supposed to strengthen the authority of the monarch's power.

The tsar had great rights in the field of legislation, administration, and court. But he ruled not alone, but together with the Boyar Duma, Zemsky Sobor.

The Boyar Duma was a permanent body under the tsar; together with him, it solved the main issues of management and foreign policy. The real significance of the Duma was ambiguous. So, for example, during the years of the oprichnina, her role was small. There were changes in the social composition of the Duma in the direction of strengthening the representation of the nobility. It also did not include representatives of the top of the urban population. Special commissions were formed to prepare cases submitted to the Duma. Under the Duma, a bureaucratic and bureaucratic apparatus was created.

Zemsky Sobors. Zemsky Sobors played an important role in government during the period under study. They represented an estate-representative institution that was not permanently operating, but was assembled as needed. Only in the first decade of the reign of Mikhail Romanov, the Zemsky Sobor acquired the significance of a permanent representative institution. The strengthening of the tsarist power was manifested in the onset of a long break in his activities. Zemsky Sobors consisted of three main parts: the Boyar Duma, the Cathedral of the Higher Clergy (the Consecrated Cathedral) and. meetings of representatives from people of all ranks, i.e. local nobility and merchants. At the beginning, for example, when the Council of 1566 was convened, the representation was organized not by election, but by trust in the representatives of the "government". The right to convene the Zemsky Sobor belonged to the tsar or the authority replacing him, i.e. Boyar Duma, patriarch, provisional government. Sometimes the initiative to convene a Council came from the Council itself. The meeting of the Council usually began with its solemn opening, where the tsar himself or on behalf of the tsar read his speech, which explained the reason for convening the Council and formulated the issues that were to be resolved. After the opening of the Zemsky Sobor, it began to discuss issues, for which it was divided into its component parts: the Boyar Duma, the Sacred Cathedral, Moscow noblemen, archers. City nobles and townspeople were still divided into "articles". Each part of the Council decided the issue separately and formulated the decision in writing. These decisions were brought together at the second general meeting. Usually, however, these decisions were the material from which the tsar or the Boyar Duma drew conclusions. They (Councils) were convened to resolve the most important issues: to elect kings, to resolve issues of war and peace, to establish new taxes and taxes, to adopt especially important laws. When discussing these issues, representatives of officials petitioned the government. Zemsky Sobors were the organ of influence of the local nobility and the top of the merchant class.

Features of elections to Zemsky Sobors. The organization of elections to the Zemsky Sobors, the norms of representation from various estates, their number and composition were uncertain. As a rule, the nobles made up the majority of the cathedral. For the noblemen of the capital there were special privileges, they sent two people from all ranks and ranks to the Zemsky Sobor, while the nobles of other cities sent the same amount from the city as a whole. So, for example, out of 192 elected members of the Zemsky Sobor in 1642, 44 were delegated by Moscow nobles. The number of citizens' deputies in the Zemsky Sobor sometimes reached 20. It is necessary to pay attention to the fact that, in fact, Zemsky Sobors limited the power of the tsar to a certain extent, but also strengthened it in every possible way. This is the dialectic of the interaction between the power of the tsar and the Zemsky Sobor.

Order system. Competence. The system of orders as central government bodies continued to develop and strengthen. The final development of the order system takes place in the second half of the 16th century. They arise as needed. Some of the orders are split into a number of departments, which, developing gradually, turn into independent orders. The lack of planning in the organization of orders led to ambiguity in the distribution of competence between them. In the 17th century, the number of orders was constantly changing, reaching 50. The main feature of the order system was the combination of administrative and judicial functions.

There was the following division of orders: palace-patrimonial, military, judicial-administrative, regional (central-regional), in charge of special branches of government.

Palace financial orders: hunter, falconer (in charge of the royal hunt), equestrian, order of the large palace, order of the large treasury (in charge of direct taxes), order of the large parish (in charge of indirect taxes, a new quarter (in charge of drinking income).

Military orders: category (in charge of all military administration, and the appointment of service people to the post), streltsy, Cossack, foreign, weapons, armor, pushkarsky.

Judicial-administrative group: local order (in charge of the distribution of estates and estates, and which was a judicial place for land affairs), lackeys (in charge of securing and releasing slaves, accusation of robbery), zemstvo order (court and management of the draft population of Moscow).

Regional orders: central government bodies in charge of the so-called quarters or chets: Nizhegorodskaya (Nizhniy uyezd, Novgorod, Perm, Pskov), Ustyuzhskaya, Kosgromskaya, Galitskaya, Vladimirskaya.

The regional ones include 4 court orders: Moskovsky, Volodimirsky, Dmitrovsky, Ryazansky. And then: Smolensk, Order of the Kazan hut, Siberian, Malorosky.

Orders in charge of special branches of management: ambassadorial (foreign affairs, non-serving foreigners, post office), stone order of book printing), pharmacy order, printed, (certifying government acts by attaching a seal to them), monastery order (organized for the trial of church authorities), order of gold and silver business.

Orders were created as needed, often without a precise definition of their competence, the order of their organization and activities. All this led to red tape and duplication, bureaucracy. The orders included embezzlement and bribery.

It is known that the changes taking place in the development of the state affected the local government. The main administrative unit was the county. It was uneven. The county was divided into camps, and camps into parishes. Judicial districts - lips were organized within the district; rank - military district.

Lip self-government. In 1556, the feeding system was abolished and replaced with a system of labial and zemstvo self-government. Lip self-government began to be created over time in each county. The lip hut, consisting of a laborer, kissing people, and a lip clerk, was the organ of lip self-government. - landowners: lip elders were necessarily chosen from the nobility or children of the boyars. Peasants were also assistants to the elders (kissing people). Lip self-government was introduced in those counties where landlordism was highly developed, and in areas where trade and craft economy was highly developed, land tenure was introduced Zemstvo institutions developed later than labial ones. They were introduced in uyezds, in groups of volosts, in individual volosts. The competence of zemstvo institutions extended to all branches of administration and courts. In some uyezds, zemstvo institutions operated simultaneously with labial institutions.

At the same time, the voivodship-order administration was introduced (the competence of the voivode grew). The dispatch of voivods to border areas took place at the beginning of the 17th century, the introduction of a voivodship-order administration meant the further development of the bureaucratic system. The governors were appointed by the tsar and the Boyar Duma for a year or two. Several voivods were sent to large districts, one of whom was in charge, others were considered his comrades. Clerks or clerks with an "assignment" were appointed as his closest assistants. The office of the voivode was located in the clerk hut, the functions of the voivode, determined by special instructions or orders, were varied. The governors were in charge of the police, military affairs, had the right to court, sometimes they were instructed (in the border districts) to even be in charge of relations with foreign states. At first, the governors did not interfere in the lip self-government. But over time, the power of the voivods increased, and their interference in the province and zemstvo self-government became significant. The governors subjugated the labial institutions and made labial wardens and kissers their assistants. The governors received a salary. They were forbidden to take feed from the inhabitants. And it was also forbidden to force residents to do anything for themselves. According to the Cathedral Code, the voivods were forbidden to enter into obligatory relations with local people. At the end of the 17th century, in some outskirts, the largest military-administrative districts, the so-called ranks, were created, which concentrated all the management of the industry.

Fiscal policy. During the period under study, the reform of the financial system continued. To determine the amount of taxes, the government carried out a widespread description of the land. Scribe books were compiled, which determined the number of salary units (the so-called sok). The "plow" included a different amount of land - depending on its quality. In the 17th century, additional direct and indirect taxes were introduced: customs, salt, tavern (or drinking), the so-called "pyatina" - the collection of one fifth of the value of movable property.

These are the general features of the state and social structure of the country at a given time. The period under study is characterized by a very intensive development of law, an increase in the role of tsarist legislation.

Sources of law. Codification. Among the monuments of law, laborer and zemstvo charter letters are distinguished, in which the principles of labial and zemstvo self-government, customs documents are established. Codification during this period began with the publication of the Code of Law of 1550 (Tsarist or Second). In the 1550 Code of Laws, the range of issues regulated by the central government was expanded, and the features of the search process were strengthened. Regulation permeates the spheres of criminal law and property relations. There is a strengthening of the class principle and the circle of subjects of crime is expanding. The main source of this code of law was the Code of Law of Vasily III that has not come down to us. During the codification, new decree material was involved, as well as labial and zemstvo charter letters. The Code of Law was divided into 100 articles, arranged according to some (rather elementary) system. All legislative material of the Code of Law can be divided into four parts:

The first contains decisions related to the central court;

the second - to the regional court;

the third - to civil law and procedure;

The fourth one contains additional articles.

The Code of Law is a collection of judicial law, and. in general, reflected the interests of the local nobility and merchants.

Almost simultaneously with the Code of Laws, Stoglav was published (in 1551), which was the result of the legislative activity of the church (hundred-headed) cathedral. Stoglav - 100 chapters (articles), contains, along with important decrees on the church, a number of norms of criminal and civil law that provide enhanced protection of the interests of the clergy. When drawing up the Code of Laws, it was envisaged to replenish it with new legislative material, which could appear in the form of separate decrees and boyar sentences. Therefore, Article 98 of the Code of Law establishes the procedure for attaching "new cases" to its rulings - additional decrees. These postscripts were made with each order. Over time, the so-called Ordinary Books of Orders were drawn up. Among them, the Decree books of court cases, Zemsky Prikaz, and Rogue Prikaz are of great importance in the history of law. In them, the interests of the local nobility were defended to an even greater degree. Both the Tsar's Law Code and individual decrees issued after it largely regulate the relations that are characteristic of the process of enslaving the peasants.

The most important monument of this time is the Cathedral Code of 1649, a code that to a large extent determined the legal system of the Russian state for many years. To draw up the code, the government created a special commission chaired by Prince Odoevsky. The draft developed by this commission was submitted for consideration to the Zemsky Sobor and discussed at joint meetings of the commission with the elected members of the Zemsky Sobor for over 5 months. Members of the commission submitted petitions to the tsar with a request to issue new laws on various issues. After the discussion of the Project was over, it was approved in 1649 by the Zemsky Sobor. The codified laws were called the Cathedral Code.

The sources of the code were: judicial codes, decrees and boyar sentences, the city laws of the Greek kings, i.e. Byzantine law, Lithuanian status, new articles, both included by the drafters themselves, and introduced at the insistence of the elected members of the Council - according to their petition. Among these articles, it is necessary to point out the eye of the XI - "Court of the peasants", in which the "fixed summers" were canceled and in which the landowner's full right to work and the personality of the peasant was affirmed. The cathedral code was a code in which the principles of Russian law were developed, expressed in the "Russian Pravda" "and in the law codes. The cathedral code was in the interests of the nobility. It was a code of serfdom. It should be noted that from a technical and legal point of view, the Code, as a code was a step forward compared to the Code of Law.

Further development of legislation was carried out through the issuance of decrees. Decrees canceling, supplementing or amending the resolutions of the Cathedral Code were named after the said articles. The characteristics of the sources allows us to draw a conclusion about the intensive development of law in the period under study. Let us turn to the analysis of the branches of law.

Features of land use. The Cathedral Code defined in detail the existing forms of feudal land tenure. Special Chapter 16 summarized all the major changes in the legal status of local land tenure. The Cathedral Code stipulated that both boyars and nobles could be the owners of estates; the estate was passed on to the sons by inheritance in a certain order; part of the land after the death of the owner, is received by his wife and daughters; the estate could be given to the daughter as a dowry, and, in addition, the exchange of an estate for an estate and a patrimony was allowed. But the landowners did not receive the right to freely sell land (only by tsarist decree), they did not have the right to mortgage the land. But at the same time, one cannot ignore the fact that article 3 of the chapter of the Cathedral Code allowed the exchange of a large estate for a smaller one and, thus, under the cover of exchange, sell the estate. The patrimony, in accordance with the Cathedral Code, still provided privileged land tenure. The patrimony could be sold (with obligatory registration in the local order), mortgaged and inherited. The Cathedral Code contains a provision on the right of patrimonial redemption - a period of 40 years for the redemption of a sold, exchanged, mortgaged patrimony. The circle of relatives who had the right to ransom was also determined. The right of generic redemption did not extend to the ransomed estates. According to the law, it was only possible to sell estates to feudal lords who lived in the same district. Purchased estates were called land holdings acquired by someone from members of a kind, the possession of them also entailed the duty of service. Refusal to serve was the result of the removal of estates from their owners and their inclusion in the tsarist domain. The favored estates were called estates that were granted by the king. They were characterized by a great limited rights by the owners, they were selected if they did not please the king, sometimes it was a limited lifetime possession. At the end of the 17th century, estates became the dominant type of property. Only service people could own estates: boyars, nobles, boyar children, clerks, etc. The size of the estate depended on the quality of the land. The estates were given to the children of residential people upon reaching the age of 15. As a rule, the estates included lands inhabited by peasants, but in addition to this, vacant lands, hunting and fishing grounds were allocated. Peasants, when assigning land to landowners, received a so-called obedient letter, according to which they were instructed to obey the owner. In addition, courtyards and garden lands were assigned to landowners in cities. The main duty of the landlords was to carry out service.

Land inheritance. Gradually, the nobility acquired the right to inherit estates. In the first quarter of the 17th century, the inheritance of estates was already mentioned in special decrees. In 1611, the principle was established that the estates could remain with widows and children. From the father's estates, allotments were allocated to sons according to their official position, and to daughters and widows for subsistence. The rest of the estate was passed on to side relatives. In 1684, a law was passed, according to which the children received the entire estate of their father. From the end of the 16th century, donation of estates to the benefit of monasteries was allowed. Church domains were recognized as inalienable.

The pledge law also developed. The following forms of collateral were used: the mortgaged land was transferred to the mortgagee, as well as when the creditor received the right to temporarily use the mortgaged land, and this use replaced the payment of taxes. The Cathedral Code determined the rights to someone else's property, i.e. easements: the right to leave dams on the river within the limits of their possession, the right to mow, fish, hunt in forests, on lands belonging to another owner. In the cities, it was forbidden to build stoves, cooks close to neighboring buildings, it was not allowed to pour water, sweep away dirt on neighboring yards. The Code provided for the right of passers-by, as well as those driving the cattle, to stop in the meadows that adjoined the road.

The law of obligations also received its further development. Obligations arising from contracts are secured not by the person of the defendant, but by his property. Moreover, the responsibility was not individual, but collective: spouses, parents, children were responsible for each other. Debts on obligations were inherited. Much attention was paid to the forms of concluding contracts. The written form of the contract became more and more important. And when registering merchants for land or courtyards, registration of the document at the institution was required. A deed of sale (a deed of sale) is an act of acquisition of property. The procedure for recognizing the contract as invalid was determined if it was concluded in a state of intoxication, with the use of violence or by deception. There are also known contracts of purchase and sale, exchange, donation, storage, luggage, rental of property.

Succession law has also evolved. There is a distinction between inheritance by law and by will. Particular attention was paid to the order of inheritance of land. The will was drawn up in writing and signed by the testator, and in case of his illiteracy - by witnesses and confirmed by the church authorities. The possibilities of the will were limited by class principles: it was impossible to bequeath land to churches and monasteries; ancestral and granted estates, as well as estates were not subject to testamentary disposition. The patrimonial and granted estates were subject to inheritance only to members of the same clan to which the testator belonged. Daughters inherited in the absence of sons. Widows received part of the fiefdom they had served "for their living", that is, in life possession, in the event that there were no estates left after the death of the spouse. The estates were inherited by their sons. The widow and daughters received part of the estate for subsistence.

Family law. Only marriage contracted in the church was recognized as law. It was concluded with the consent of the parents. And for the marriage of serfs, the consent of the landowners was necessary. The marriageable age for men is set at 15 years, and for women - 12 years. In the family there was paternal authority, as well as the authority of the husband over his wife.

Crimes. A crime was understood as a violation of the royal will and law. Representatives of estates were recognized as subjects of crimes. Crimes were distinguished between intentional and reckless. For accidental acts, no punishment was established. But the law does not always distinguish between an accidental, unpunished action and a careless form of guilt. The Code refers to the institute of necessary defense, but the limits of necessary defense (excessive defense and degree of danger) were not established.

Cover-ups, relapse. In the Cathedral Code, complicity, incitement, aiding, and concealment are regulated in more detail. Relapse was punished more severely. In the Cathedral Code, the types of crimes are set out according to a certain system. It highlighted a crime against faith, then state crimes (crimes against the foundations of faith, royal power and personally against the king: insulting the monarch, causing harm to his health). Responsibility was established even for naked intent and negligence. The law said a lot about such crimes as treason, conspiracy, riot. The characteristics of crimes against the order of government, military crimes, crimes against the judiciary are given. The Cathedral Code regulates crimes against the person. These include: murder, bodily harm, insult in word and deed. Among property crimes stood out: theft, robbery, robbery. Crimes against morality stood out: procuring, violation of family charters. It should be noted that in the Code the corpus delicti were formulated more clearly than before.

Punishments. In the Code, the frightening nature of punishments is further enhanced. The following were used: the death penalty - simple and qualified; corporal punishment - whipping, flogging, branding, imprisonment, exile to the outskirts of the country, hard labor; deprivation of rank, resignation from office, church repentance. The use of the death penalty and corporal punishment was carried out in public. The Cathedral Code was characterized by a plurality of punishments and a difference in punishments depending on social belonging.

The Cathedral Code provided for two forms of the process and the court. The inquisition process became more widespread. It was practically used in all criminal cases. The most brutal trial was in cases involving crimes against the king and the state. The Cathedral Code also speaks in detail about the accusatory adversarial process. It was carried out in the consideration of property disputes and small criminal cases. Chapter 10 of the Cathedral Code speaks about the system of testimony. The so-called "general search" and "general search" were used as evidence. The difference between these two types was that in a "general search" - a survey of the entire population on the facts of the commission of a crime, and "general" - a survey of a specific person suspected of committing a crime. These are some of the main features of the development of law.

The history of the studied period was interesting, multifaceted, tragic. In Russia, the remnants of feudal fragmentation were finally eliminated, and the country's economic and political unity was formed. A class-representative monarchy emerged. It should be noted that the strengthening of state power led to a decrease in the importance of estate-representative institutions.

History of the state and law of foreign countries. Part 1 Krasheninnikova Nina Alexandrovna

§ 2. Estates-representative monarchy

Changes in the legal status of estates in the XIV-XV centuries. Further growth of cities and commodity production entailed not only an increase in the number and political activity of the urban population. It caused the restructuring of the traditional feudal economy, forms of exploitation of the peasantry. Under the influence of commodity-money relations, significant changes took place in the legal status of the peasants. By the XIV century. in most of France the servage disappears. The bulk of the peasantry is personally free censors, obliged to pay the lord a monetary rent (qualification), the amount of which increased.

The intensification of feudal exploitation, as well as the economic difficulties associated with the Hundred Years War with England, caused an aggravation of the internal political struggle. This was reflected in a number of urban uprisings (especially in Paris in 1356-1358) and peasant wars (Jacqueria in 1358). There were also changes in the struggle among the feudal lords themselves, which was associated with the strengthening of royal power and its clash in the process of uniting the country with the feudal oligarchy. During the Hundred Years War, there were many confiscations of the lands of large feudal lords, who betrayed the French king. These lands were distributed to small and middle nobles who actively supported the royal power.

In the XIV-XV centuries. in France, the restructuring of the estate system was completed, which was expressed in the internal consolidation of the estates. The design of the three large estates did not mean the disappearance of the hierarchical structure of the feudal class inherited from the previous period. However, for the sake of strengthening their common positions, the feudal lords were forced to give up their former independence, abandon some of the traditional seignorial privileges. The consolidation of the estate system meant a gradual end to the destructive internecine feudal wars and the establishment of new mechanisms for settling intra-class conflicts.

The first estate in France was considered clergy. The unification of all the clergy into a single estate was the result of the fact that the royal power by the XIV century. won a crucial victory in the fight against the papacy. It was recognized that the French clergy should live according to the laws of the kingdom and be considered an integral part of the French nation. At the same time, some church prerogatives were limited, which hindered the political unification of the country and the recognition of the supremacy of royal power, the circle of persons falling under church jurisdiction was reduced.

With the establishment of a single legal status for the clergy, their most important estate privileges were strengthened. The clergy, as before, had the right to receive tithes and various donations, retained their tax and judicial immunity. It was exempted from any government services and duties. The latter did not exclude the fact that certain representatives of the clergy were involved by the king in solving important political issues, acted as his closest advisers, and occupied high posts in the state administration.

The second estate in the state was nobility, although in fact in the XIV-XV centuries. it played a leading role in the social and political life of France. This estate united all the secular feudal lords, who were now considered not just as vassals of the king, but as his servants. The nobility was a closed and hereditary (in contrast to the clergy) class. Initially, access to the estate of the nobility was open to the elite of the townspeople and wealthy peasants, who, having become rich, bought land from the ruined nobles. The tribal nobility, striving to preserve the spirit of the feudal caste, achieved that the purchase of estates by persons of ignoble origin ceased to give them titles of nobility.

The most important privilege of the nobility remained its exclusive ownership of land with the inheritance of all real estate and rental rights. Nobles had the right to titles, coats of arms and other signs of noble dignity, to special judicial privileges. They were exempted from paying state taxes. In fact, the only duty of the nobility is to perform military service to the king, and not to a private lord, as it was before.

The nobility was still patchy. The titled nobility - dukes, marquises, earls, viscounts and others - claimed high posts in the army and in the state apparatus. The bulk of the nobility, especially the lower ones, had to be content with a much more modest position. Its well-being was directly related to the increased exploitation of the peasants. Therefore, the small and middle nobility vigorously supported the royal power, seeing in it main forcecapable of keeping the peasant masses in check.

In the XIV-XV centuries. basically completed the formation and "third estate" (tiers etat), which was replenished by the rapidly growing urban population and the increase in the number of peasant censors. This class was very variegated in composition and practically united the working population and the emerging bourgeoisie. Members of this class were viewed as "ignoble" and did not have any special personal or property rights. They were not protected from arbitrariness on the part of the royal administration and even individual feudal lords. The Third Estate was the only taxable estate in France, and the entire burden of paying state taxes fell on it.

The organization of the third estate itself was of a feudal-corporate nature. It acted primarily as a set of urban associations. At this time, the idea of \u200b\u200bequality and universality of interests of members of the third estate had not yet emerged, it did not realize itself as a single national force.

Establishment of an estate-representative monarchy. At the beginning of the XIV century. in France, the seignorial monarchy is replaced by a new form of the feudal state - estate-representative monarchy. The formation of the estate-representative monarchy here is inextricably linked with the progressive process of political centralization for this period (by the beginning of the XIV century, 3/4 of the country's territory was united), the further rise of royal power, the elimination of the autocracy of individual feudal lords.

The senior power of the feudal lords essentially lost its independent political character. The kings deprived them of the right to collect taxes for political purposes. In the XIV century. it was established that the consent of the royal authority was necessary for the collection of the seigneurial tax (talya). In the XV century. Charles VII canceled the collection of talha by individual large lords altogether. The king forbade the feudal lords to establish new indirect taxes, which gradually led to their complete disappearance. Louis XI took away the right to mint coins from the feudal lords. In the XV century. in circulation in France there was only a single royal coin.

Kings also deprived feudal lords of their traditional privilege of waging private wars. Only a few large feudal lords retained in the 15th century. their independent armies, which gave them some political autonomy (Burgundy, Brittany, Armagnac).

The seigneurial legislation gradually disappeared, and also through the expansion of the range of cases that constituted the "royal cases", seigniorial jurisdiction was significantly limited. In the XIV century. the possibility of appeal against any decision of the courts of individual feudal lords to the Paris Parliament was provided. This finally destroyed the principle according to which the seigneurial justice was considered sovereign.

In the path of the French kings, who sought to unify the country and to strengthen their personal power, for several centuries there was another serious political obstacle - the Roman Catholic Church. The French crown never agreed with the claims of the papacy to world domination, but, not feeling the necessary political support, avoided open confrontation. This situation could not persist indefinitely, and by the end of the XIII - the beginning of the XIV century. the strengthened royal power became more and more incompatible with the policy of the Roman curia. King Philip the Fair challenged Pope Boniface VIII, demanding subsidies from the French clergy to wage war with Flanders and extending royal jurisdiction to all the privileges of the clergy. In retaliation, the pope issued a bull in 1301, in which he threatened the king with excommunication. This conflict ended with the victory of the secular (royal) power over the spiritual and the transfer, under pressure from the French kings, of the residence of the popes in Avignon (1309-1377) - the so-called "Avignon captivity of the popes".

The victory of the French crown over the Roman papacy, the gradual elimination of the independent rights of feudal lords was accompanied in the XIV-XV centuries. a steady increase in the authority and political weight of the royal power. Legists played an important role in the legal substantiation of this process. The Legists defended the priority of secular power over ecclesiastical power, denied the divine origin of royal power in France: "The king received the kingdom from no one else but from himself, and with the help of his sword."

In 1303, the formula was put forward: "the king is the emperor in his kingdom." She emphasized the complete independence of the French king in international relations, including from the German-Roman emperor. The French king, according to the legists, had all the prerogatives of the Roman emperor.

With reference to the well-known principle of Roman law, the legists argued that the king himself is the supreme law, and therefore can create legislation at his own will. To pass laws, the king no longer required the convocation of vassals or the consent of the royal curia. The thesis was also put forward: "all justice flows from the king", according to which the king received the right to consider any legal case himself or delegate this right to his servants.

The estate-representative monarchy was established at a certain stage of centralization of the country, when the autonomous rights of feudal lords, the Catholic Church, city corporations, etc. were not fully overcome. Solving important national tasks and taking on a number of new state functions, the royal power gradually broke political a structure characteristic of the seigneurial monarchy. But in the implementation of its policy, it faced a powerful opposition of the feudal oligarchy, the resistance of which could not be overcome only by its own means. Therefore, the political power of the king largely stemmed from the support he received from the feudal estates.

It was by the beginning of the XIV century. finally, built on a political compromise, and therefore not always a strong alliance of the king and representatives of different estates, including the third estate, is finally formed. The political expression of this union, in which each of the parties had its own specific interests, became special estate-representative institutions - the States General and the provincial states.

States General. The emergence of the States General marked the beginning of a change in the form of the state in France - its transformation into an estate-representative monarchy.

The emergence of the States-General as a special state body was preceded by expanded meetings of the royal curia (councils, etc.), which took place as early as the XII-XIII centuries. The convocation of the States General by King Philip IV the Beautiful in 1302 (the very name "Etats generaux" was used later - from 1484) had quite specific historical reasons: the unsuccessful war in Flanders, serious economic difficulties, the dispute between the king and the Pope. But the creation of a nationwide estate-representative institution was also a manifestation of an objective law in the development of the monarchical state in France.

The frequency of convening the States General has not been established. This question was decided by the king himself, depending on the circumstances and political considerations. Each convocation of the states was individual and determined solely by the discretion of the king. Higher clergy (archbishops, bishops, abbots), as well as major secular feudal lords were invited personally. The states-general of the first convocations did not have elected representatives from the nobility. Later, the practice was approved, according to which the middle and small nobility elects their deputies. Elections were also held on behalf of churches, convents of monasteries and cities (2-3 deputies each). But the townspeople and especially the legists were sometimes elected from the estates of the clergy and nobility. About 1/7 of the States General were lawyers. The deputies from the cities represented their patrician-burgher elite. Thus, the Estates General has always been the body representing the wealthy strata of French society.

The questions submitted to the States General and the duration of their meetings were also determined by the king. The king resorted to convening the States General in order to get the support of the estates for various reasons: the fight against the Knights Templar (1308), the conclusion of a treaty with England (1359), religious wars (1560, 1576, 1588), etc. The King sought the opinion of the States General on a number of bills, although formally, their consent to the passage of royal laws was not required. But most often the reason for the convening of the States General was the king's need for money, and he turned to the estates with a request for financial assistance or permission for another tax, which could only be collected within one year. It was only in 1439 that Charles VII obtained consent to levy a permanent royal talha. But if it was a question of establishing any additional taxes, then, as before, the consent of the States General was required.

The states-general turned to the king with requests, complaints, protests. They had the right to make proposals and criticize the activities of the royal administration. But since there was a certain connection between the requests of the estates and their voting on the subsidies requested by the king, the latter in some cases yielded to the States General and issued the corresponding ordinance at their request.

The states-general as a whole were not a simple instrument of the royal nobility, although objectively they helped her to strengthen and strengthen her position in the state. In a number of cases, they opposed the king, evading decisions that were pleasing to him. When the estates showed intransigence, the kings did not collect them for a long time (for example, from 1468 to 1484). After 1484, the States-General practically ceased to meet at all (until 1560).

The most acute conflict between the States General and the royal power occurred in 1357 at the time of the uprising of the townspeople in Paris and the capture of King John of France by the British. The states-general, in which mainly representatives of the third estate took part, put forward a reform program called Great March Ordinance. In return for granting subsidies to the royal power, they demanded that the collection and expenditure of funds be made by the States General themselves, which were to be collected three times a year, and without being convened by the king. "General reformers" were elected, who were empowered to control the activities of the royal administration, to dismiss individual officials and punish them, up to and including the death penalty. However, the attempt by the States General to secure permanent financial, control, and even legislative powers was not successful. After the suppression of the Paris uprising and Jacquerie in 1358, the royal authorities rejected the demands contained in the Great March Ordinance.

In the States General, each estate met and discussed issues separately. Only in 1468 and 1484. all three estates met together. Voting was usually organized according to balajas and seneschalties, where deputies were elected. If differences were found in the position of the estates, voting was carried out by estates. In this case, each estate had one vote, and in general the feudal lords always had an advantage over the third estate.

The deputies elected to the States General were endowed with an imperative mandate. Their position on issues brought up for discussion, including voting, was bound by the instructions of the voters. After returning from the meeting, the deputy had to report to the voters.

In a number of regions of France (Provence, Flanders) from the end of the XIII century. local estate-representative institutions appeared. At first they were called "council", "parliament" or simply "people of three estates". By the middle of the 15th century. began to use the terms "states of Burgundy", "states of the Dauphin", etc. The name "provincial states" was fixed only in the 16th century. By the end of the XIV century. there were 20 local states, in the XV century. they were present in almost every province. In the provincial states, as well as in the States General, peasants were not allowed. Often, kings opposed individual provincial states, since they were strongly influenced by local feudal lords (in Normandy, Languedoc), and pursued a policy of separatism.

Central and local government. The emergence of the estate-representative monarchy and the gradual concentration of political power in the hands of the king did not immediately entail the creation of a new apparatus of state administration.

The central management bodies have not undergone significant reorganization. At the same time, an important principle is affirmed that the king is not bound by the opinion of his advisers, but, on the contrary, all administrative and other power powers of government officials derive from the king. Of the former positions, which have now become court titles, only the position of the chancellor, who became the king's closest aide, has retained its significance. Chancellor, as before, he was the head of the royal chancellery, he now drew up numerous royal acts, appointed to judicial positions, presided over the royal curia and in the council in the absence of the king.

The further development of centralization was manifested in the fact that an important place in the system of central government was occupied by the established on the basis of the royal curia Great advice (from 1314 to 1497). This council included the legists, as well as 24 representatives of the highest secular and spiritual nobility (princes, peers of France, archbishops, etc.). The Council met once a month, but its powers were of an exclusively deliberative nature. As the royal power strengthens, its importance decreases, the king often resorts to convening a narrow, secret council, consisting of persons invited at his discretion.

There are also new positions in the central royal apparatus, selected from the legists and noblemen loyal to the king - clerks, secretaries, notaries, etc. These positions did not always have clearly defined functions, were not organizationally consolidated into a single administrative apparatus.

Prevost and Bailly, which were previously the main bodies of local administration, in the XIV century. lose a number of their functions, in particular the military. This is due to the fall in the importance of the feudal militia. Many of the court cases previously handled by the bailies go to their appointed lieutenants. From the end of the 15th century. kings directly appoint in balaages lieutenants, and the bailiffs turn into an intermediate and weak administrative link.

In an effort to centralize local government, kings introduce new positions governors. In some cases, governors who received the rank of royal lieutenant had purely military functions. In other cases, they were appointed to the bailiage, replacing bailies and receiving broader powers: to prohibit the construction of new castles, to prevent private wars, etc.

In the XIV century. officials such as lieutenant generals, usually appointed from princes of blood and nobility. At first, this position was established for a short period and with narrow powers: exemption from certain taxes, pardon, etc. In the 15th century. the number of lieutenant generals has increased and the terms of their activities have increased. Usually they ruled over a group of balyazhes or an administrative district, which at the end of the 15th century. began to be called a province.

Local centralization has also affected urban life. Kings often deprived cities of the status of communes, changed previously issued charters, and limited the rights of citizens. The royal administration begins to control the elections of the city administration, selecting suitable candidates. A system of administrative trusteeship was established over the cities. Although in the XV century. communes in some cities were restored, they were fully integrated into the royal administration. The city aristocracy continued to enjoy limited self-government, but all important city council meetings were usually chaired by a royal official.

Organization of financial management. The lack of a stable financial base for a long time affected general position royal power, especially since the Hundred Years War demanded huge expenses. At first, income from the domain and from the minting of coins remained an important source of funds for the state treasury, and kings, in an effort to strengthen their financial position, often issued defective money. However, the collection of royal taxes is gradually becoming the main source of replenishment of the treasury. In 1369, the constant collection of customs duties and salt tax was legalized. Since 1439, when the States General authorized the levy of a permanent king's talha, the king's financial position had been substantially strengthened. The size of the tally increased steadily. Thus, under Louis XI (1461-1483), it tripled.

In the same period, specialized financial management bodies appear. At the beginning of the XIV century. a royal treasury was created, and then a special accounting chamber, which advised the king on financial matters, checked the revenues from the bailly, etc. Under Charles VII, France was divided into generalities (generalites) for fiscal purposes. The generals placed at their head had a number of administrative, but primarily tax functions.

Organization of the Armed Forces. The general restructuring of management also affected the army. The feudal militia continues to survive, but from the XIV century. the king demands direct military service from all the nobility. In 1314, major lords challenged this order, but during the Hundred Years War it was finally established.

Gradually, the main goal of royal power was achieved - the creation of an independent armed force, which is a reliable instrument of centralized state policy. Strengthening the king's financial base allowed him to create a mercenary armed force (from Germans, Scots, etc.), organized into shock troops. In 1445, having been able to levy a permanent tax, Charles VII organized a regular royal army with a centralized leadership and a clear system. Permanent garrisons were also stationed throughout the kingdom to prevent the re-emergence of feudal unrest.

The judicial system. The royal administration pursued a policy of unification in court proceedings, somewhat limiting ecclesiastical and displacing seignorial jurisdiction. The judicial system was still extremely confused, the court was not separated from the administration.

Small court cases were decided by the provost, but cases of serious crimes (the so-called royal cases) were considered in the court of the bali, and in the 15th century. - in court chaired by a lieutenant. The local nobility, the royal attorney, took part in the court of the bailly. Since the provosts, bailies, and later lieutenants were appointed and dismissed at the discretion of the king, all judicial activities were completely controlled by the king and his administration. The role of the Paris Parliament has grown, and since 1467 its members have been appointed not for one year, as before, but for life. Parliament became the highest court for the feudal nobility, became the most important court of appeal in all court cases. Along with the implementation of purely judicial functions, the parliament in the first half of the XIV century. acquires the right to register royal ordinances and other royal documents. Since 1350, the registration of legislative acts in the Paris Parliament becomes mandatory. The lower courts and parliaments of other cities, when making their decisions, could only use registered royal ordinances. If the Paris Parliament found inaccuracies or deviations from the "laws of the kingdom" in the registered act, it could declare renovation (objection) and refuse to register such an act. The renovation was overcome only through the personal presence of the king at a meeting of parliament. At the end of the 15th century. Parliament has repeatedly used its right to remonstrate, which increased its authority among other state bodies, but ultimately led to a conflict with the royal power.

From the book History of the Middle Ages. Volume 1 [In two volumes. Edited by S. D. Skazkin] the author Skazkin Sergey DanilovichThe folding of the estate-representative monarchy In the XIV-XV centuries. in Hungary, there is a rapid development of mining, in particular, the extraction of precious metals and copper is growing. This was facilitated by the activities of the royal government interested in increasing the income from development

From the book People's Monarchy author Solonevich IvanMONARCHY AND PLAN Modern humanity is sick with planned fever. Everyone is planning something, and nothing comes of it. The Stalinist five-year plans ravaged the country to the core and concentrated in the camps either ten or fifteen million unplanned survivors.